From 2018 to 2020, journalist Abigail Pogrebin (a Reform Jew) and Rabbi Dov Linzer (president of the Orthodox seminary Yeshivat Chovevei Torah in Riverdale, NY) started an unusual havruta. They talked through every parsha of the Torah —across significant chasms of difference in opinion — with the discipline of scholarship and with profound honesty. These were turbulent years marked by an increase in partisanship, fissures around immigration, the shock and isolation of the COVID pandemic, and the racial reckoning after George Floyd’s murder.

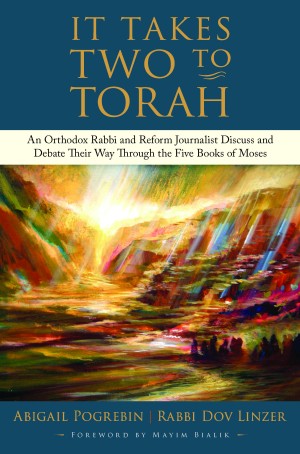

Pogrebin and Linzer recorded their conversations for a podcast that has now been adapted into a book, It Takes Two to Torah, that captures the lively dialogue and discourse of their discussions.

JBC asked them to have one more conversation about a key subject in the Torah that they might have left out from their initial talks and wished they’d had the chance to delve into.

Dov Linzer: Abby, in our two years talking Torah together, we never covered the central affirmation of faith – the Shema. How could we have skipped that?

Abigail Pogrebin: It’s a shanda that we did, but it has new resonance now, after October 7th, when so many Jews in America are feeling a strong pull to proclaim – or at least reckon with – their Jewishness, especially as a response to the surge in antisemitism. The Shema has taken on new weight, new defiance. I’m always stirred by the realization that this prayer joins every Jew in every nation. A global prayer of Peoplehood.

DL: Me too – it’s the oath that binds us all. And the Shema is not just a verbal affirmation of our Jewish identity. It functions as a physical symbol of identity. The words are inside the mezuzah, which marks our home as a Jewish one, and those same words are in our tefillin, marking our bodies as Jewish as well.

AP: Nobody would be wearing those black boxes if they weren’t Jewish, that’s for sure.

DL: Exactly. And we’ve seen, sadly, how Jews in Europe and even the US have had to weigh whether to take down the mezuzah from their front doors because they feel a need to hide, or at least not advertise, their Jewishness, for fear of being attacked.

AP: At the same time, I’ve seen how the recent upsetting events are motivating people to make more public affirmations of their Jewish identity and solidarity, to wear a kippah or a Jewish star, to put a mezuzah up for the first time.

DL: Absolutely. Let’s turn to the text, shall we? We are in the last book of the Hebrew Bible, Deuteronomy 6:4 – 9.

AP: Moses is relaying God’s instructions to the Israelites – right after Moses laid out the Ten Commandments and just before his people will cross into the Promised Land. Will you read the verses?

DL: “Hear, O Israel! The Lord is our God, the Lord is one.

You shall love your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might.

Take to heart these instructions with which I charge you this day.

Impress them upon your children. Recite them when you stay at home and when you are away, when you lie down and when you get up.

Bind them as a sign on your hand and let them serve as a symbol on your forehead;

inscribe them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates.”

AP: It’s so straightforward and forceful in its economy.

DL: Yes, and these words are part of the fabric of the traditional Jewish day. Three times we essentially affirm, “I am a Jew; here is what I believe.” Once during morning and evening prayers, once at bedtime, because for generations, that became a customary ritual.

AP: It’s curious to me that the Shema pledge starts with the word, “Hear.” Why do you think that’s the directive – instead of a command to do? Why listen instead of act? Especially since we just came from the scene on Mount Sinai, when the Israelites received the law and responded, “We will do and we will listen.” The doing came first, which suggests that deeds are paramount.

DL: Maybe since so much of what follows in the Torah is all about mitzvot – what we do, the Shema is returning us to the “we will hear” part that we promised at Sinai. It suggests something more inward: we need to internalize the commitment to God, to the law, and to the life of a Jew. This gets to the why of what we are doing. It’s a reminder to be reflective.

AP: Let’s talk about this line, “with all your heart and with all your soul.” The all-ness is noticeable. Moses doesn’t just tell us to love God, but to love God with everything we’ve got.

DL: Right. “All your heart” is understood to mean, “love God with all our emotions” – no matter what we’re feeling, and “all your soul” is understood to mean, “with all your thoughts and intellect,” and “all your might.”

AP: Why “might”? What does it mean to love with force or with strength?

DL: The simple meaning is essentially, “with great muchness.” With excessiveness. It’s to underscore a lot. It can also be understood to mean “all your wealth.” And the rabbis also offer a theological interpretation: they read the word meod in the verse – “a lot” – to be connected to the word middah, which has a similar sound. Middah means “measure,” so the rabbis explain that whatever God measures out for you – whether you’re experiencing good or bad fortune – you should be thankful.

AP: That touches a chord with me because I have to confess that I recite the Shema every night before sleep, and I’m aware that I’m saying it – and striving to mean it–no matter what awful thing has happened in the world or to someone I care about. In other words, I’m re-committing to faith regardless of whether I can fathom why God allowed something terrible to happen.

DL: Abby, that’s actually an idea that challenges me. Because when I recite the Shema at night, my goal is to just generally think about God as the last thought to end the day. But because of what you just said, I’d like to start incorporating your intention. Thank you for that.

AP: You are very welcome.

DL: Let’s turn to the end verses: “Inscribe them on your doorposts.” This is the mitzvah of mezuzah: to take a tiny scroll with the Shema prayer and affix it to the entry of our house. Do you have mezuzot up on your door frames?

AP: I do, but I don’t touch or kiss them when I walk in and out.

DL: For a lot of my life, I also wouldn’t kiss the mezuzah. I took a very rationalist approach. My not-kissing was a statement: “I’m not superstitious – I don’t feel, as some do, like the mezuzah is a magic charm that protects the house.” But then I realized it’s such an important part of God-consciousness to kiss or touch the mezuzah going in and out. That’s the whole point of it: you stop and think, especially at moments of transition, when we are moving from our public space – and public persona – to our private one, or vice versa.

AP: I love that. Maybe I’ll start kissing my mezuzah, too.

DL: It looks like we might change each other’s Shema practices.

AP: Before we end, let’s talk about the word “impress” in the line, “Impress them upon your children.” (Deut 6:7) When you think about the other words in this litany – “impress…bind….inscribe” – they suggest to me almost like a branding. We are making a promise to physicalize this commitment to God: put it visibly on our body.

DL: That is so true. The Rabbis compare tefillin to exactly that – to a brand that the owner places on his slave.

AP: I don’t love the slave analogy at all.

DL: Well, we can’t avoid the way things used to be in the ancient world.

AP: When I laid tefillin one time – right before I became a bat mitzvah at age forty – I felt like I might cut off my circulation.

DL: I can tell you that after doing it daily over many years, one learns how to wrap it without making it too tight.

AP: But the leather straps do leave marks.

DL: Absolutely. You’re left with the indentations after you take it off.

AP: How do you feel about those grooves? Are they symbolic of your daily faith?

DL: I never thought about it actually, but seeing marks on someone’s arm is the classic way you know if somebody has just come from shul. It puts a kind of insignia on your body in a way that a kippah or tallit doesn’t. Think about the parsha’s language, “write them on the mezuzot.” The Hebrew word “mezuzah” actually means door post, it doesn’t refer to the scroll itself. So the literal sense of the verse is that you actually write it directly onto your house. You don’t just attach the scroll.

AP: That’s even more permanent than a scroll you can transport or take down.

DL: Yes, it goes back to the question so many Jews are asking themselves today: how publicly Jewish to be.

AP: Let’s talk about the consistency that’s prescribed in this verse – that you should be engaging the Torah no matter where you are in your day. “Recite them when you stay at home and when you are away, when you lie down and when you get up.”

DL: Yes, the idea is that you should always be talking about Torah – these words should always be on your heart.

AP: It feels important that the charge is to “recite” – to speak it, discuss it, be in conversation about Torah every waking hour.

DL: That’s where the project that you and I undertook – parsing every parsha on a regular basis out loud together – was a fulfillment of that command. As it is every time anyone learns or brings Torah into their lives.

AP: Our connective tissue is the recitation of – and engagement with – this book. Every time we return to the Shema, we’re declaring, “This is who I am.”

DL: Yes, the Shema says, I am not just a Jew, but a public one – visible in the black box on my forehead, the indentations on my arms, the mezuzah on my door.

AP: No matter who would prefer we hide or disappear.

It Takes Two to Torah: An Orthodox Rabbi and Reform Journalist Discuss and Debate Their Way Through the Five Books of Moses by Abigail Pogrebin and Dov Linzer

Abigail Pogrebin is the author of My Jewish Year: 18 Holidays, One Wondering Jew which was a finalist for a 2017 JBC National Jewish Book Award and Stars of David: Prominent Jews Talk About Being Jewish. She has written for The Atlantic, The Forward, and Tablet, and moderates conversations for The Streicker Center and Jewish Broadcasting Service.

Rabbi Dov Linzer is the President and Rabbinic Head of YCT Rabbinical School of Yeshivat Chovevei Torah. He has written for The Forward, Tablet and The New York Times and published over 100 teshuvot (responsa) and scholarly articles.