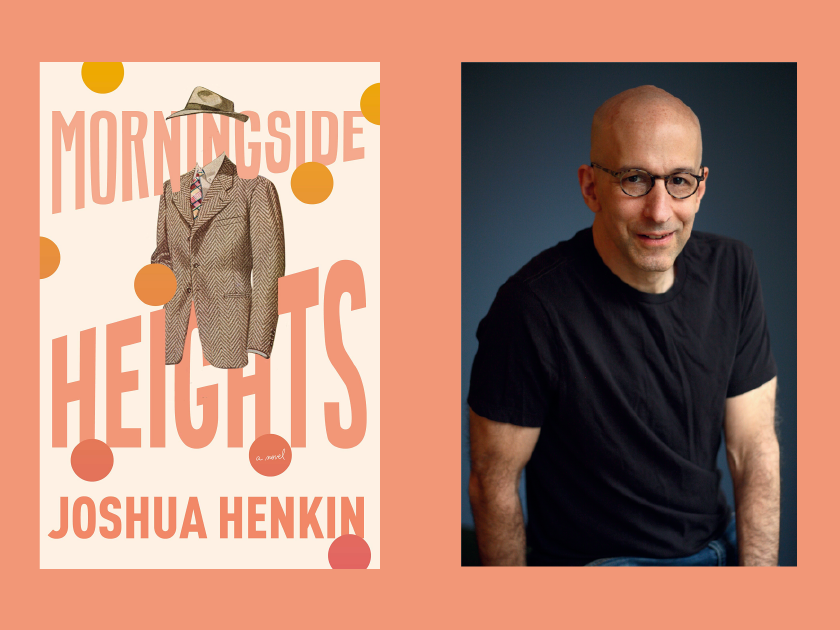

Headshot by Michael Lionstar

Joshua Henkin’s latest novel, Morningside Heights, is a moving look at how families cope with unforeseen events and how relationships evolve through it. Sonia Taitz spoke with Henkin on the inspiration behind the characters, the role of Jewish identity, and the author’s relationship with Morningside Heights.

Sonia Taitz: You often include Jewish elements in your books — sometimes with differing observance levels within families, or in juxtaposition to the non-Jewish world. What is your own Jewish background? What role does being Jewish play in your imagination?

Joshua Henkin: My paternal grandfather was an Orthodox rabbi who lived on the Lower East Side for fifty years and never learned to speak English. My father’s first language was Yiddish. Many years later, when he was clerking for Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, my father used to spend Friday night on the Justice’s couch so he wouldn’t have to travel on Shabbat. My own childhood was sufficiently suffused with Jewish ritual so that when I was six or seven and we were moving the clock forward for Daylight Saving Time, I asked my parents, “Do non-Jews move their clocks forward, too?”

ST: Enid, Professor Robin’s institutionalized sister in Morningside Heights, is portrayed with great compassion. She seems to hold on to aspects of the family legacy that others have forgotten. Can you elaborate on this?

JH: I see Enid as a window onto Spence’s past. In a weird way, Spence is both a genius and a latchkey kid; it’s as if he raised himself. Even before Enid’s accident, Spence was the golden child, and people used to say about him “Enough naches for two.” But beneath Spence’s brilliance, there’s a core vulnerability to him, and you can see that through Enid, through how protective he is of her.

ST: Your knowledge of Morningside Heights as a neighborhood — from the deeply mourned Chock Full O’Nuts on 116th to the Hungarian Pastry Shop — seems real and personally lived. Can you tell us how you know this area, and what it represents to you either personally or thematically?

JH: I don’t believe in themes — themes are for sixth-grade book reports — but I do believe in stories, and in making people and places come to life. I grew up in Morningside Heights. My mother still lives in the neighborhood, as does my brother, and my wife teaches there. I know those streets and establishments as well as I know anything in the world.

It’s devastating for Spence’s family, just as it was devastating for me when my own father developed dementia.

ST: Academic settings often appear in your novels. What do you find compelling about that world?Is Spencer Robin based on Edward Tayler, the legendary Columbia Shakespearean?

JH: No, Spencer Robin is based not on Edward Tayler but on Louis Henkin, my father. As for academic settings, that’s the world I know. I spent the first eighteen years of my life in Morningside Heights, then four years in Cambridge, then four years in Berkeley, then eight years in Ann Arbor. My life has basically been a magical mystery tour of college towns.

ST: The professor’s daughter, Sarah, mourns her ignorance of Jewish traditions. In what sense do you think Jews often fall short of an informed relationship with their own intellectual (or spiritual) legacy?

JH: It’s not for me to say who does or doesn’t fall short. For every person like Sarah, who resents her parents for not teaching her more, there’s someone like my classmates from Jewish day school who resent their parents for shoving Judaism down their throats. We all look back on our childhoods and wish for something different.

ST: In the course of the novel, Professor Robin, a brilliant scholar and “exceptional man,” develops early onset dementia. This precipitous drop, almost Shakespearean in itself, has both positive and negative effects on him and his family. Can you speak on the effects of the fall of a patriarch?

JH: It’s devastating for Spence’s family, just as it was devastating for me when my own father developed dementia. The scene when Pru takes Spence to the hospital to be diagnosed is borrowed almost entirely from my own life. I was forced to watch my brilliant father, who was a law professor for fifty years and who majored in math in college, struggle to count backward from one-hundred by sevens and name the month of the year and the President of the United States. There was a lot that was awful about going through his disease with him, but that was one of the worst moments.

ST: Pru, Spence’s wife, was once his promising student, and ever since has taken something of a subordinate role to her mentor and husband. Can you discuss Pru’s evolution throughout the story?

JH: My mother, who is eighty-eight, likes to tell a story about how when she was at Yale Law School in the 1950s, one of six women in her graduating class, the professor walked into the lecture hall one day and, seeing my mother and her friend seated in front, said, “Okay, girls, now get up and give the boys your seats.” To her own astonishment looking back, my mother relinquished her seat. She didn’t even think twice about it. My mother graduated from Yale Law School, got married, raised three sons, and eventually had a successful career as a human-rights lawyer, but her career always took a back seat to my father’s.

In Morningside Heights, I was interested in writing about a woman who essentially gives up her career for her husband. This happened fairly often, certainly in the 1960s and 1970s when Pru and Spence were coming of age, but what made Pru’s situation particularly interesting to me was that she was quite successful in her own right — she graduated from Yale herself and started a Ph.D. in English literature — then took a route she hadn’t anticipated.

ST: Has your perspective as a writer changed over the years? Do you find yourself discovering new topics or perspectives as you live through different decades of your life?

JH: A writer is always discovering new characters, new perspectives, new situations. It’s a big decision who the characters for your next novel are going to be. You’re going to be living with them for five or ten years, so you better not get bored!

ST: You head an MFA writing program. Does your writing process inform how you teach?

JH: In a lot of ways, I was a teacher and critic before I was a novelist. I mean, I always wanted to be a novelist, but it seemed as likely as my being a ballerina. But when I graduated from college, I worked for a magazine where I was the first reader of fiction manuscripts, and I saw how bad most of them were, and I thought if other people were willing to try and risk failure, I should be willing to try and risk failure, too. There are writers who are more naturally intuitive than I am. I had to teach myself to become a more intuitive writer. So teaching has helped me become a better writer, and it continues to help me every day.

ST: What is your next project?

JH: I was on leave from teaching this past fall, and I almost finished a very rough draft of a new novel. It has a speculative premise, which is unusual for me. More than that, I’m not saying.