Lynda Schuster, author of Dirty Wars and Polished Silver, has been guest blogging for the Jewish Book Council this week as part of the Visiting Scribe series.

As I was writing my memoir, Dirty Wars and Polished Silver, I thought a lot about how journalism has changed over the decades. The book — which begins with the 1973 Yom Kippur War and ends with the 2014 Gaza War — chronicles my time as a foreign correspondent covering international conflicts for the Wall Street Journal and as the wife of a U.S. ambassador. Journalism’s transformation during those years, both in its dissemination and in the role of its practitioners, is nothing short of remarkable.

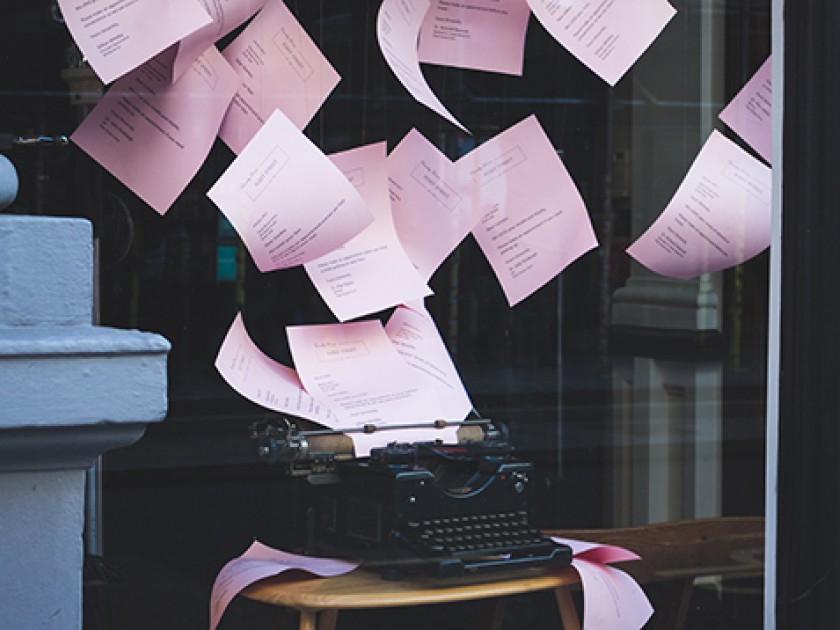

Much of the change is due, obviously, to the advent of the Internet and the rise of social media. When I started out at the Journal in the early 1980s, we were still using typewriters to bang out our copy. (That thumping noise you hear is my dinosaur tail being tucked discretely behind me.) Back then, when I wanted to file a story to the States while covering the wars in Central America, say, I had to be beg, plead, cajole — bribe, even — the telex operator at my hotel. And that assumed the power grid hadn’t been attacked. Barring a sympathetic hotel typist, I had to strike out, often in the dead of night to make my deadline, to the city’s central telephone exchange. Still, there was something thrilling about the clacking, clattering noise of the machine sending your story.

The years passed, and the technology improved. My first portable computer could accommodate about three sentences on the screen; to send a story, I had to fit rubber cups over the ear- and mouthpiece of a telephone. (That telephones even had mouthpieces tells you right there this is ancient history.) Those computers were prone to epic failures. Once, after writing up a story in Buenos Aires that I had spent several days reporting, I flew to Rio de Janeiro with the intention of filing the piece from there. (I was on a crazy deadline to finish a Brazilian story as well.) As soon I got to my stringer’s office, I attached the cups, dialed New York, pressed “send” — and pouf! The story disappeared. Gone. Vanished forever. The computer had neither hard drive nor memory — and I had nothing to file. So I did what any self-respecting reporter on deadline would do: I panicked. Once I’d finished hyperventilating, though, I sat down and miraculously recreated the story from memory. After I made deadline, my editor — who apparently liked the article I’d pieced together — said: “Maybe you ought to try losing your stories more often.”

Fast forward to today, with all the fancy, light-as-air laptops and instantaneous means of transmission. But while the Internet has made the actual job of journalism easier, social media is, in many ways, rendering reporters superfluous. That’s especially true when it comes to foreign reportage.

First, consider the vital role as conduits that we journalists used to play. When I covered southern Africa in the late 1980s, the civil war in Angola — a proxy conflict for Cold War supremacy in the region — had been raging for almost fifteen years. Amid talk of a possible peace accord, another reporter and I were flown by the South African military to Angola to interview the head of the rebels. We arrived at their base — only to find the rebel leader had flown off an hour earlier to consult with the president of a West African country. His armed soldiers made it clear, however, that we were to remain as their “guests” until the leader returned. And there we were, stuck in a place so remote the former Portuguese colonists called it “the land at the end of the earth.” No means of communication, no way of getting out (the South Africans left after dropping us off), nothing to do but sit in a hut and wait. For days. Until the leader returned: laughing off our consternation at being held hostage, he gave us a lengthy interview, then summoned a plane to return us to South Africa.

The rebel chief had wanted his opinion of the pending peace accord transmitted to the world — and we were the only means to do so. Nowadays, that wouldn’t happen. The rebels most likely would possess their own website, Facebook and Twitter accounts, all manner of methods to disseminate their message without having to rely on journalists. Which accounts, in some ways, for tragedies such as the beheading by ISIS of reporter James Foley in 2014: we are more valuable as pawns to garner international attention than as interlocutors.

Yet one essential thing about the profession hasn’t changed. Witness the remarkable reporting of late by the New York Times and Washington Post, among others, on matters that otherwise would have remained unknown to us citizens. No amount of technological transformation can ever replace that cornerstone of our democracy.

Lynda Schuster is a former foreign correspondent for the Wall Street Journal and Christian Science Monitor. She reported from Central and South America Mexico the Middle East and Africa. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times Sunday Magazine, The Atlantic, Granta, and Utne Reader. She is also the author of A Burning Hunger: One Family’s Struggle Against Apartheid.