Western novelist Larry McMurtry, who passed away earlier this year, wrote, “nonfiction is a pleasant way to walk, but the novel puts one horseback, and what cowboy, symbolic or real, would walk when he could ride?”

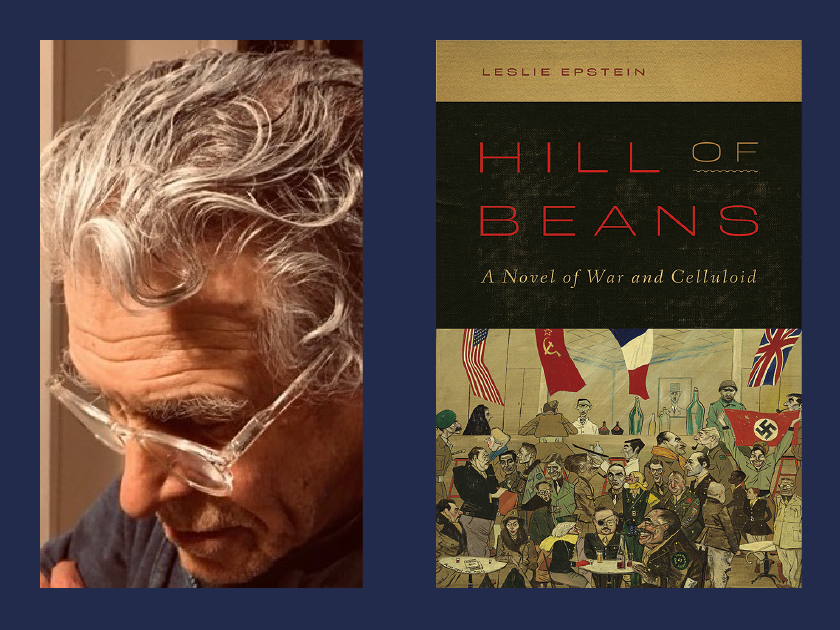

For the past four-and-a-half decades, Leslie Epstein has galloped across the landscape of American fiction. His new novel, Hill of Beans: A Novel of War and Celluloid, marks a return to old stomping grounds, namely the eternally fascinating world of Hollywood. His father and uncle (Philip and Julius Epstein, respectively) and their epic success in writing Casablanca, give rise here to the technicolor story of Jack Warner, with whom they worked and struggled. Like its predecessors, Leslie Epstein’s twelfth book is filled with unique energy and megaphone voice that never stops from first page to last.

Mark Bernheim: More than fifteen years ago, Contemporary Authors (CA) ran a long and insightful piece about you that begins with a quote from Katha Pollitt writing for The New York Times: “If writers got gold stars for the risks they took, Leslie Epstein would get a handful.”

Seeing your work as giant risk-taking is a good way to approach its range and entirety. Can you speak about some risks you have embarked on — what was at stake for you personally and professionally? What books do you think merit a shiny star for intent, and which ones were perhaps less daring? Have your risks been understood?

Leslie Epstein: I never think of myself as taking risks; instead, I am sometimes aware I have no choice. I started King of the Jews four times and each time stopped on the first page. How can I write in this jaunty voice, with these insouciant rhythms, and with the sun as a lemon lozenge when writing about the Holocaust? Cowardice caught me. But after a few days, I realized if I was going to write the book at all, this is how it would come out. It was my own voice I was hearing. Not to make ridiculous comparisons, but I thought of Lear: of how tragedy can be pushed so far — a man jumps from a cliff that is not there and others mock, while he grows into a different man after the fall — that it becomes something like farce.

Often those are the best books, the ones that catch up to the author unaware.

MB: The CA essay quotes you saying: “The entwined (‘twinned’) themes of my work are Jewishness on the one hand, and family, films, and California on the other.” You explain that you turned away from Judaism, away from family, away from California — only to obsessively return to all these in your fiction. Can you set Hill of Beans in this prism?

LE: You answered — or rather, I answered — the question for both of us. Everything worthwhile in art, as Freud and Baudelaire (“genius is nothing more than childhood recaptured at will”) and most artists themselves well knew, comes from childhood. Mine was the film industry and the war and, after the war, the astonishing knowledge of what Hitler did and much of the world allowed him to do: so this is what human beings are, the child as much as told himself. And of course proceeded to forget it.

But we never forget, and so it came out, these themes, entwined, in everything I wrote. To tell you the truth, lots of people are writing about it still — how could they not?— even though they don’t quite know it. Often those are the best books, the ones that catch up to the author unaware. Still, the greatest book since the war, Life and Fate by Vasily Grossman, was written with wide open eyes. But the child is in that book — in the suffering, the muteness, the helplessness, the simple smallness in the midst of clashing forces.

MB: One of your earliest works, and the one that introduced me to your imagination, is Regina, a portrait of New York in the 1970s. It stands almost alone for the depth of its portrayal of American life. Four decades after, if you wanted it to, how would your work involve Americanlife of this millennium? Moreover, your focus has been for the most part on coastal America; how would you characterize American culture away from the coasts, or in addition to them, if you wanted to inform readers what our country is like now?

LE: I thank you for your kindness toward a book I hardly remember. I haven’t reread any of them, except the Leib Goldkorn books, for a laugh now and then and because we are making a new trilorgy (that’s no typo) of the series. I don’t think I’m cut out to write about Middle America, except insofar as all of this country fought in World War II and goes to the movies (making Casablanca the classic it has become). Even after Trump, I write off nobody and nothing, not completely. On the other hand, since you mention the coasts, I do recall the New Yorker map that has the Hudson on one side and the Pacific on the other, and in between a large white swatch labeled “fried food.”

MB: Rarely have I read a more moving statement of affirmation for art than the conclusion to your updated autobiographical statement of 2003: You quote Freud: “What a child has experienced and not understood by the age of two he may never again remember except in his dreams,” and then add, “My books have been such dreams.” You have related this idea to your systematic reading of Proust and your transpositions of his characters to your family members and their embodiments in your works. Now that you present Hollywood again in Hill of Beans, can you elaborate on how a few of these eight-decades-old experiences have taken their place in Epstein-land?

LE: Do you remember that at the end of In Search of Lost Time (Remembrance of Things Past, thank you Scott Moncrief, is the more moving title), Marcel goes to a party and he sees the figures from his childhood transfigured into stooped women trailing their scarves like winding sheets and the men with powdered hair as if they had been wearing the wigs of judges? Well, that happened to me in California, when, burying first my mother and then Uncle Julie within three days of each other, I saw all the glamorous adults of my youth — the actors, writers (even they seemed glamorous to this silly child), directors, the wits and thinkers, and kind people gathered around our pool on sundays. Suddenly they, too, were stooped and gathered at the edge of the palisades that led sharply to the dark, inevitable sea. With a start, I realized that like Marcel, I, too, was growing old (and, see? I have arrived); and like Marcel at that moment, I understood that I had better get down to work.

MB: To close, Tablet magazine recently profiled Herbert Gold on his ninety-seventh birthday through a long conversation with Ray March. It’s narrated that Gold encouraged March to write, urging him, “Tell a sad story of your life and make it funny. Keep running it through the loom…” I found that quotation somehow descriptive of your work. If you agree, can you comment on some of the threads that you have run tirelessly through the loom?

LE: Gee, the warp and woof of a writer’s work are often, as with the case of Gold, best expressed by someone else looking on. I’m impressed with the way you have done it for and about me, Mark. I wonder sometimes about the books I read when I was seven and eight, Paddle to the Sea,The Purple Pirate of Oz, and all of a sudden Grapes of Wrath, with that tortoise single-mindedly trying to cross the highway. Are they not the threads on the loom? Along with my mother for all her pushing and pulling but almost certainly caring, the brother none of us could reach, the sun through the eucalyptus trees and cork trees on our lawn, the cards attached to the rear tires of my bike racing down Amalfi and — well, I am no genius, but look: I was able to recapture a fair amount of those things at will.

Mark Bernheim is an emeritus professor and journalist with degrees in world literature, and the author a biography of Janusz Korczak for young readers. He taught children’s literature at American universities and abroad on Fulbright and other residences in France, Austria, and Italy. He currently freelances as a cultural critic and book editor.