Design by Katherine Messenger

Spanning the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first, Michael Zapata’s powerful yet whimsical debut is a testament to literature’s ability to transcend genre, gender, religion, and race.

After her parents are killed by American Marines in 1916, Adana Moreau leaves the Dominican Republic for New Orleans — where she eventually writes a much-lauded work of science fiction, Lost City. In 2005 Chicago, Saul, an Israeli immigrant, comes into possession of the book’s unpublished sequel.

As past and present converge, Zapata paints a portrait of an America filled with refugees — from pogroms, invasions, and natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina — who share a legacy of exile. He also shows how their lost worlds can be bridged through stories, which form immutable bonds between the tellers.

This excerpt, featured in the 2020/2021 issue of Paper Brigade, is set in the 1930s and portrays one such friendship. When Adana’s thirteen-year-old son, Maxwell, makes his way to Chicago, he meets a Jewish boy who promises to help him find his father.

I don’t know what I’m doing here, Maxwell said to himself after he’d been searching for his father in the market for two weeks. He said it at night in the alley next to the Jonava while trying to fall asleep on the piece of cardboard. But by then he had already twice seen the Jewish boy who had told him not to leave the city yet.

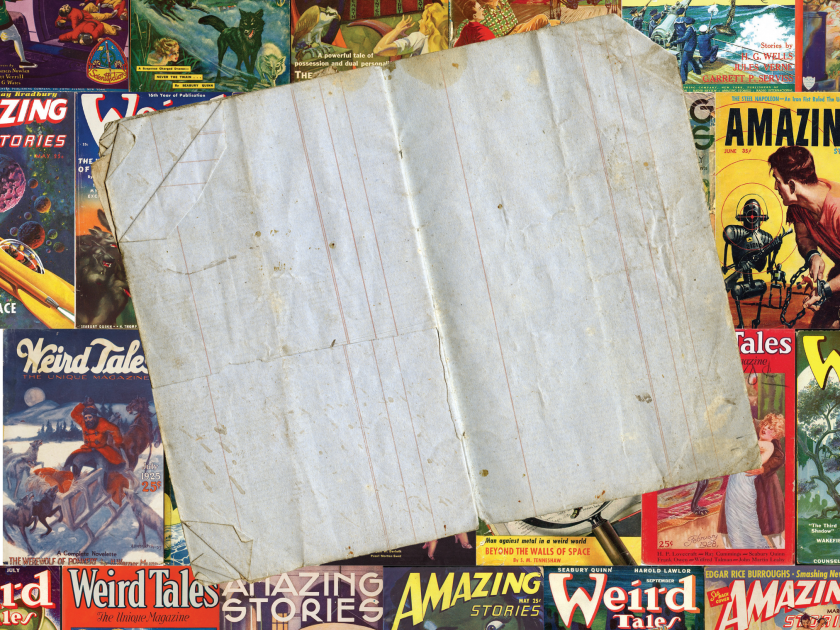

The first time was during a particularly cool morning when Maxwell was looking through an old geometry textbook at a bookstall. The Jewish boy, who was a full head shorter than Maxwell and who had black curly hair and long wiry arms, was inspecting a milk crate full of old magazines and talking confidently to the owner in a guttural foreign language. Then, for some reason unclear to Maxwell, the Jewish boy turned to him, smiled (an awkward electric shock of a smile), and told him in English he was having a hell of time that day looking for werewolf stories in old issues of Weird Tales. He’d already been to three other bookstalls that morning, to no avail. The first one he had ever read was a novella entitled The Werewolf of Ponkert by H. Warner Munn in the July 1925 issue, and this led him to the short story The Werewolf of St. Bonnot by Seabury Quinn in the May-July 1924 issue.

Some months later, in the April 1926 issue, he found an unexpected werewolf story by C. Franklin Miller entitled Things That Are God’s. Then, following this logic, he also found The Wolf-Woman by Bassett Morgan in the September 1927 issue. After scanning a few more issues in reference to both werewolves and women, he realized with some melancholy that he had come full circle, more or less, with The Werewolf’s Daughter by H. Warner Munn, a novel in entirety spanning three issues in 1928, from October to December. The year 1929, he observed, was suspiciously absent of werewolves, and he suspected that this had something to do with the pale and predatory men of Wall Street who had caused the Panic and were probably werewolves themselves and now trying to hide the fact, but he didn’t have proof, at least not yet.

After the boy stopped talking, he let out a deep sigh of resignation, waved goodbye to the shop owner and Maxwell, who was by then a little stunned, and left.

The second time Maxwell saw the Jewish boy was a few days later, when he went to a grocer on West 14th Street to look for his father. It was getting dark, but Maxwell could still make him out standing under the globular lights of a delicatessen next door. He was wearing a large sandwich board with the words Only the Best on the Planet.

When he saw Maxwell, the boy waved him over. Then he took off the sandwich board and took out a cigarette to share with him. Since Maxwell didn’t know what to say, he nodded and took the cigarette. The boy smiled and, without skipping a beat from a few days earlier, started to explain that since the last time they’d seen each other he’d visited the editorial offices of Weird Tales on 840 North Michigan Avenue, where none other than Mr. Wright, the editor of Weird Tales, had told him that there was a very good reason for the omission of werewolves in the 1929 issues, a reason he couldn’t just tell anybody off the street, but one that could still in all likelihood be rooted out from a dime novel published that same year called The Werewolf of New York City by Margaret Bok.

It was a blood-soaked and uncanny dime novel that had taken him nearly two days to find, if only four hours to read, and which was about a solitary wealthy banker who, at night when the moon was bright and full, metamorphosed into a werewolf and prowled tenement buildings of the Lower East Side looking for unsuspecting, newly immigrated, and impoverished victims, all of which not only proved his theory correct but also gave an entirely new historical significance to the Panic of 1929.

“I don’t believe in conspiracies all the time, Joe,” he said, “but I had to tell someone.”

Maxwell and the boy passed the cigarette back and forth.

“So, Joe,” he said, “what brings you here? You need any more math books?”

Maxwell told the boy that he was looking for his father. “I was supposed to meet him at the Jonava, but I don’t where he is,” he said. Then he added: “I think I’m going to go home.”

“Where’s home?” the boy asked.

“New Orleans.”

The boy took one final drag of the cigarette before snuffing it out on the curb. He then put the cigarette butt in his front right pocket. “Shit, Joe, don’t leave just yet,” he said, finally, “I’ll help you look for him. Meet me at the bookstand tomorrow morning.”

Then they said goodbye, but not without first introducing themselves:

“My name is Benjamin Drower,” the boy said, “what’s yours?”

He told him it was Maxwell Moreau, after which the boy said, “Like the market and the doctor. Got it.” They shook hands and went their separate ways.

All of this Maxwell recalled as he tossed and turned on the piece of cardboard in the alley next to the Jonava, unable to sleep. What was it about the boy that made Maxwell tell him about his father? Was it his short height, his vague foreignness, the fact that, unlike anybody else in the market, he had talked to Maxwell, or even the sudden impression that, like an impossible perpetual motion machine, he had never stopped moving? And he wondered again: I don’t know what I’m doing here, should I return to New Orleans? is there an unopened letter from my father waiting for me there? would I even know him if I saw him again after all these years? Finally he grew tired of all the questions, and he focused instead on the unequivocal shapes of a geometry problem floating like dust under his closed eyelids, and fell asleep.

By the time Maxwell went to the bookstand the following morning, Benjamin was already there waiting for him. Wandering the market, they questioned vendors like detectives. Had they met a man named Titus Moreau from New Orleans? they asked. Had they met anybody staying at the Jonava looking for work? Had they seen a man writing letters or reading the sky? Had they heard any rumors about someone called the Last Pirate of the New World? Etc. etc. To which some of the vendors looked askance, and to which others simply said, “Some men might have a name like that,” or “Lots of men from the South here,” or “Lots of people from everywhere here.”

In any case, the vendors, many of whom Benjamin knew personally, knew nothing. Two or three times, he fell into heated arguments with the vendors in the same guttural foreign language Maxwell had heard him speak earlier. Maxwell didn’t ask what language he and the vendors were speaking. But later, Benjamin explained to him, a little frustrated, that it was next to impossible that nobody in the market knew anything, but the problem was that the vendors thought and often spoke in Yiddish, a language that, at least according to his father, a tailor originally from Vitesbk, suffered from a sense of Weltschmerz, which was the melancholic suspicion that there was never enough knowledge or reality to go around.

Later still, as they sat on a curb in front of the delicatessen on West 14th Street, sharing a sticky bun Benjamin had purchased and watching the coral sunset as it swirled above the market stands, Benjamin asked Maxwell where he was staying.

“I was staying at the Catholic orphanage,” he said, “but I snuck out.”

“Why’d you sneak out?” asked Benjamin.

“They’re Catholics,” he said, “they wouldn’t let me leave.”

Benjamin laughed. Then he told Maxwell he had an idea.

“Follow me,” he said.

They hopped the metal bumper of a streetcar heading west and then another heading south. They passed through several neighborhoods and a park with worn-out tents surrounding a steadily burning fire in a steel drum. Some minutes later, they hopped off the streetcar and walked a few blocks west until they reached a limestone building. Out front, a group of older boys stood talking with two middle-aged men wearing black suits and black hats, one of whom, Benjamin whispered to Maxwell, was his rabbi. As they walked by, an obstinate silence descended inexplicably over the quartet.

They entered the limestone building and climbed five flights of stairs until they reached a locked door to the roof. Benjamin took out a key and opened it, and they walked outside. The sky was black and the lights of the endless city were like thousands of incandescent anemones floating on the surface of a black sea. At the far end of the roof stood a small storage shed. Inside was a bookshelf, lined with dime novels and old issues of Amazing Stories and Weird Tales, and a single, spotless cot in the center. On the cot was a wool blanket, a flashlight, and a black skullcap, which Benjamin picked up and put in his back pocket.

“Sometimes, when I want to get away to think or read,” said Benjamin, smiling, “I come here. It’s a regular goddamn Babylon.”

________

In the mornings, after rye bread and coffee, Maxwell and Benjamin returned to the market to search for Maxwell’s father, but there was still no sign of him. They went to the police station, but the police were disinterested. One sluggish, pockmarked officer told the boys that everybody’s old man went missing at some point and then half-heartedly asked Maxwell a few questions and filled out a yellow form. Another officer just shrugged and told Maxwell that unless he was greatly mistaken, he would never see his father again.

Sometimes, as they searched, Maxwell felt feverish. He thought it was the overwhelming sense of aimlessness that made his body burn, but later he understood that the sensation was anger at his father for deserting him. Afterward, more often than not, they left the market and took El trains to neighborhoods that were vaguely reminiscent of foreign countries. At seven or eight, just before dusk, they’d take the streetcar back.

Sometimes, as they searched, Maxwell felt feverish. He thought it was the overwhelming sense of aimlessness that made his body burn, but later he understood that the sensation was anger at his father for deserting him.

On no few occasions, they ended their days on the rooftop, where they sat with their feet dangling over the ledge, sharing a half-smoked cigarette, fiddling with a cheap radio kit. Sometimes, with the air of failed detectives, they recounted the events of the day and the search for Maxwell’s father. Other times, Benjamin talked nonstop about the people who lived in his neighborhood, which he had nicknamed the Isle of Pale (after the now defunct Pale of Settlement in the also now defunct Russian Empire). He told Maxwell about the rabbi who ran a counterfeit synagogue; the young woman from a shtetl outside Kiev who had once walked from Kiev to Istanbul and who now never left her apartment building but could still be found every winter night, like a sleepwalker, on the rooftop across the street bundled in a black cloak playing a violin; the alderman who once walked the streets with the infamous anarchists Emma Goldman and Ben Reitman; the Orthodox grocer whose favorite thing to say in English was moderation in all things, including moderation, in short, about all those Jews for whom, according to Benjamin’s father, a paradox was everything.

Once, as even further illustration, Benjamin told Maxwell a joke that his father had told him. A poor man from Kaunas beseeched God every week for charity. Every week God listened to the man’s tales of woe and doled out gifts that, little by little, improved the man’s condition. One day, God, who was really quite busy during those troubled years, appeared and said to him, “Listen, you know I will continue to help you every week. You don’t have to convince me anymore. A little less cringing, a little less moaning, and we would both be happier.”

To which, matter-of-factly, the poor man said, “My good YHWH, I don’t teach you how to be a god, so please don’t teach me how to be a human.”

Maxwell enjoyed listening to Benjamin’s stories and, speaking truthfully, one might call him Maxwell’s first friend. Each day, it became a little harder for him to leave the city, and Maxwell spent more and more time with Benjamin, whether searching for his father in the huge market and its surrounding neighborhoods or smoking and talking on the rooftop overlooking the Isle of Pale.

Chance or fate or the old mad pirate’s Caribbean devil had it that Benjamin, too, was the first and only person Maxwell ever told about A Model Earth. One August day, while Maxwell was looking through Benjamin’s back issues of Amazing Stories and Weird Tales in the rooftop shed, he discovered the opening chapter of his mother’s novel Lost City in the June 1929, Vol. 13, No. 1 issue of Weird Tales. At first, since he hadn’t known anything about the excerpt, which was titled “The Dominicana,” he was taken by surprise, and since Benjamin was working that day at the delicatessen, he had no one with whom to share his surprise. Instead, he read the excerpt of his mother’s novel three times. Each time he wept.

Later, when Benjamin returned, he told him:

“My mother wrote this.”

Benjamin took the issue and read the name of the author.

“Adana Moreau is your mother?” he said with astonishment. Then, after a long pause, he added, “What a huge goddamn coincidence.”

To which Maxwell replied that there were no such things as coincidences and that rare things like this happened in the universe all the time.

“What rare things?” said Benjamin, even more perplexed.

As dusk fell and they shared a cigarette, they tried to decide which rare things could be mistaken for coincidences or vice versa and were unable to agree. Later that night, Benjamin told Maxwell that the only thing to do at that point was for him to read Lost City. Maxwell agreed that this was the best solution, and he lent Benjamin the copy he had brought with him from New Orleans.

The next morning, at the kitchen table, Benjamin told Maxwell that he hadn’t slept all night (or maybe he had slept a little and dreamed that he hadn’t, he couldn’t remember). He said it really didn’t matter if coincidences existed or not because Lost City was a great science fiction story. He stressed the word great. Maxwell said he didn’t know the difference between a great science fiction story or just a good one or even a terrible one. Benjamin said the difference lay in possibility, in the possibility of the story and the possibility of the language in which the story was told. Immediately he began to cite examples. He talked about Mary Shelley and H. P. Lovecraft, he talked about Yevgeny Zamyatin and E. E. “Doc” Smith, he raved about Aldous Huxley. He said he had read all those authors and that Adana Moreau was their equal or maybe, in some ways, she was even better. Then, naturally, he asked Maxwell if his mother had written anything else.

Maxwell said he didn’t know the difference between a great science fiction story or just a good one or even a terrible one. Benjamin said the difference lay in possibility, in the possibility of the story and the possibility of the language in which the story was told.

“Yes,” he said tentatively, “she wrote a sequel called A Model Earth, but she destroyed it in a fire just before she died.”

“Did you read it?” asked Benjamin.

“I did.”

“Can you tell me about it?” he asked with some hesitation.

For a few seconds Maxwell said nothing and only studied his face. Then he nodded.

As they wandered the market that day, which was plunged in frenetic late-summer activity, Maxwell told Benjamin the plot of A Model Earth from start to finish. What little he couldn’t remember, he made up. When he was finished, Benjamin started pacing the already overcrowded sidewalk in excitement.

“Is it good?” asked Maxwell over the din of the market.

Benjamin stopped dead in his tracks, looked Maxwell in the eyes, where he was certain there were still a few traces of A Model Earth to be told, and said, “You know the answer to that already, Joe. It’s better than good and you need to write it all down again. You have to finish the story.”

Maxwell thought about it for a moment and then shook his head.

“You have to understand. It’s still possible to get it all down. It has to exist again. Others need to read it.”

Just then, Maxwell saw his mother sitting at the kitchen table with a typewriter, her long coffee-colored hair forming the swirl of an Arabic numeral on her back as she bent her head down, her gaze fixed on the manuscript, typing to a rhythmic beat that matched his own heart, a small heart beating in the chaos of her final days.

“I can’t,” he said.

For several nights, Maxwell had terrible dreams in which time was reversed and his father was his son, and his grandfather was his grandson, and great-grandfather was his great-grandson, and so forth, through the entire line of his African pirate dynasty, until the end was the beginning.

Sometimes, to calm himself after he woke, he drew geometry problems from memory on a small notebook until he could fall back asleep. Other times, he woke shaking and was overcome by the irresistible urge to go outside and walk.

After another week with no leads, Saul pointed the boys to an article in the Daily Illustrated Times that he thought could help. The article was about a mother, who, in 1919, had gone to Paris in search of her son. He had joined the Allied troops in 1914, but disappeared shortly thereafter. The woman didn’t find her son. However, years later, while living in an apartment near the Maison de Victor Hugo in Paris, a soldier-turned-grocer who resembled her son, who had nearly the same high forehead and burning cobalt blue eyes, brought her a bag of vegetables. He had fought in the Austro-Hungarian ranks and had lost his mother during a British tank assault. In some ways, the woman he saw resembled his deceased mother. She had the same dark hazel eyes and nearly the same laugh, high-pitched and tender, a laugh that could be heard through the wheat fields of his small village as a child. Upon seeing the soldier, she laughed and called him son in French. Upon hearing the woman’s laugh, the soldier called her mother in Hungarian, and entered the apartment, which suddenly felt as familiar to him as the fiery green waters of the Danube.

“But how can this help us, tateh?” said Benjamin when his father was finished. “The people in this story are delusional.”

“It has nothing to do with delusion, Benjaminas,” said his father, “it has to do with forgetting, and then remembering.”

“Like an amnesiac? Still, this does not help us, tateh,” said Benjamin.

“Yes, it does,” his father said. “After I read the article, I went to the offices of the Daily Illustrated Times and convinced the reporter, a man who is clearly interested in missing people, to help us look for Maxwell’s father.”

“How did you convince him?” asked Maxwell.

“I told him your father is a pirate,” he said with a smile.

Michael Zapata is a founding editor of MAKE Literary Magazine. He is the recipient of an Illinois Arts Council Award for Fiction, the City of Chicago DCASE Individual Artist Program award and a Pushcart nomination. As an educator, he taught literature and writing in high schools servicing dropout students. He is a graduate of the University of Iowa and has lived in New Orleans, Italy and Ecuador. He currently lives in Chicago with his family.