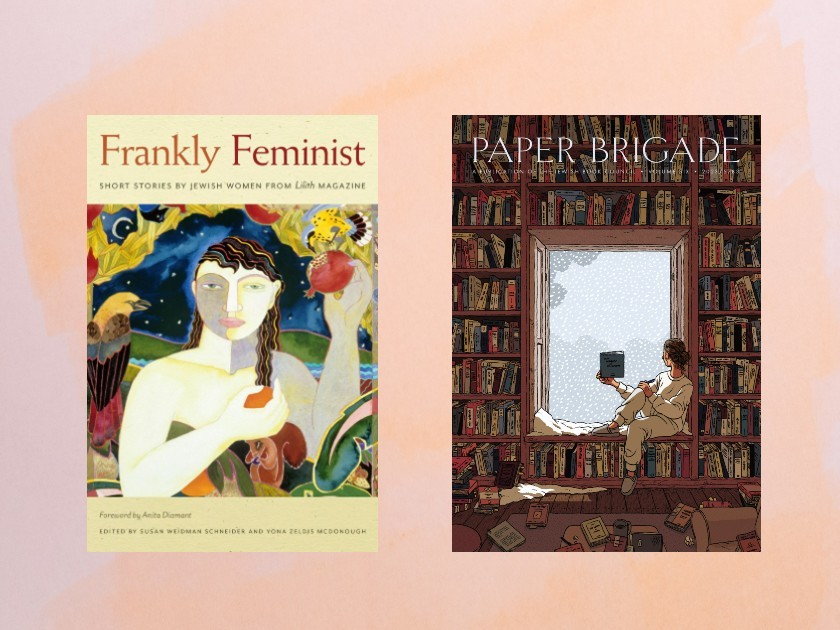

This fall marks the publication of both Frankly Feminist: Short Stories by Jewish Women from Lilith Magazine (edited by Susan Weidman Schneider and Yona Zeldis McDonough) and the sixth issue of Paper Brigade, the annual literary journal of Jewish Book Council (edited by Becca Kantor and Carol Kaufman). In celebration of the two publications’ release, the four editors come together to discuss the processes behind their work, what excites them about Jewish fiction today, and the books they can’t wait to read in the near future.

Yona and Susan, what was the impetus for creating Frankly Feminist?

Yona Zeldis McDonough: Susan and I share an enormous pride in the fiction that Lilith has and continues to publish. As fiction is whittled away from more and more publications, we have remained committed to publishing stories of the highest caliber from women of different ages, backgrounds, and affiliations. We both had a desire to create something more permanent and also to show, in one place, the wide range of the magazine’s vision.

Susan Weidman Schneider: There have been so many stunning original stories we’ve published in Lilith over the years, and authors we have discovered or nurtured, that the time was ripe for gathering a selection of them between the covers of a collection. This way, readers can enjoy them alongside one another, and enjoy the interplay of eras and attitudes.

What was the impetus for creating Paper Brigade?

Carol Kaufman: Since its beginnings, Jewish Book Council has produced a print publication — starting with Jewish Book Annual, which was published in English, Hebrew, and Yiddish, from 1942 to 1999. At that time we were also publishing a magazine, Jewish Book World—three, then four times a year — which consisted mainly of reviews. It covered a broad range of Jewish books and readers loved it. When we developed our website, we put the book reviews online so they’d be timely. That’s when Paper Brigade was conceived.

With Paper Brigade, we wanted to capture, between two covers, a sense of the remarkable array of Jewish-interest books with which we engage at JBC. We envisioned a beautifully produced annual print journal, composed mainly of original work — articles, short fiction, poetry, visual art, and interviews — along with excerpts from forthcoming books. We wanted it to be both timely and timeless, a keepsake.

How do you go about compiling each issue of Paper Brigade?

Becca Kantor: As Carol said, our aim with Paper Brigade is to celebrate the breadth and diversity of Jewish books today, both in the US and abroad. We try to accomplish this through a mixture of commissioned pieces and pieces submitted to us.

When the two of us sit down to plan the forthcoming issue, we start by commissioning work that explores overarching themes or trends that have emerged throughout the year. In this issue of the journal, for example, there’s an essay by Melissa R. Klapper, “Mothers and Others,” which examines three novels about infertility and the pressure on Jewish women to have children.

Interviews are another way of juxtaposing different authors’ work on similar topics. One interview in this issue is between Michael W. Twitty, the author of Koshersoul, and Shaunna J. Edwards and Alyson Richman, the coauthors of the novel The Thread Collectors. Although these books are in different genres, they both address the ways that the homemade – food and quilts, respectively – can be repositories of Black and Jewish history.

Through our Jewish literary map – which highlights a different country or region each year – and an excerpt of the work of our translation prize winner, we touch on the geographical diversity of Jewish literature. And through excerpts of visual arts books, we showcase the illustrators and artists who are an essential – and sometimes overlooked – part of Jewish books as well.

The fiction and most of the poetry we publish is submitted to us during our open submission period. For fiction, we have six excellent readers who help us make sure that each story is initially evaluated by two different readers, and then our fiction editor, Josh Rolnick, and Carol and I make the final decision as to which ones to accept.

What drew you to the two short stories published in this issue of Paper Brigade?

CK: “The Virgin Grandmother” appealed to us for many reasons: we admired Kate Schmier’s concise yet incisive way of describing her settings and her characters with a few well-chosen details. You feel you know these people, or people like them. But I think what really drew us to the story was its poignancy. You felt for the characters, and with them.

The main character is Frances, a proud, independent woman who has owned and operated an upscale stationery store since her divorce a number of years ago. The story concerns Frances’s relationship with Sol, with whom Frances and her ex-husband were friendly when they were married. Sol is now a widower, and lonely. You’ll have to read the story to find out what happens!

Laura Junger, a Parisian artist based in Berlin, has illustrated all of our original fiction in Paper Brigade, and, we think, nails it every time. The illustration for this piece gets right to the heart of Frances. She tells herself that she prefers being alone, and Laura’s painting places her, alone, in her riotously colorful bedroom, starring her favorite color, Revlon Red. Frances’s bedroom is not actually in the story itself but is Laura’s vision, and is in contrast with Frances’s facial expression, rendered in a few spare lines, that communicates — what? Wistfulness, loneliness, second thoughts?

BK: “Poland Itinerary, Class 3b” by Leeor Ohayon is an incisive portrayal of the way Ashkenormative retellings of history can exclude Mizrahi Jews by placing the Holocaust at the center of Jewish identity. In the story, a group of Brtish Jewish high school students go on a Holocaust remembrance trip to Poland. The protagonist, Daniel Amar, is one of the few Mizrahi kids in his class. It’s clear that the teachers and most of the other students feel that because his family didn’t directly experience the Holocaust, Daniel doesn’t really belong – he’s somehow less of a Jew than they are.

The narrative is structured as an itinerary, which reinforces the fact that there are assumptions and goals underlying the trip – whether that’s the teachers’ belief that the students will come to understand their grandparents better, or the students’ bets on who will be the first among them to cry. Leeor implicitly asks the reader to question those assumptions. What happens if your grandparents didn’t experience the Holocaust? What happens if you desperately want to cry like everyone else but can’t?

We found this story deeply thought-provoking in the way that it juxtaposes the Holocaust with a portrayal of prejudice within a contemporary Jewish community. It also cleverly aknowledges the challenge of writing fresh fiction about the Holocaust – the plot hinges on the fact that we’ve all read so many Holocaust stories, and seen so many movies, that it’s hard to think beyond the expectations we’ve formed from those iconic narratives.

Susan and Yona, how did you go about compiling Frankly Feminist from such a rich trove of pieces?

SWS: First, of course, we went back and read through the hundreds of short stories in Lilith’s back issues. And then we selected based on voices, subject matter, and – in the end – how the stories related to one another. As the themes of the book started to emerge, we found that some stories coalesced, some felt like different takes on related subjects. Each section features a brief introduction that highlights the intellectual content of the grouping to follow: Transgressions, Intimacies, Body and Soul, War, To Belong, and so on. It was actually an organic process as we paid close attention to perspectives, and voices. And we found that those voices represented wildly different eras and attitudes even as they conversed with one another.

YZM: We read through all the stories we had ever published — forty-five years’ worth! From that, we came up with a preliminary list of about eighty stories, which had to be winnowed down still more. It was hard letting some of our favorites go; there is definitely enough work for a second volume!

Was there anything that you found surprising or unexpected in creating this anthology?

YZM: Not as much surprising or unexpected as deeply validating. I always knew that we published great work, but seeing it altogether, as part of a larger pattern or tapestry, was so satisfying.

SWS: I was astonished at how much pleasure I took in reading and rereading the stories we’ve compiled – and of course we read each one many times. The book is (I say in all modesty, since I myself am not a writer of fiction) an absolutely wonderful read! The stories by bold, creative women are also about female characters who often see their worlds in sidelong, unexpected ways. Feminist for sure, and always surprising.

BK: I always learn new things as we put an issue of Paper Brigade together – it’s one of the things I find endlessly fascinating about my job! This year, I learned a bit about the history and culture of Indian Jews while doing research for our Jewish literary map of India. GennaRose Nethercott’s essay about the history of Jewish puppetry was fascinating to me. And I’m continually intrigued by the ways in which writers are reimagining creatures from Jewish folklore through a modern-day lens — whether that’s to explore sexuality, disability, race, or contemporary politics.

Have you noticed shifts or trends in Jewish fiction over the years? What, if anything, has remained constant?

SWS: The fine quality of the stories Lilith publishes remains constant, and has throughout the magazine’s robust forty-six-year history. Some of the characterizations would have been fantasy in the past (female spiritual leaders in all streams of Jewish life, for example. But other themes are ripped from today’s headlines: Abortion, autonomy over our own bodies. Discordant marriages. Challenging family relationships. Dislocations of war.

YZM: We used to get more stories about bubbies from the old world — the classic Jewish grandmother with her chicken soup, her Shabbos candles, her resilience and her grit. I’d say there are fewer of those stories now. The new thinking about and understanding of gender, as well as the willingness to understand gender in more than just binary terms, is something we are seeing more of lately. What remains constant is the high quality of the submissions we receive — there are always stories that manage to surprise and delight me and those that fill me with reverence and even awe.

BK: Yona, I completely agree about that shift. I’m personally most intrigued by stories that explore the crossover of different aspects of identity, and I think publishers have become more willing to take on this type of story, too. When we consider books for review on Paper Brigade’s digital arm, PB Daily, we’re sometimes brought back to the question “What is a Jewish book?” In the past, this might have been easier to answer. Jews were less integrated into mainstream society, so if a novel featured Jewish characters, Jewish identity would almost by default have to play an integral role in the plot. Now things are different. Take a novel like Gabrielle Zevin’s Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow. Two of the characters have Ashkenazi heritage and that does affect their lives, but so do race, privilege, illness, and death. And the true focus of the book is the characters’ relationships and the video games they create. It’s important to embrace novels like this, which have a relatively minor amount of Jewish content, as “Jewish books” because they are accurate representations of the Jewish experience of many people today.

That having been said, the recent rise in antisemitism in the US has certainly inspired a number of nonfiction books that address that issue head-on. I wonder if we’ll also be seeing more authors return to writing fiction that focuses primarily on Jewish identity or antisemitism.

What do you hope readers will take away from your publication?

YZM: I hope readers find stories that resonate for them, either by illuminating lives very different from their own, or by articulating aspects of their own experience that they had not yet put into words.

SWS: The wide range of voices and experiences in Frankly Feminist testifies to the richness in Jewish life and at the same time demonstrates the power of what women share within those differences.

CK: Mostly, I hope readers enjoy it and discover authors that intrigue and engage them. I hope they’ll be moved to read some of the books they’ve read about in Paper Brigade—and to gift the journal to book-loving friends and family!

What are you reading now and what are you looking forward to reading?

BK: Windstill, the debut novel of a dear friend of mine, Eluned Gramich, just came out in the UK, and I’m now reading it for the second time. In the book, a Welsh student goes to Germany to stay with her grandmother, who tells and retells her experiences of World War II in increasingly erratic ways. As the protagonist tries to untangle the truth about her family history, she’s also forced to confront a painful, and much more recent, memory of her own. This novel is a brilliant and nuanced meditation on how we’re often compelled to reshape our memories – to forget both our own trauma and the wrongs we’ve inflicted on others.

There are so many books I can’t wait to read next, but I’ll stick with the Germany theme and mention just one: De-Integrate! A Jewish Survival Guide for the 21st Century by Max Czollek. This book originally came out in Germany in 2018, and an English translation will be published by Restless Books in January.

CK: Lately I’ve been reading the Italian Holocaust-era writer Natalia Ginsburg; two books that stand out for me are her novel The Road to the City and the essay collection The Little Virtues. I’m looking forward to reading Gabrielle Zevin’s novel Becca mentioned: Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, which centers on a group of smart young video game creators. I’m also interested in reading works by Miron C. Izakson that have been translated into English. An excerpt from his novel Furthermore won this year’s Paper Brigade translation award.

SWS: I read very widely. Right now on my desk: the catalog of an Anni Albers textile exhibition; Worn: A People’s History of Clothing by Sofi Thanhauser; Nine Quarters of Jerusalem: A New Biography of the Old City by Matthew Teller, and the latest novel from Kitty Zeldis, The Dressmakers of Prospect Heights. Funny that three out of these four are about clothing or fabrics. So I should add that I have also been reading about the history of tuberculosis and Yiddish.

YZM: I’m reading the new translation of Colette’s Cheri and The Last of Cheri; I read all of her Claudine books when I was a young woman and now I’m finding it interesting to see how Colette portrays an older woman. I also just finished Maira Kalman’s Women Holding Things. The easy charm of this book in no way diminishes its depth. As for what I’ll be reading next, I don’t know! I don’t make lists of books I plan to read; I’m more like a bee buzzing happily in a garden, drawn to whatever appeals at the moment.