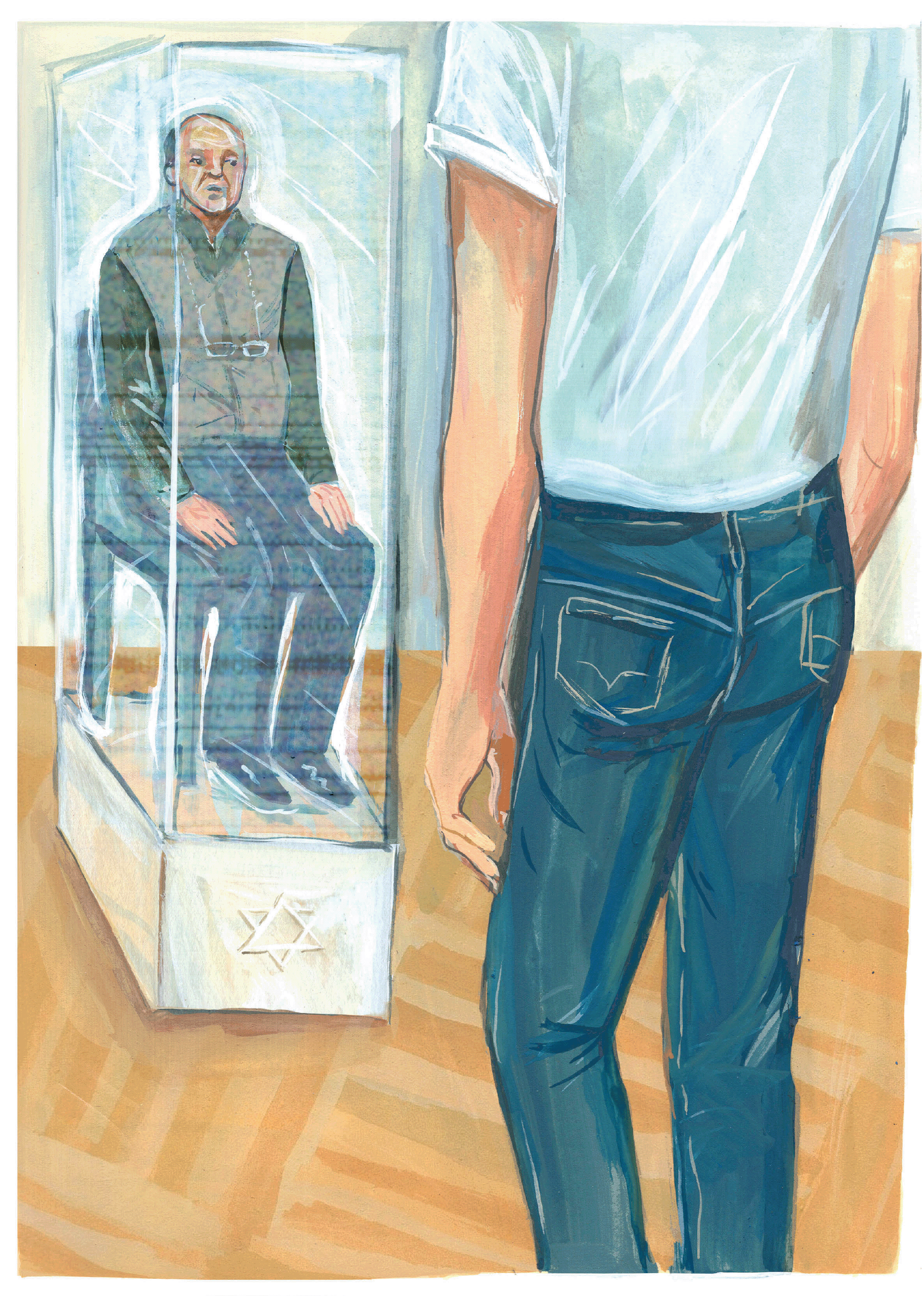

Illustration, cropped, by Jenny Kroik

Join Adam Schorin and Paper Brigade’s editors for the final installment of Paper Brigade’s Short Story Club this season on April 3rd at 12:30 p.m. ET. Register here!

We were waiting in line at the Holocaust Museum on Prinzenstrasse when I realized I had to pee. We were there to see the holograms: the exhibit had just opened and Rayon Fabula said she wanted to go. I wasn’t particularly interested, but once a few of the others got excited, they stuck to me like scabs to a wound.

It ended up being five of us: Rayon, Butch Acidy, Vulva Incognita, Maurice, and me. We were all performing later that evening and Vulva, who would be on first and had already painted most of her face, stepped out of line to check her reflection in the empty glass boxes that stood like sentinels in the lobby. These were relics from some six months ago, when the museum had invited Jews to sit inside them so visitors could assail them with questions about being Jewish. “It’s a shame you missed it, Sammy,” said Vulva, dabbing her lips with a napkin. “It was so wonderful, so important. You could have been a Jew in a Box.”

In the months I’d been living in Berlin, the subject of Jewishness had popped up like houses in the headlights of a nighttime drive. Though I was not what you could call a practicing Jew — with the exception of star charts and tarot apps, our world in Berlin was unerringly secular — everyone wanted to talk to me about it. Young Germans were often expressively apologetic, eager to absorb my thoughts on the city’s various monuments and memorials to murdered Jews. They invited me on trips to Sachsenhausen and Gleis 17, debated the best mason jar salads at Topography of Terror. They took care to vilify the far right in my presence, referencing outrageous tweets, the latest news of foiled insurrections. “It’s horrifying how these ’patriots’ carry on,” Rayon spat out one evening, hands numb on G. “The never-ending wet dream for Hitler.” She waited for me to weigh in, to solemnly agree, which I eventually did. Others felt obliged to point out how far Germany had come in the last eight decades, how it had more than atoned for its sins. “How many refugees has the US taken in this year?” Gravlax Nuts asked heatedly in the bathroom. She was wiping off her face in the mirror while I untucked by the toilet. “I mean seriously,” she said. “We’re the fucking moral leaders of the planet.”

Worst of all were the fetishists, the Star of David – wearing non-Jews who felt the path forward was through a kind of ethnospiritual imitation. They heaped praise on the State of Israel and fulminated against this or that latest expression of European antisemitism, which they saw happening everywhere, all the time. They tagged each other in recipes for kugel, falafel, and borscht. In the bathroom queue at Jockbox, sharing a cigarette by the KitKat pool, they hinted that they had never seen a circumcised dick before. “I want a tattoo in Aramaic,” whispered a young man at a party, clearly priapic. “Something from Kabbalah. Where do you think it would look sexy?” They peppered their speech with Yiddishisms, offered to teach me German in exchange for Hebrew, a language I did not speak.

I tried to exit these interactions as quickly as possible, or avoid them altogether. I wished desperately to live in Berlin with as blank a presentation I could manage, without the weight of a Galician surname, my lack of a foreskin underwriting each encounter. More than being American, it was this that I hoped to scrape clean from my body, to exfoliate by steel wool and wash down the drain. And yet. And yet — part of me, I knew, felt entitled to this place, to as much of it as I wanted. I believed on some level that I was owed something, that any Jew here had a debt to cash: from the ground, the buildings, the air. I wore fake tits on streets where, eighty years earlier, Jews had been tossed from their homes, executed en masse. I gummed ketamine in the basements of onetime Gestapo holding cells, gave reacharounds to the grandchildren of Luftwaffe pilots. Even as I dodged all things Jewish in conversation, the very fabric of the city was awash with them. Though as far as I knew none of my family had ever lived or passed through the city, I felt I had its title and deed, blind permission to behave any way I wanted. I was louder, for one thing, on the streets of Berlin than I had ever been in Manhattan. I shouted to friends, swore on the phone, shredded cigarettes with my heel. I was bigger and broader in my movements. On early-morning walks home, stomach gloopy from the diet of mephedrone and Späti beers and maybe vodka that had sustained me through the night, I sometimes threw up on the sidewalk — not into the dirt, or a trash bin, but in the middle of a concrete slab. Because if that wasn’t permitted me, what was? Who had ownership over these streets if not someone like me? I wanted at once to vanish in the crowd of other expats, other queers, and to stake my moral claim over the city in permanent ink, for my bile to burn the words in the ground: Sammy Raubach was here.

______

</p>

<p>

The museum was housed in a large, squat prewar building, an Art Deco-cum-Bauhaus thing that took up half a block. The line snaked four or five times across the width of the lobby before getting to security, where a woman in a fur hat prodded visitors with a metal rod and two impossibly old men stared at a screen next to the conveyor belt. Occasionally, an alarm went off. Butch Acidy pursed her lips, scrunching her mustache into a caterpillar. “I hope it’s worth it,” she said.

Last night, Rayon had sent around a video from the museum’s YouTube page promoting the holograms exhibit. For the last several years, explained a voiceover, an American Jewish foundation had been filming Holocaust survivors answering some two thousand questions each. The survivors were captured from nearly 360 degrees, each sitting in a straight-backed red armchair in the center of an orb of cameras, lights, and green screen. The video showed several of the survivors nodding approvingly at the contraption around them. Employing a technique developed by a nineteenth-century British stage magician, the footage was projected through a plastic screen to give the impression of a 3D hologram. (According to the video, true holograms, the kind from Star Wars and Back to the Future, did not yet exist. Who knew?) In museums around the world, visitors could ask the Holocaust holograms about their experiences during the war: using the same speech-recognition software as our smartphones, the hologram identified keywords in each question and scanned hours of footage to project the most relevant clip as an answer — all this described by a woman in a lab coat with the words Holocaust Sciences stitched in blue above the breast pocket. “Until the end of time, future generations will have access to the stories and wisdom of these extraordinary individuals,” the woman told the camera. “You know how Superman talks to his father in the Fortress of Solitude even though his dad died years ago? This is the Fortress of Solitude.”

It was an old man, though not as old as I had been prepared for, in a green

button-down, felt vest, and slacks. There was something in how he had been filmed that made every part of him<span class=“nobr”> appear equally in focus in a way that people<span class=“nobr”> in life are not.

We sent our purses and tote bags through the conveyor belt. Maurice wore a high-end trail-runner pack and had to unclip several straps before removing it from his steel drum of a torso. We entered the exhibition hall with our ticket stubs and were met with a vast white space filled with people. Holograms had been set up on three of the walls — the far side, the left, and the one through which we’d entered — and groups were gathered in front of each, asking questions into dangling microphones. The long right wall of the room held a series of panels with text too far away to read. Visitors milled about the center of the room, shuffling between the groups like bingo balls. I scanned above their heads, looking for a sign for the bathroom, but then Rayon was grabbing my arm and pulling me to join the group on the left.

Our hologram was situated at the crest of a half-moon alcove in the wall, a little crowd huddled before it. It was an old man, though not as old as I had been prepared for, in a green button-down, felt vest, and slacks. Glasses hung from a knotted string around his neck. There was something in how he had been filmed that made every part of him appear equally in focus in a way that people in life are not. This recalled the hyper-realistic sketches that sometimes spammed me on Facebook, the kind you first mistake for photographs. His entire figure was limned by a shimmery half-centimeter, like the curdled air above a sweltering freeway.

“How many concentration camps were you in?” a boy, American, was asking when we arrived. A placard in front of the hologram said his name was Simon Ausfelder; he was born in Hamburg; he lived in Miami; he was eighty-six when the interview was recorded.

“I was imprisoned in three of the Nazi German concentration camps,” said Simon Ausfelder. “I was taken first to Sachsenhausen, then east to Gleiwitz, which was part of the machinery of Auschwitz, and finally back west to Dachau. I was liberated at Dachau.” He leaned forward as he said this, touching the tips of his fingers together like there was a delicate specimen, a butterfly’s wing, between them. His gaze rested a few inches above us.

When he finished speaking, he flickered as he shifted back to his resting pose. The promo video had explained that the footage was touched up and lightly animated, the survivors’ gestures augmented by CGI, so that different clips could be seamlessly cut together. But it gave the impression of a cartoon scientist being electrocuted, the boundaries of his figure rapidly realigning.

“What’s the worst thing that happened to you?” This from an Irishman in an Orlando Magic jersey. The woman with him punched his arm.

Simon Ausfelder shuddered into a hunched pose — the electricity again — and rubbed his forehead. “The worst thing? It is hard to say what was the worst, when every hour presented so many new atrocities,” he said. “Each day you thought was the worst day you had ever lived, but always the next one was worse. Our only moments of freedom, of privacy from the gaze of the guards or the kapos, was in the latrines. We sat over holes in a long bench, like animals. It was disgusting, but the guards did not watch, so there we could be a little free.”

My bladder pinched my abdomen, made me feel heavy and alert. “Just go,” Maurice whispered. “We’ll still be here.”

I was surprised that he could tell. “It’s fine,” I said. “I can wait.” I hunched forward, easing the pressure.

Illustration by Jenny Kroik

An older woman with a hard-to-place accent was standing at the mic. She said, “Are you real?”

Simon Ausfelder smiled and spread his arms wide. “I am a real person!” he announced, and a handful of tourists beside me clapped. This meant, of course, that the labcoat people had thought to prepare the survivors for this question: one of the two thousand they had asked was, simply, Are you real? In the promo video, we had also seen survivors answer the questions What did you have for breakfast? and What is your favorite television show? Simon Ausfelder seemed calm and in control — his gentle, bobbing smile held the attention of the crowd. It was the same poise Rayon brought to the stage, that I hoped one day to project as well: light and welcoming, confident but innocuous.

I tried to mirror his smile, but on my lips it felt gimmicky, cheap, like I had drawn it in clown paint. The faces around me, now that the applause had settled, were solemn and expectant — I buried my underwhelming smile, lest they think I was having fun.

Both my mother’s parents were survivors. When I was little, my grandmother came a few times to our school to share her story. My classmates, mostly Jewish, a few with survivor relatives of their own, faced forward, sparing her a modicum of attention. Even at that age, I knew her story so well that it seemed part of my story, like any of the cartoons I watched millions of times with my brother, encoded so deep in my memory that I could not be entirely sure that it wasn’t I who had chased a little brown mouse with axes and explosives, not I who had pulled the sword from the stone. Stories repeated to the cadences of fiction, the foundational myths of my childhood. This proprietary slippage — I perked up if she added a new detail or substituted a location, as though some cluster in my brain wanted to cry out: But that’s not how I remember it! At the parts I knew would get the biggest reaction — her brother’s swift illness in the gulag, the mass dehydration and death in the train cars — I studied the faces of my peers, deciding if they expressed enough alarm, enough horror. It was good when one girl burst into tears. When it was time to ask her questions, the class turned to me, as if I couldn’t ask her whenever I wanted, as if they could only reach her through me. Only occasionally did they actually pose a question, most often if her life made her happy now.

My grandfather, on the other hand, I had barely known. Though he died only recently, he had run off with the babysitter some fifty years ago, leaving my grandmother to raise two kids and casting himself forever in estranged mystery. Though she rarely had nightmares about the Nazis or Siberia, at least by the time of my childhood, she often awoke cursing his name. Soon after he died, my mother received in the mail a DVD stamped with the name of one of the main survivor testimony archives in the US. When she popped it in, all we could see was a menu page, with blocky WordArt text bouncing around the frame: Joe “Janusz” Wexler’s Story of Survival. We tried clicking Play, Chapters, Back, but nothing worked. Only when we hit Eject, right before the disc slid out, did an image pinwheel into existence, a low-resolution photo of my grandfather in a winter coat standing on a bridge somewhere, probably in Europe.

I knew my grandmother’s story so well that it seemed part of my story, like any of the cartoons I watched millions of times with my brother.

A young woman in front of us asked something in German and, though it was Simon Ausfelder’s native language, the hologram did not react. The guy with her — there were, I noticed, a fair amount of couples in the crowd — took the mic instead and said, “What do you think about Germany today?”

Simon Ausfelder scratched his brow. “Though I am certain there have been a great many progresses in the German country,” he said, “I know I will never return. It is a place, a society, that betrayed me too deeply for any hope of reconciliation.”

The audience responded with knowing nods, as if a spirit from some other world had passed over us, tilting our heads. Someone behind me whispered, in English, “Who does he think paid for this exhibit? Whose tax dollars are at work here?”

I turned to see who had spoken, but was bumped back by a pair of Scandinavians hauling mammoth backpacks. “Entschuldigung, entschuldigung,” they tittered, and the crowd parted around them, the faces all preoccupied with the intrusion and therefore the same, the speaker vanishing in plain sight among them. More pressingly, the dull knock of the backpacks, which would anyway have been minorly discomforting with my bladder distended as it was, sent a long spasm of pain through my groin and abdomen due to the fact that, though I would not be on stage till late in the evening, I was already tucked and my testes, stowed high on either side of my mons, and pillowing the surface of the skin into a soft valley, took the full force of the blow. As the initial hurt subsided, coiling to a sickly thrum, I was awakened as well to the itchy tug of tape across my butt to my lower back. I had not yet told the others, nor did I plan to, but I had recently begun tucking hours before taking the stage and even on some days when I did not perform at all. This, I feel bound to say, was not out of any yonic aspiration or female fantasy — I was steadfast in my gender, my maleness. In fact, if it had been some trans experimentation, I would have had no problem sharing it with the other queens. But this tucking felt closer to something I often caught myself doing: harping over gadgets and techniques, hoarding the paraphernalia of a new pastime. I had been performing drag only a few months. Though I told myself I was merely acclimatizing my inguinal canals to the process of stuffing my testes inside them — a sensation that echoed the odd, low ache of a cresting rollercoaster — I knew it was born instead of the same flash-pan obsessiveness I had brought to dozens of discarded adolescent hobbies, becoming rapidly well-versed in the jargon of jazz guitar, fencing, astronomy, skateboarding, sewing, and so on, the amps and épées and telescope and all else my parents had gladly bought me now gathering dust in the closet of my childhood bedroom, or else donated to some anonymous preteen who might actually make use of what for me had long ago become trash. It made plain my desperation: a level of googly-eyed enthusiasm that automatically relegated me to the realm of outsider, fan, poser.

Vulva approached the mic, coughing into her elbow. The people nearest her turned and gazed. At nearly seven feet, bald, and Black, Vulva was used to drawing stares in a German crowd, especially with her face lightly contoured, her eyes framed in a smoky blue wave. “It is so special to meet you,” she said. I stepped from foot to foot, hoping to tamp down the lasting pain.

The hologram nodded gently, its eyes following something off camera, perhaps a fly in the recording studio.

Vulva pressed her palms together below her chin, a dopey namaste. “What would you most like people to remember about your story?”

Simon Ausfelder made a gesture like popping his lips — or like he was air-kissing away excess lipstick, as Vulva had just done in the lobby. He said, “What I would like my story, the legacy of my story, to be is really quite simple.”

I had expected most of the questions asked of the hologram to be obvious and banal, as so far they had been, but that Vulva’s should also be so dull was irksome. Not that I was surprised — I had sat blank-faced in the stream of many of her soliloquies on postwar memory in Germany, diatribes that for all their originality could be summed up as Nazis = bad—but I hated to be included in her coterie, to be seen by the other visitors as with her as she lobbed the most basic of basic questions at the screen. But what did I know? Maybe this was exactly what the real Simon Ausfelder most wished to be asked.

“There is a time for remembering and a time for forgetting,” the hologram was saying, “and it is important always to know which is which.”

In her stories, my grandmother tended toward hyperbole. Her mother was the kindest, the best; her dead brother an angel from above. Numbers were always in the millions, catastrophes always “like you would not believe.” The only villains in her stories were antisemites, the Nazis, the Soviets, and her various husbands. And they were Old Testament villains, the stuff of fire and sulfur, the wrath of God. There were no complex characters, no shades of morality. In the final years of her life, her speech was marked as well by unlikely similes. The wind howled like a greedy ogre; I had cheekbones that could kill the president. And she became cruel, often shouting at my mother that she was vile, that everything from her hair to her shoes wasn’t worth an ounce of dust. One afternoon, as I scrambled eggs for her lunch, she lapsed into a long silence, which she broke only to say, apropos of nothing, that I disgusted her.

“I wanted justice,” Simon Ausfelder said. Tears welled in his eyes, glimmering with supernatural clarity. “But this is the best I can do.”

This was met with vigorous applause.

Vulva blushed, pleased to have asked the question that had elicited the answer that had elicited such a reaction from the crowd.

Rayon beamed beside her; Maurice pecked her shoulder. Nothing so much as the grace of others can shame you for your own ungenerous thoughts. Still, I wanted to say to the crowd: Why, exactly, are you clapping?

I was, as well, keenly aware of the fact that at any moment I could leave all this behind: drag, Berlin, my friends here.

Vulva was the one I least wanted to know about my off-day tucking. When she started performing a few years ago, she still lived her life offstage as Daniel. Only in recent months had Daniel ceased to exist: even out of makeup, out of costume, she introduced herself as Vulva Incognita. Never before had I met someone who had created a character out of thin air, developed her for years, and then simply become her. It seemed like a different kind of transition — she had made the make-believe real, the performance the thing itself. My heart grew weary when I imagined her walking home alone after shows, how vulnerable she was. She waxed lyrical about the suffering history had dealt me — not even me, nor my parents, but my grandparents — and I worried about her in the present, the future. What violence could befall her at any unguarded moment. “Are you going to start PayPaling me?” she said once, when I brought up the issue of her safety. “The bipoc trans tax?” I pictured her face bashed in, her lengthy figure pooling blood, police swarming an S‑Bahn platform. I was, as well, keenly aware of the fact that at any moment I could leave all this behind: drag, Berlin, my friends here. In less than a week, if I wanted to, I could pack up my flat, move home, back to school, pick up my life where I had left it — my former life, in its entirety, still eminently available to me. For the others, and I suspected especially for Vulva, Berlin was by no means a vacation, not reality put on hold.

Butch Acidy, now up, said, “Excuse me,” and the hologram turned its head, quickly, in the wrong direction. Scattered laughs. Butch asked about daily life in the camps and Simon Ausfelder told a few stories. His voice had turned thin and breathy; the crowd had to lean forward to hear him. Later that night, on stage, Butch would stab herself through a balloon heart, hidden in her bra, and smear her entire body with the red shampoo that would burst forth. I tried not to associate the whispers behind me with the sound of a running tap, a laden stream.

“We had to dig trenches in the sand,” Simon Ausfelder said. “Every night, even after we had finished our other work. In the cold, it was like your hands were made of porridge.”

A beefy guy stepped up to the mic, interrupting. “Wait, sand? Why was there sand?”

The hologram stuttered, shifting positions, until Simon Ausfelder was leaning forward, a hoarse chuckle rolling from his lips. “I’m sorry,” he said. “I don’t understand the question.”

We had learned from a pamphlet in the lobby that one of the eventual goals of the holograms project was for them to be able to hold actual conversations. This would entail the AI crafting dialogue on the survivors’ behalf, fleshing out speech the recorded testimony did not include and making moments like this one impossible. It was important, the pamphlet said, that the interactions with the survivors feel natural; the invented video would be “true, of course, to the individual’s intentions and the raw facts of his or her life.” This part of the program had yet to be implemented, though the researchers were confident it was only a few years away.

When no one spoke, Simon Ausfelder once again recombobulated — a crossfade and his hands were on his knees. He said, “Does anyone have a question for me?”

______

</p>

<p>

By now, I really had to pee. With my penis wrapped and contorted as it was, the urge to piss was unlike any I had felt before, flitting out across my groin and hips, searching for a place to land. It was as if my body was experiencing it for the first time, replicating the sensation from hearsay, like the goofy and lopsided medieval etchings of lions, Frankensteinian amalgams based on distant accounts. The tips of my fingers were warm; the back of my neck pricked like it was right beneath a fan. What did I really know of my grandmother’s life, other than what she had told me? What had I actually seen?

“Sammy, Sammy.” Rayon waved over the heads between us. “Do you want to ask something?”

“No,” I said.

“Come on,” said Vulva. “It’s fun.”

The crowd shepherded me to the mic. Maurice squeezed my hand. The hologram nodded politely, waiting. I tried to think of something to say that would mark me as special, unique from the generic askers of generic questions who had already approached the mic. Someone touched as well by the same forces that had ripped Simon Ausfelder from his home, sent him through these horrors, and deposited him, at last, on the sun-baked beaches of Miami. What I wanted to know, I suppose, was if the real Simon Ausfelder had met his hologram or watched it tell his stories. Would he have been comforted by the rendering—What a lovely gleam in the eyes! What presence!—or would he have been burdened to know that this would be his voice on Earth, his translucent avatar for the rest of time? I wondered what he would make of this horde of Germans and tourists, less than three hundred kilometers from his place of birth, gushing over his likeness. How would he have reacted watching himself say, “I don’t understand”?

I said, “Why did you want to participate in this project?”

The hologram scratched its head, shimmered.

“What I would like my story, the legacy of my story,” it said again.

Some people laughed. A few booed. A boy filming the interaction on his phone said, “We already heard this one!” He must have spoken close enough to the mic because, mid-word, the hologram glitched back into its neutral position, the last syllable cut in half by that inviting smile.

I was pushed aside so someone could ask the next question. I was surprised to feel embarrassed. Rayon whispered, “Do you want to try again?”

I squeezed back through the crowd to find the bathroom, a sign for which I now saw was posted at the far end of the room, in the corner past the panels of text. My balls ached along with my bladder: pressed near each other, the aches felt in one moment distinct and in the next joined together, a new sensation, the synapses firing in cramped confusion. I took wide cowboy steps, my chin hanging ahead of my feet.

Finally — the bathroom. A few men bumped into me on their way out, but still there were more waiting inside, all the stalls occupied. The voices of the headscarf-wearing hologram and the crowd came through the door as a pleasant rumble, like we were underwater. I tried to focus on the light in the center of the ceiling, counting down from ten again and again, until at last there was a spot for me. In the stall, I shucked off my pants and underwear and reached around to rip off the tape from my lower back. Though scrunched with sweat, the tape did not budge. On stage, I usually used medical tape for tucking, and though my shaft and scrotum were sheathed in a few of those gauzy strips, I had learned from experience that it would not hold for more than half a day in the summer heat. So lately, for the securing strips that chevroned my ass, I had turned to a thick black tape designed for plugging holes in the hulls of boats. I usually soaked it off in the bath, or else was able to dig my fingernails in and slowly, carefully peel it off, gauging my progress in the mirror. But, for whatever reason, now I could not. My penis would have to stay tucked.

I positioned myself above the bowl, my ass hovering over the center. I did not even know if I could piss with my genitals in their current configuration. I pictured a bent straw, a snagged hose: pressure, buildup, tragic explosion. I took hold of both sides of the seat and, with a final, heroic umph, hoisted my feet so that my boots, now so heavy, pressed against the narrow frame on either side of the door and my chest table-topped flat and horizontal. Tilting wildly back, my head landed against the tank and I glimpsed, through the high window running the length of the wall, a narrow shock of blue sky. Was the real Simon Ausfelder still alive?

A few seconds of focused effort and then a halting, perilous stream, whose only confirmation of accuracy was the soft pit-pittle that echoed up the sides of the stall. How did I appear from above — boxed in, contorted? The pain lessened with each spurt of urine. I thought of the others waiting for me outside, the conversation they would be having about how moving the whole experience had been. Or maybe they had wandered over to the other holograms. Some hours from now, we would all be on stage together, belting out “I Say a Little Prayer” for our closing number. The stream grew steady, more assured, my bladder heaving itself out. I was pathetic. My palms were already slick with sweat, but my fingers clamped the seat tight, and I breathed in great gasps of air. The ceiling, I saw, was decorated in small tiles, a mosaic maybe, dull flashes of blue and red that at one point had surely been brilliant. I waited for a pattern to emerge, or for whatever larger image they depicted to condense into something clear and apparent, but the tiles were all cracked and coated in decades of dust and grime, so they remained as they were, ancient and unknown.

Adam Schorin is a writer based in Warsaw. His short fiction and nonfiction have been published in ZYZZYVA and The Forward, among others. He is writing and producing a documentary directed by Michel Franco, to be released next year.