Ben Schachter is the author of Image, Action, and Idea in Contemporary Jewish Art, published in November by Penn State University Press. He is blogging here all week as part of JBC’s Visiting Scribe series.

I am a Jewish artist who makes Jewish art. Sounds redundant, no? It isn’t. Many artists are Jewish, but many fewer make art with Jewish subject matter. That is why I enjoy looking at artworks with Jewish ideas. Here is a list of my top five Jewish artworks. But they are just a start. There is a lot of terrific, engaging, perplexing and surprising Jewish art out there.

1. Helene Aylon’s The Liberation of G‑d 1990 – 1996

Aylon read through the Bible and highlighted every gendered reference to God. Her work has garnered her attention of feminist artists. Instead of defacing the text, Aylon laid transparent parchment over the text and highlighted words through it. Why do I like this work so much? Because it balances contemporary art’s use of monotonous activities with sensitivity to tradition. Aylon does not destroy, she illuminates.

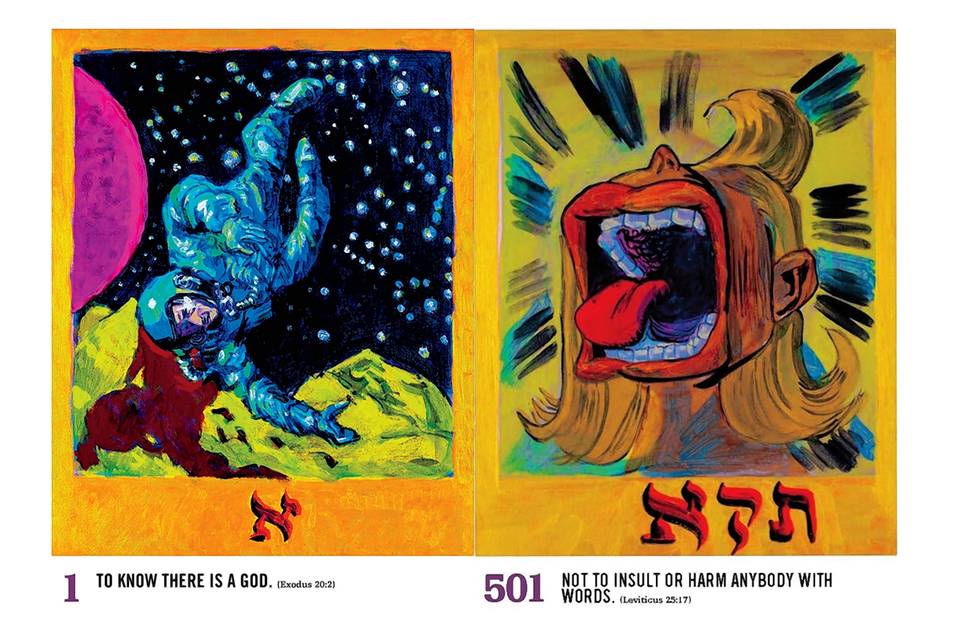

2. Archie Rand, The 613 2001 – 2006

Archie Rand’s monumental painting, The 613, just finished a run at the Contemporary Jewish Museum in Los Angeles. The painting is made up of over six hundred panels. Each panel is numbered, in Hebrew, with a colorful image inspired by film noir and pulp fiction illustrations. The number on each panel corresponds to each one of the 613 mitzvot, or commandments outlined by Moses Maimonides, the medieval philosopher and doctor. Rand’s images do not directly illustrate commandments, but at times the connection is clear as we see an astronaut floating in space as the numeral reminds us of the first commandment, “I am god.” I imagine the astronaut having a spiritual experience of the divine at that moment. Rand’s massive painting is great because it is unabashedly about Jewish law. There is no embarrassment over the old question, “Is this too Jewish?”

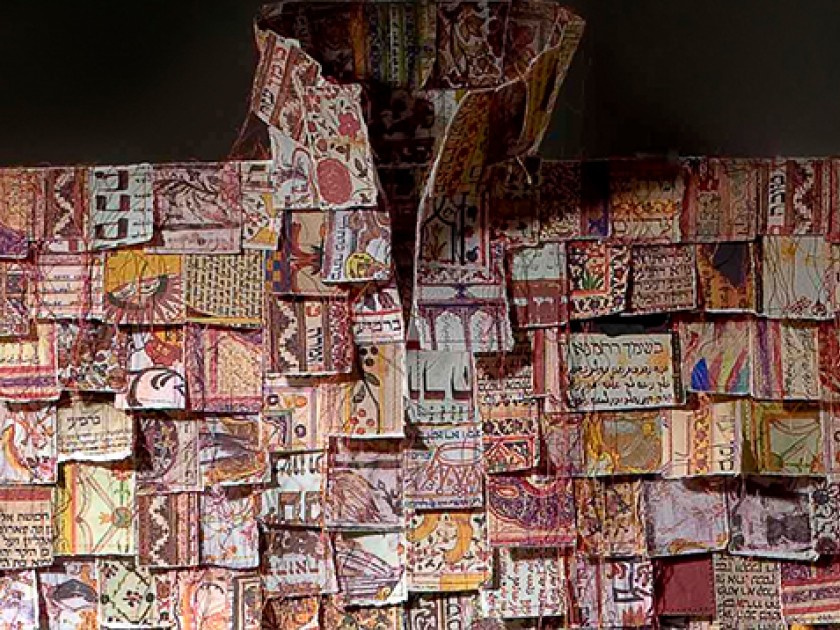

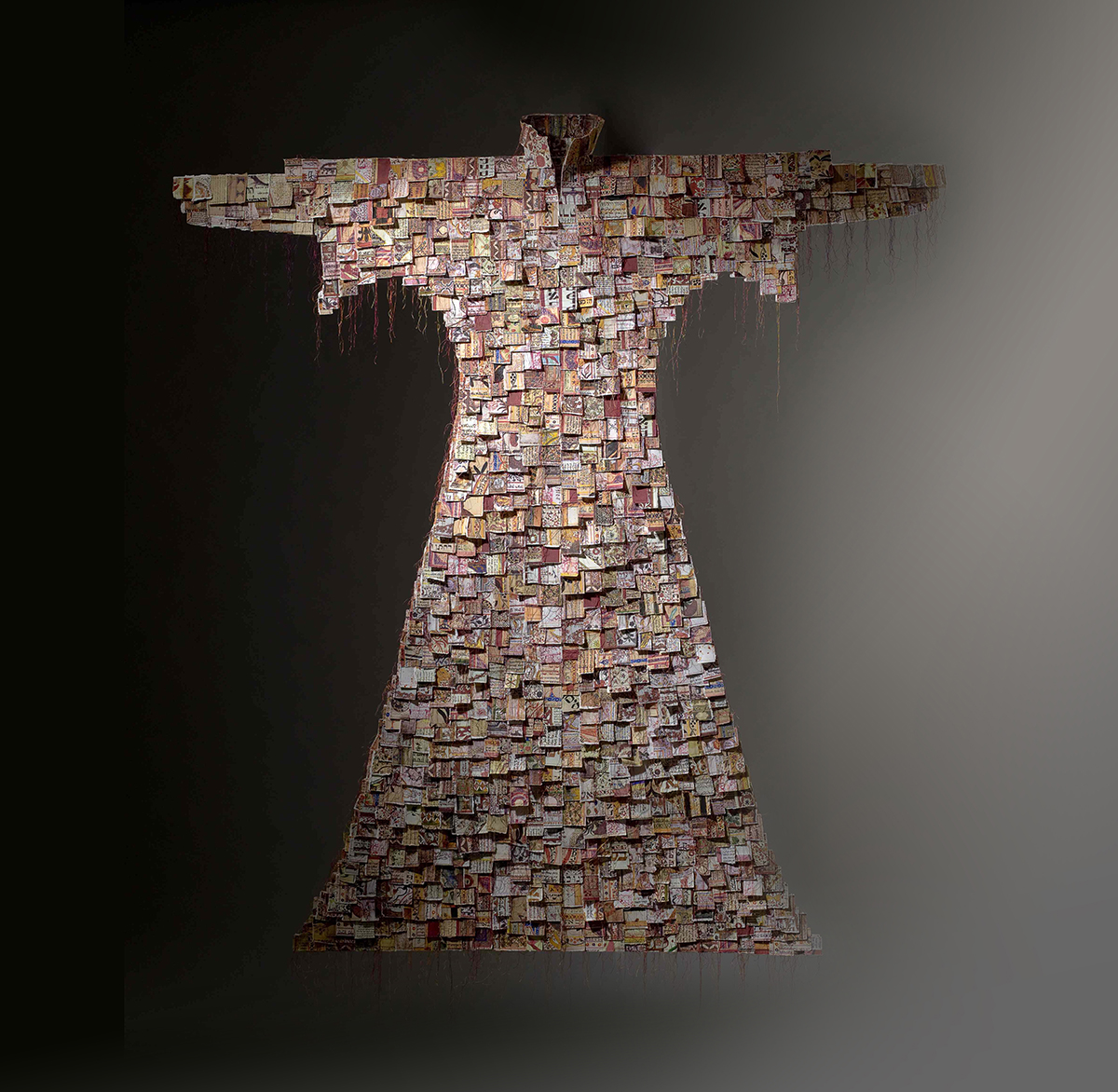

3. Andi Arnovitz, Coat of the Agunot 2010

Images courtesy of Andi Arnovitz

Andi Arnovitz emigrated to Israel and like Aylon, examines ideas important to women. One such issue is the plight of the agunah, a woman who wishes to divorce her husband but can not because he will not grant permission. Traditional Jewish law requires that the husband offer his wife a get, a legal document agreeing to divorce. No one enters a marriage with hopes of a divorce, a potentially baleful situation, but when there is cause and the woman cannot be freed from the marriage contact, she is thought of as a “chained woman.” When a divorce is finalized it is customary to cut up the marriage contract. Arnovitz’s work, Coat of the Agunot, is a patchwork quilt of facsimiles of historical ketubot (Jewish marriage certificates). The new garment is beautiful and also bittersweet. Arnovitz’s work is very touching.

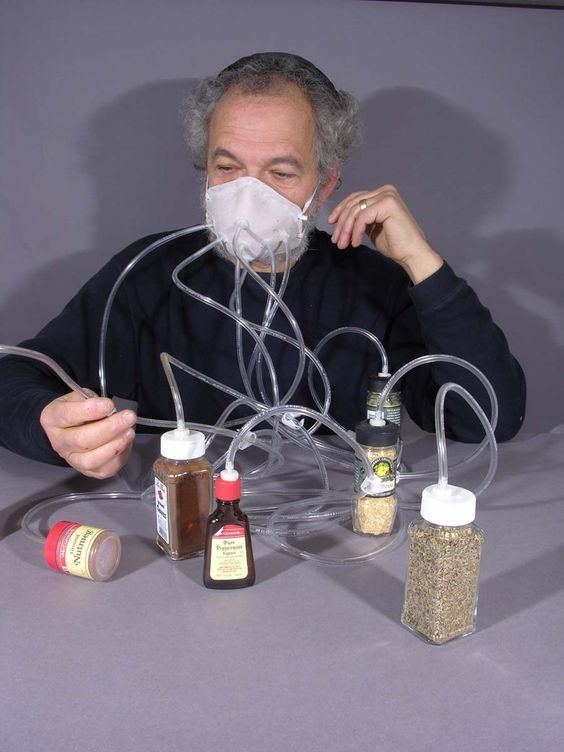

4. Allan Wexler, Spice Box for the Havdalah Service 2005

Image courtesy of Allan Wexler

Allan Wexler is an architect by training but his designs are rarely 100% practical. He designs rooms that are so small that furniture must be tucked away into small cabinets, doors are swung open and become walls, and windows pull out of their openings and become chairs. Spice Box for Havadalah is a similarly odd contraption. During the havdalah service, a brief ritual held at the end of the Sabbath, participants pay attention to the physical world around them. They do this in a few ways. First, they look at the light of a candle and second, they smell incense. Typically incense is kept in a small house-shaped container. Wexler’s spice box is nothing like that. His has a face mask, plastic hoses and store-bought spice bottles. The aroma travels from the bottles, through the hoses, and directly to the person wearing the mask. I find this work very funny.

5. Ken Goldman, With Without 2011

Image courtesy of Ken Goldman

Ken Goldman describes his work as performance art. With Without is a passive performance whereby he shaved his head except for a circular patch at the top. A casual observer might think he was wearing a kippah. And that is exactly his point. With Without is a photograph of the artist taken from just over his left shoulder. The photograph shows the “hair-kippah.”

Ben Schachter is the author of Image, Action, and Idea in Contemporary Jewish Art(Penn State University Press). He is Professor of Fine Arts at Saint Vincent College. In the past, he received the Hadassah Brandeis research award. His artwork has been exhibited at Yale University, YU Museum, the Jewish Museum, the Westmoreland Museum of American Art, the Mattress Factory, and other venues. His writing on art and criticism has appeared in various art journals and books, includingDrawing in the 21st Century, edited by Elizabeth Pergam andIt’s A Thin Line, edited by Rabbi Adam Mintz. He lives in Pittsburgh with his wife and four children.