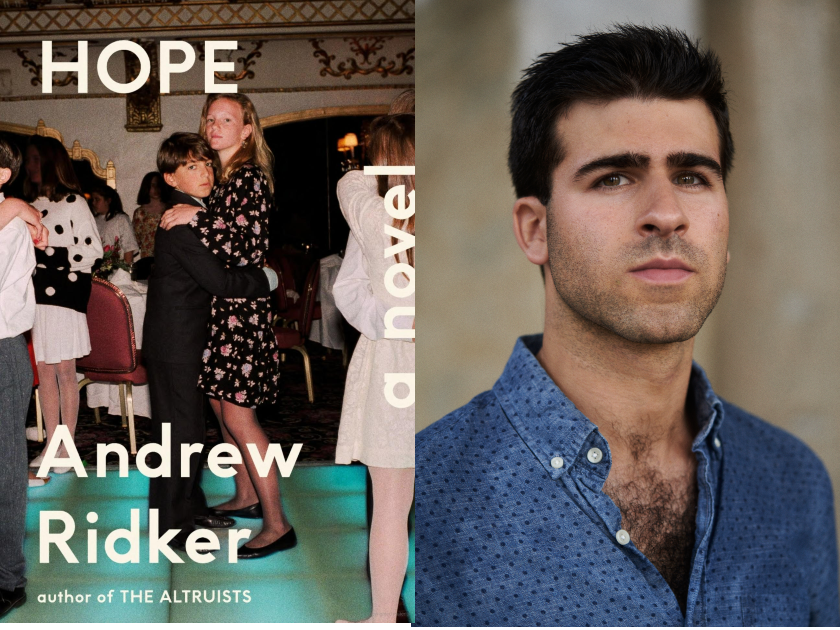

Author photo by Kyrre Kristoffersen

Benjamin Selesnick speaks with Andrew Ridker about his sophmore novel Hope. They explore the Jewishness of guilt, shifting family dynamics, and American Jewish privilege.

Benjamin Selesnick: Hope involves more conversations on Judaism and Jewish institutions than your previous novel, The Altruists. What compelled you towards this change? What role do you see Judaism playing in Hope?

Andrew Ridker: I’m tempted to say it’s a simple matter of geography. Hope is set in my hometown of Brookline, Massachusetts, which has something like eleven different synagogues. The Altruists is set in St. Louis, where you might have a hard time assembling a minyan.

But things are rarely so simple. In the four years that passed between the novels, I started thinking more about my Jewish identity. The subject began to feel more artistically fruitful. The novel I’m writing now leans even harder into the subject. At this rate, I’ll be Orthodox by 2025.

In Hope, I was particularly interested in the way that Jewish culture and history impose themselves on a modern, secular, American family. Their synagogue is not so much a place of worship as a site of social justice. Israel to them is less a holy land than a political (and sexual) battleground. I’m not passing judgment on these developments, but I think they are noteworthy.

BS: All of the Greenspans carry significant guilt — for unethical work practices, infidelity, their privilege, and trying to strike out on their own against the will or wants of the family. Can you speak to the centrality of guilt in the novel?

AR: Guilt is a very Jewish feeling. Maybe it’s the pressure that comes with being told we’re God’s chosen people. Maybe it’s our mothers. Whatever the cause, guilt plays a major role in my life, and in the lives of my characters, regardless of whether I (or they) have done something wrong.

That, to me, is the crux of the matter: the guilt is there no matter what. It’s one thing to feel guilty for cheating on a boyfriend or committing fraud, to cite two examples from the book. In those cases, guilt is not only appropriate, it may even be required. But feeling guilty about one’s privilege, or for going against the will of one’s family…these are murkier waters. There is a lot of drama in transgression, and it’s certainly fun to write, but my characters would probably feel guilty even if they led morally impeccable lives. I don’t know what it’s like to be any other way.

BS: Both Hope and The Altruists have characters, whose lives started in the suburbs, ultimately going overseas to more impoverished and war torn nations to try and find themselves and “do good.” What drew you to this topic and continues to interest you?

AR: Years ago, when I was applying to college, it was considered savvy to go on some kind of service trip to round out your resumé. One friend, I remember, went to build houses in the Dominican Republic. There’s nothing wrong with that on the face of it — service is service, however cynical the motivations — but it struck me as a particularly American phenomenon, this impulse to go to faraway places with the idea of “fixing” them. Growing up in the Bush era, it wasn’t hard to see the similarities between these kinds of trips and America’s misguided attempts to “spread democracy” in Iraq and Afghanistan.

In Hope, I initially set out to tackle Birthright. Something like 700,000 young Jews have gone on trips sponsored by that organization, and yet I’d never seen it dramatized in novel form. (Sarah Glidden has a great graphic memoir on the subject, How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less.) More and more, young people were walking off these trips in protest of the government’s treatment of Palestinians, or at least the one-sidedness of the tour agenda.

I was also reading about the Syrian Civil War, and the young American socialists — many from the suburbs, a number of them Jewish — who volunteered to fight on behalf of the Kurds. The podcaster Brace Belden is probably the best-known of these volunteer soldiers.

It’s no coincidence that left-leaning Jews were drawn to the cause. The Kurdish leader Abdullah Öcalan’s philosophy of Democratic Confederalism — which emphasizes direct democracy, environmentalism, feminism — chimes in many ways with the values I was raised on in my progressive Jewish suburb. In fact, Öcalan himself was influenced by a Jewish-American social theorist by the (fantastic) name of Murray Bookchin. I started thinking about how an unmoored young man like Gideon Greenspan might find his way from a planned and regimented Birthright trip to the chaos of a nearby war zone.

These misadventures abroad serve different functions in each book. In The Altruists, the patriarch, Arthur, goes to Zimbabwe with ostensibly good intentions, but he’s blinded by personal ambition and ends up causing a disaster. In Hope, Gideon goes to Syria with similar intentions and blind spots, but begins to suspect he’s not seeing action because an American is worth more to the cause alive than dead. He can’t escape his privilege, in the end. Even in Syria, he’s still a Greenspan.

Guilt is a very Jewish feeling. Maybe it’s the pressure that comes with being told we’re God’s chosen people. Maybe it’s our mothers.

BS: It’s rare to see parents in a family novel be in an open relationship, which Scott and Deb Greenspan are. What made you want to explore this type of relationship within the context of a family novel?

AR: A decade ago, I would have associated open marriages with key parties and other products of the sexual revolution. But in recent years, open marriages have become increasingly popular among couples (or throuples) of all generations and orientations. Even Bill de Blasio has one!

I was already writing about a couple, Scott and Deb, who see themselves as somewhat exceptional — and still haunted by desire. They have everything they could possibly want, but they want more. An open marriage, as a metaphor, seemed to fit this family: you get the stability of your long-term partner, plus the freedom to explore. At least, that’s the idea.

BS: Your wonderful sense of humor is one of the most striking aspects of both your novels. Do you have any comedic writers or other comedic artists that particularly inform your writing?

AR: Comedy has always played an enormous role in my life. On the literary side, I love writers who can make me laugh: John Kennedy Toole, Fran Ross, Lorrie Moore, Paul Beatty. But long before I was reading serious comic fiction — not the oxymoron it appears to be — I was watching Mel Brooks movies, listening to George Carlin albums, and watching Cheri Oteri on SNL. My sister, Elena, works in television, and the two of us have been writing comedy pilots and other scripts in recent years. There’s nothing more satisfying to me than getting a big laugh out of her.

BS: The stories of the four Greenspan’s are told in their own sections and in many ways play out in separation to the others. What brought you towards this structure? Did you discover it along the way or was it something you’d been considering before you wrote the novel?

AR: I had a sense from the beginning that I wanted the novel to be a kind of relay race, with each character carrying the baton for eighty or ninety pages before passing it on. That presented certain limitations, but I find limitations to be necessary, even helpful, when I’m starting a project. The story takes shape around those limitations. It seemed fitting that a book about a fractured family would be chopped up into isolated sections.

The idea was to keep the novel moving forward while allowing for those Rashomon moments, when a given event is seen from an opposing point of view. To me, that’s what it’s like to live in a family, when multiple or even contradictory truths can be found under a single roof.

BS: Maya and Gideon have particularly rocky relationships with the parent of their same gender: Maya resents Deb’s overbearing and moralistic stance towards her, and Gideon, long having stood in the footsteps of his father, is particularly rocked by the news of his father’s professional wrongdoings. Can you speak on these dynamics?

AR: I don’t want to speak in generalities, but in my experience, at least, the children of heterosexual partnerships tend to have more intense feelings about the parent of their same gender. I distinctly remember having a conversation with my sister some years ago when we realized that each of us were involved in these one-way psychodramas with our parents that broke down on gender lines. I don’t know that father-son or mother-daughter relationships are always rockier, but they seem more volatile, more competitive — more dramatic. Then again, Philip Roth and Sophocles might disagree.

BS: What are you currently reading and writing?

AR: I’m always reading novels, new and old. Some recent highlights: My Phantoms by Gwendoline Riley, Sons and Lovers by D.H. Lawrence, The Guest by Emma Cline, Of Human Bondage by Somerset Maugham, The Lost Weekend by Charles Jackson, The Vegan by Andrew Lipstein, The Tremor of Forgery by Patricia Highsmith, Orfeo by Richard Powers, Decent People by De’Shawn Winslow, The Family Carnovsky by I.J. Singer, Mr. Bridge by Evan Connell, Second Place by Rachel Cusk. I’ve been privileged to read two new novels by friends, Sanjena Sathian and Lee Cole, in manuscript. Keep your eyes peeled for those next year.

I’m working on an historical novel right now, so I’ve also been reading a lot of nonfiction for research. Apart from that, I like listening to biographies — Jonathan Eig’s new book on Martin Luther King, Jr. was a standout, as was Whittaker Chambers by Sam Tanenhaus.

Benjamin Selesnick is a psychotherapist in New Jersey. His writing has appeared in Barely South Review, Lunch Ticket, Tel Aviv Review of Books, and other publications. He holds an MFA in fiction from Rutgers University-Newark.