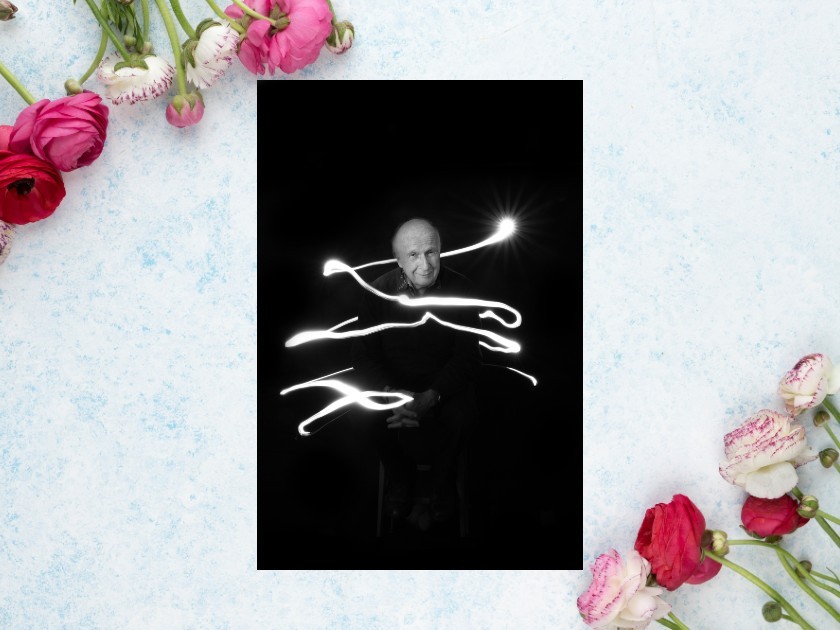

Photograph of Roald Hoffman courtesy of the author

Roald Hoffmann

He grew up in an attic. He didn’t start in one, of course; no one ever held a gleam in their eye imagining the child they’d one day raise in an attic. It wasn’t the plan. But then an invasion came, the latest in a series of endless wars, and the whole family ended up in a labor camp. A few bribes later, they were out, and Roald, he grew up in an attic, in hiding, cramped together with his mother, two uncles, and aunt above a small schoolhouse. Their father went back to the labor camp. He’s still there.

The family bought the papers of a dead German soldier to use for their escape, and Roald Safran became, forever, Roald Hoffmann. “There were racist quotas for immigrants and they were bizarre. More Germans were allowed in than Poles, so we made ourselves Germans. I think about this a lot, these days,” he recalls in his office at Cornell University, “because I think about the DREAMers. We snuck into America with stolen papers. We were illegals.”

He wanted to be a poet. Still does. His family wanted him to be a doctor. At Columbia, he sat in on humanities courses, especially literature. “In books, the world opened up for me. I worked up enough courage to tell them that I didn’t want to be a doctor, but not enough courage to tell them I wanted to be an art historian. I settled on chemistry.

The compromise has lasted: one suspects he no longer needs to, but after a few residencies and many research projects, he ended up as a professor at Cornell. Sure, he wanted to be an art historian, but he still teaches chemistry. He’s written three plays, but still he teaches chemistry. He hosted a program on PBS, but still he teaches chemistry. He’s written four books of poetry, but still he teaches chemistry.

And, yes, he won the Nobel prize, but he still teaches chemistry. He does all of it, after all these years, on a borrowed man’s name. “I still teach,” he says, “because I want to be a good boy.”

The plays, and the poetry, and the life of work, one can feel with no difficulty, all have their forewords written in his time in that attic. They all touch on his experience, but all look forward. Still, Professor Hoffmann just wants to be a good boy: in 2006, he brought his son to the small Ukrainian village where he was raised, to see how the old attic was doing. On arrival, they were told the attic is still above a schoolhouse.

They use it, of course, to teach chemistry.

Roald Hoffman

Photo courtesy of the author

Gitta Rosenzweig

In the dictionary, the word pacific is defined as peaceful in character; Gitten Rosenzweig lives in a pristine white building dangling over the Pacific, but you can tell that the woman, like the ocean below her, is anything but.

Life is complicated. People are complicated. Rescued by a woman from her village, hidden in a Catholic orphanage, and transplanted to a new country in the new world, Gitta is complicated: brilliant, and successful, and plagued with anxiety, and still thriving. School came easy, and she felt pulled by the dense gravity of the law- “something about justice I wanted to identity in myself,” she claims- but public speaking gave her panic attacks. Her accent gave her panic attacks. “Everything was scary: dealing with people, with clients, with relationships. I felt that I had to find something that I was comfortable with and wouldn’t have any anxiety from.”

The call for justice kept calling, until finally she answered in the only way she knew how, the only justice she knew: she became an immigration attorney. She loved the study of it- “the practice is the interaction with people,” she notes. “The law is the books, the ideas.” She devoted her life to the books. She devoted her life to the ideas.

In later life, she took her sons back to Poland, to see where she was from, where she had been hidden, from where she’d escaped. She found her birth certificate- proof that ever she had existed on paper. And her son met a local woman from the world Gitta had left behind. They married. Their daughter, who is four years old, is now here in the new world, dangling over the ocean with her grandmother. She sits quietly as we all talk, as her grandmother tells her story. Occasionally she looks up, occasionally she listens in, casually and without a care in the world. She is, it turns out, quite pacific.

Gitta Rosenzweig

Photo courtesy of the author

B.A. Van Sise is an author and photographic artist focused on the intersection between language and the visual image. He is the author of two monographs: the visual poetry anthology Children of Grass: A Portrait of American Poetry with Mary-Louise Parker, and Invited to Life: After the Holocaust with Neil Gaiman, Mayim Bialik, and Sabrina Orah Mark. He has previously been featured in solo exhibitions at the Center for Creative Photography, the Center for Jewish History and the Museum of Jewish Heritage, as well as in group exhibitions at the Peabody Essex Museum, the Museum of Photographic Arts, the Los Angeles Center of Photography and the Whitney Museum of American Art; a number of his portraits of American poets are in the permanent collection of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery.