Everyone called him “the child.”

Whether speaking in Yiddish or German, Herschel Grynszpan’s mother and father naturally spoke of their youngest as das Kind. When das Kind was fifteen, Sendel and Rivka Grynszpan (pronounced “Greenspan”) got their son out of Hitler’s reach by sending him to live in Paris, where his Uncle Abraham and Aunt Chawa called their rescued nephew l’enfant. Two years after that, as the French police hustled this diminutive threat to European peace through a gauntlet of blazing flashbulbs and swarming press, reporters noted that the boy assassin looked closer to thirteen than seventeen. Later, Herschel’s French lawyers — antifascists vaunted as the best legal minds in France — always referred to their young client as le petit. When she formed a legal defense fund to advocate for “the little one’s” essential (albeit not literal) innocence, Dorothy Thompson, then the foremost anti-Nazi journalist in the English language, called him “this boy.” Even Adolf Eichmann himself — after interrogating Herschel in Berlin with a view to the propaganda surrounding the Holocaust — referred to him as der Knabe: the lad.

—

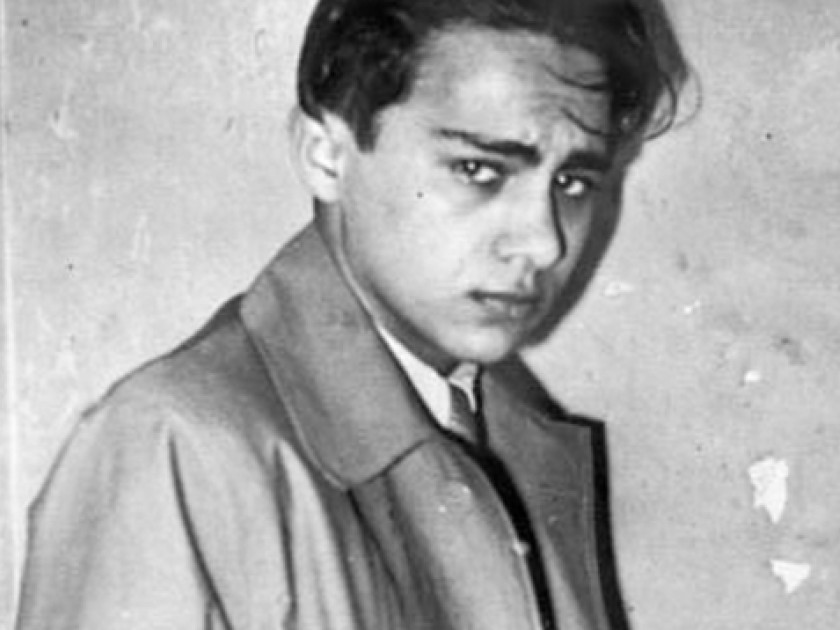

He was small, like many a pawn, and cursed with a baby face. He became famous on the cusp of maturity: In some photographs he looks like a frightened child; in others he is quite handsome, almost sultry, albeit in a boyish way. He had large, expressive, dark eyes and wore his black hair slicked back in the style of 1930s adolescence. He was frail. When he turned seventeen, he weighed just under a hundred pounds and stood a fraction of an inch taller than five feet one. His health was never good; as a child he may have had rickets. In early adolescence, there had been an appendectomy. Worst of all, he suffered from some sort of lifelong gastric problem — perhaps an ulcer — that was intermittently agonizing. Even in prison, he was a regular visitor to the infirmary.

He was clever with his hands and had a yen for sports; his main passion was for soccer, followed by Ping-Pong, which he played with the speed of an ace. According to most adults around him, he was “a gentle, self-effacing, obliging, and affectionate young man,” albeit moody. He may have been on the bipolar spectrum. He was subject to recurring depressions and sudden hot-blooded rages, even fistfights, on and off the soccer field.

But views of Herschel’s temperament vary. Among his contemporaries on the soccer field and at school, he was known as “the Hun king” because he was “dark-complected and very hot-tempered.” “Some who knew him in childhood remembered the boy as a quarreler.” Meanwhile, his brother, Mordecai, recalled his kid brother as a wit and a skilled and devastating mimic, whose imitations of pomposity could crack up a roomful of adults. There was something else: Both Mordecai and the lawyer who knew him best, Serge Weill-Goudchaux, used the same word to describe the boy. He was, they thought, fearless.

Herschel had grown up with Hitler’s consolidation of the Nazi tyranny. In 1933, when Hitler became chancellor, Herschel was eleven. In 1935, when the anti-Semitic Nuremberg Laws were passed, he was fourteen and a student learning Hebrew in a Zionist yeshiva in Frankfurt, hoping to emigrate to Israel. When he was fifteen, his family sent Herschel to Paris to escape an increasingly dangerous Reich. When Herschel was sixteen, Adolf Eichmann sent Hitler a memorandum arguing that mere legal persecution would never force Germany’s Jews to leave the country and surrender everything they possessed to the kleptocracy. Eichmann recommended more persuasive measures such as lawless mass terror: a nationwide pogrom. This proposal foreshadowed the Kristallnacht. When Herschel was seventeen, Hitler summarily deported more than eighteen thousand Polish Jews living in Germany — among them Herschel’s mother, father, sister, and brother — stole all their money and worldly goods, and dumped them, penniless, on the Polish border.

It was when Herschel heard about his family’s deportation that he decided what he had to do and acquired what he had never so much as touched before: a gun.

Excerpted from Hitler’s Pawn: The Boy Assassin and the Holocaust, copyright © 2019 by Stephen Koch. Reprinted by permission of Counterpoint Press.

Stephen Koch is the author of two novels and many books of nonfiction on subjects ranging from Andy Warhol to World War II. After serving as chairman of the Creative Writing Division in the School of the Arts at Columbia University he wrote a classic text on writing, The Modern Library Writers’ Workshop. The director of the Peter Hujar Archive he lives with his wife in New York and has one daughter.