“Great Literature, Not-So-Great Fathers” originally appeared in a JBC email on June 14. Sign up here to be the first to read more content like this!

Father’s Day is here, so now is certainly not the time to consider the role of the father in Great Literature. No, no, no, we mustn’t, we can’t, we won’t, for today is the day we celebrate the father, his contributions to the family and the upbringing of the children and the life of the home, and if we were to go down the path of fatherhood in literature — in Great Literature — we wouldn’t find fathers worthy of much fanfare, nor praise, or even a good or word two. In fact, we’d find a strong argument that the fathers who make a person say, “This guy? Oh, my goodness. Terrible father. Just as bad as they come,” are exactly the thing that brings Great Literature to life. So I should stop here and pick another subject, shouldn’t I?

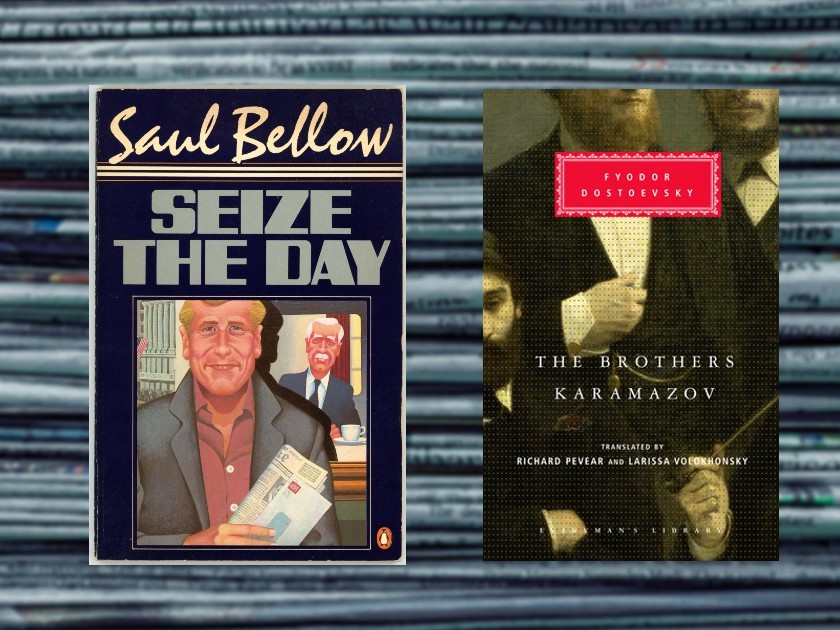

But having been asked to write something for the occasion: I just so happened to have recently reread two novels, Saul Bellow’s Seize the Day and Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Brothers Karamazov, in which some of the worst fathers in literature take center stage, driving their sons toward … well … in the case of Karamazov, patricide. (No, no, no, come on, we can’t write about fathers in Great Literature, not today, not for Father’s Day! It’s just not the time for it. And not a book about patricide. Come on!) What do these sons want from Dad? Oh, a kind word and a pat on the back would do. Maybe a check with a few zeros. Dmitry Karamazov would also ask that his father not romantically pursue the woman he is in love with, which seems like a request any father could submit to (although, these are very small towns in rural Russia in the 1800s that we’re speaking of, so who knows, maybe there just weren’t as many options out there).

Wilky, as well as the three Karamazov brothers, are pursuing their fathers because they want something from them, and their journeys … is the process of seeking and receiving, or not receiving, that thing: that is, the father’s love.

But above all else, the Karamazov Boys and Bellow’s Tommy Wilhelm would like Dad to give them a boost of confidence, perhaps a couple of boosts, the kind that would make a child believe that yes, in life, failure is inevitable but getting back up is the thing, and that Dad’s hand will be held out to you to help in the process, if not financially, than at least spiritually. Bellow’s and Dostoyevsky’s fathers, however, would rather that their children just go away, and both do everything in their power to make that happen. (Having two sons of my own, there are days when I can relate. But, come on, this is Father’s Day, and definitely not the day to talk about that. Hey, I love my sons! That’s the point.)

Bellow’s Dr. Adler and Dostoyevsky’s Fyodor Karamazov would make a contemporary day therapist say, “I think it’s time to put some real space between you and Dad. This relationship needs a pause.” But these sons keep moving toward Dad, closer and closer and closer. They go far out of their way to be near him. The son in Seize the Day has moved into the same Upper West Side residential hotel — based on the Ansonia on Broadway between 73rd and 74th — where his father resides. No one has forced Wilhelm to pick up and put himself smack in the middle of the same building as his father. Score one for Dad. What is the son doing there? Give Dad an inch!

Of course, Wilky, as well as the three Karamazov brothers, are pursuing their fathers because they want something from them, and their journeys — and the foundations of these novels — is the process of seeking and receiving, or not receiving, that thing: that is, the father’s love. (It is a favorite subject of my own, one I have covered in two of my four novels, Ark and Between the Records.) But these fathers can’t give it because they aren’t capable, are without the tools, the know-how, the stuff. And so what we have are two tragic father-novels, books you would never want to read on Father’s Day! (No, don’t do it. Maybe forgo reading any book at all with a father in it today!)

Or wait, maybe you would want to read these books on Father’s Day, for they will make you think of your own fathers, and might even bring you to say to yourself, “Hey, you know what, with Dad, I’ve had it pretty good. Yes, I have. I really have.” And being drawn toward appreciation and gratitude — in this case, of our own fathers — is the very spirit of this day. So, maybe Seize the Day and Brothers Karamazov are just the books to get into on June 16th, 2024. Enjoy, and happy Father’s Day!

Julian Tepper’s fourth novel, Cooler Heads, was published this past January. His writing has appeared in The Paris Review, Playboy, The Brooklyn Rail, Zyzzyva, The Daily Beast, Tablet Magazine, The New York Review of Architecture, and elsewhere. His essay “Locking Down with the Family You’ve Just Eviscerated in a Novel” was a Notable Essay of 2022 in The Best American Essays 2022. He was born and raised in New York City, and lives there still with his wife and two sons.