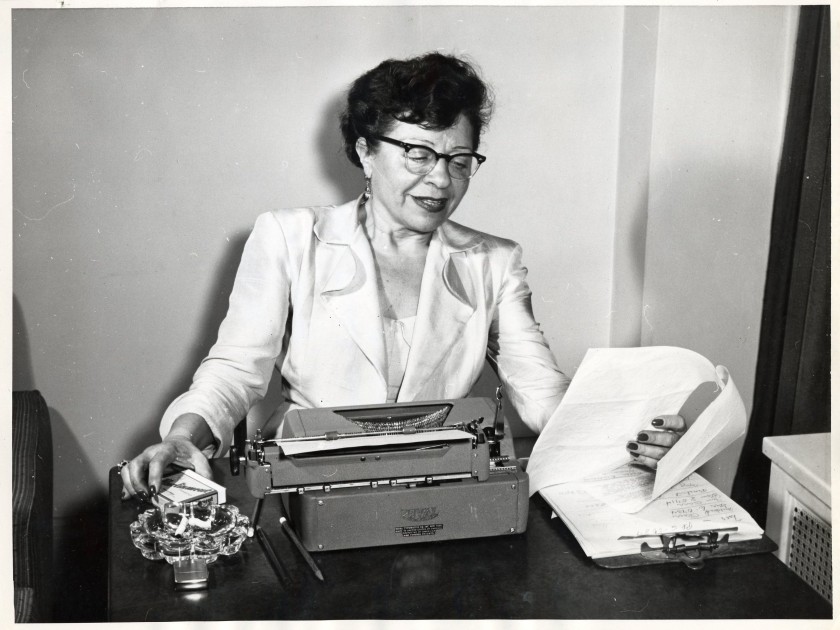

Public domain provided by the Polly Adler Collection, courtesy of Eleanor Vera.

It is an odd phenomenon, the way Jewish gangsters have been embraced by American culture. Scoundrels like Bugsy Siegel, Meyer Lansky, Dutch Schultz, and Arnold Rothstein have become cultural archetypes, whose lordly ambitions and tragic flaws are considered essential to understanding our national character. So it seems odder still that few Americans remember their sister-in-sin Polly Adler, the most notorious madam of the Jazz Age.

From 1920 to 1945, Polly reigned as New York’s “queen of the underworld.” “Madam Adler’s word was law among those who lived without the law,” as one reporter put it. The tabloids dubbed her the “Female Al Capone,” the “Jewish Jezebel,” and the “Empress of Vice.” But Polly preferred to cast herself as a topsy-turvy Horatio Alger heroine.

“A cynical person might say my life had been a typical American success story,” she observed tartly:

From the arrival at Ellis Island up the ladder rung by rung — five dollars a week, ten dollars a week a hundred dollars a week, a mink coat, a better address — from neighborhood trade to an international clientele — from a nobody to a legend.

Even as a girl in the Russian shtetl of Yanow, modern-day Belarus, Polly had grand ambitions. Born in 1900 as Pearl, she was an unusually clever and self-possessed child, who was determined to get an education in a culture where girls received little formal schooling. But as the old saying goes: “Man plans and God laughs.”

Public domain provided by the Polly Adler Collection, courtesy of Eleanor Vera.

When Pearl was thirteen, the Adlers decided to immigrate to America. As the oldest, she was the first to leave, landing on Ellis Island in December of 1913. She lived with fellow landsmen while waiting for her parents to arrive. Six months later, Europe was engulfed in war, cutting off all travel from Russia and leaving her stranded with strangers. From now on, she would have to chart her own path.

“No one starts out to be a whore,” Polly later observed. She certainly did not. But for a teenager alone in the city, with no education or skills, selling sex seemed like the answer to all her problems. “I am aware that in the judgment of the stratum of society which decides these things I should have drawn myself up and said, ‘No thank you, keep your dirty money! I’d rather sew shirts for five dollars a week,” she said defiantly. “But I am not apologizing for my decision. My feeling is that by the time there are such choices to be made, your life already has made the decision for you.”

Polly opened her first brothel in 1920 — a self-styled ‘house of assignation’ in a two-bedroom apartment across from Columbia University. But she had grander visions. “If I had to be a madam, I’d be a good madam,” she declared. “I was determined to be the best goddam madam in all America.”

By 1925, her house had become a favorite oasis for the bootleggers and gamblers who circled around Arnold Rothstein; it was the late-night hangout for the wisecracking Broadway bohemians of the Algonquin Hotel, including Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, and George S. Kaufman. The showbiz crowd soon followed; she proudly counted George Gershwin and Harpo Marx among her clientele.

She cultivated gossip columnists and influential newspapermen and patronized the chic nightclubs with a rotating posse of glamour girls. “She was a sharp businesswoman, a financial brain,” remembered one customer. “You had to be somebody to go there, and you had to pay plenty, no matter who you were or how well you knew her.”

Among the cognoscenti it was said, “that if a bomb exploded in Polly Adler’s house, the political and cultural life of the city would be wiped out.” Top executives in the garment industry, motion pictures, and advertising employed her girls to woo clients. Wall Street traders passed along stock tips on their way to the bedroom. Crooked cops made her place their home away from home. Racketeers used her parlor as an informal headquarters where they could confer with politicians and judges. She once confessed that even Franklin Delano Roosevelt had employed her services.

In 1953, Polly capped her career by publishing a memoir. A House is Not a Home became a runaway hit, selling two million copies and vaulting her to international fame. Yet, even then, she did not achieve the iconic posterity of male criminal colleagues.

But don’t count her out. “I have always been a fighter and hope to Christ I never stop till curtain time,” as she put it. Perhaps Polly’s moment has finally arrived, as a new generation grapples with the intersection of sex and power, eager to pierce the conspiracies of silence that protect powerful people from bearing the full cost of their desires.

Debby Applegate is a historian whose first book, The Most Famous Man in America: The Biography of Henry Ward Beecher, won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography and was a finalist for the Los Angeles Book Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award. She holds a Ph.D. from Yale University and lives in Connecticut with her husband Bruce Tulgan.