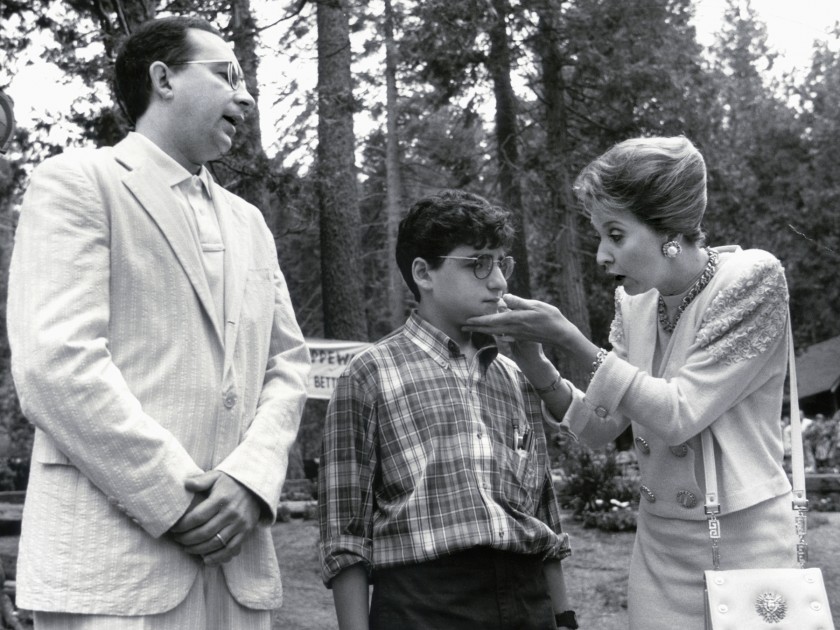

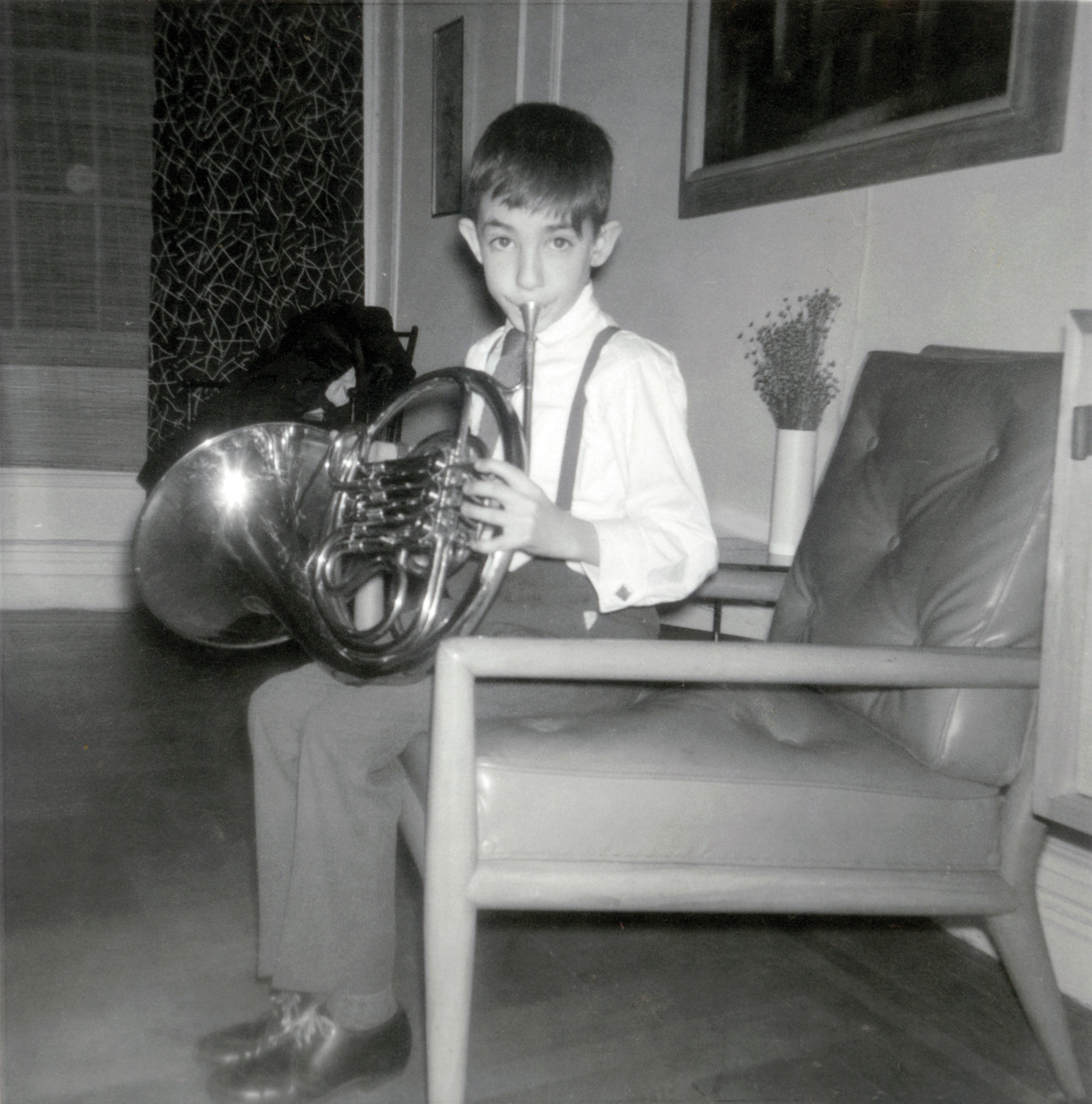

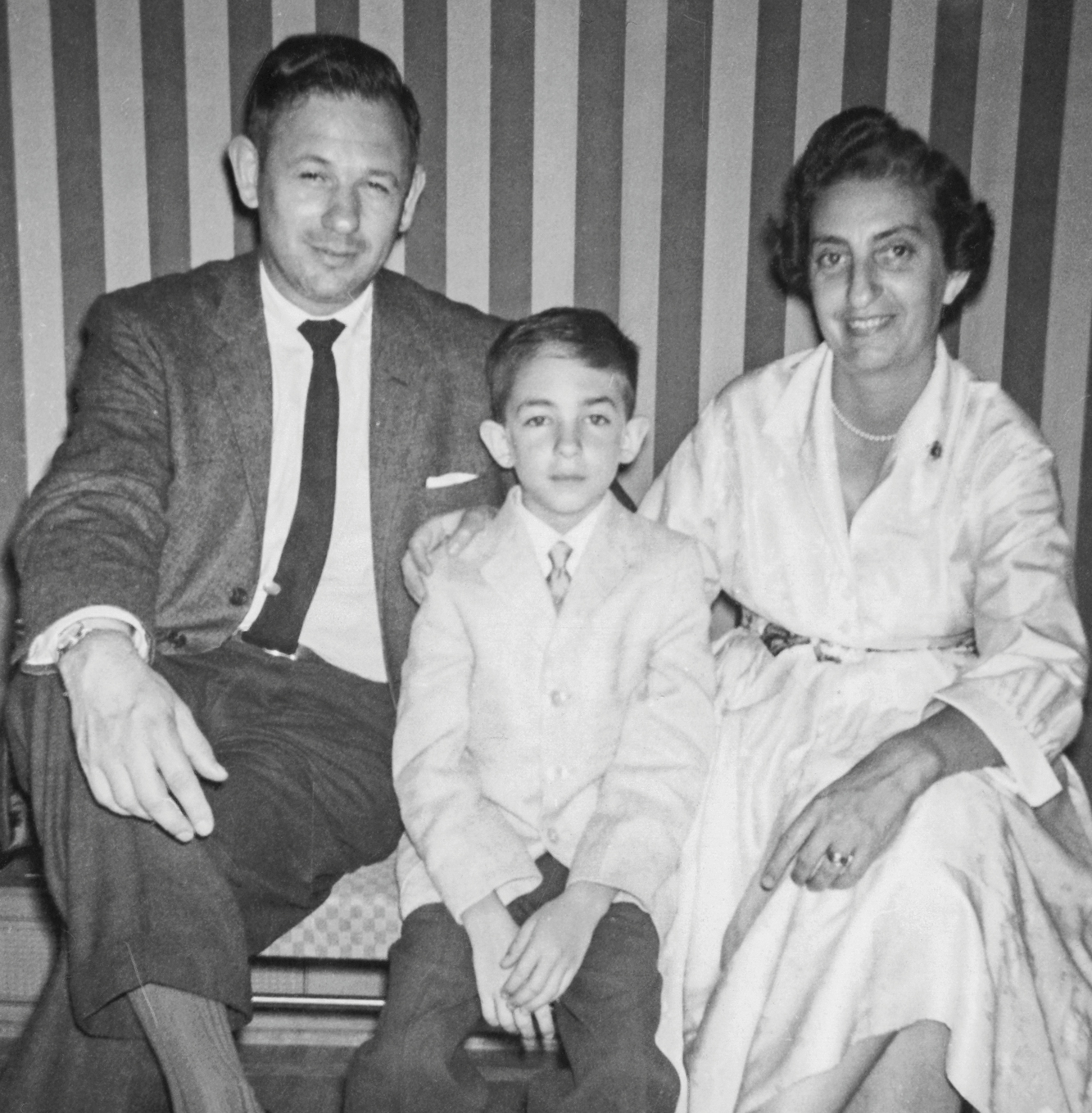

Me, David Krumholtz as young me, and Julie Halston playing young me’s mother. Addams Family Values (1993). All images courtesy of the author.

CHAPTER 8: A VERY SPECIAL BAR MITZVAH

Every Monday and Wednesday afternoon, from three to six, between the time I was 11 until two weeks before my April 2nd Bar Mitzvah at the age of 13, I was at Kenny Morrison’s apartment.

Kenny never wondered why I was hanging out with him after school on those two weekdays, instead of with the kids in my building. That was until one afternoon when Kenny and I were huddled together in his bedroom, sneaking peeks at his father’s Playboy. The door opened and, unannounced, my father, who had never left work this early except the day he passed a kidney stone, looked down at me and said, “Come on, Barry. Let’s go.”

For almost two solid years I had been playing hooky from Hebrew school.

There are three levels of Jewish tribes: Reformed, Conservative, and Orthodox. My father was raised Orthodox. One of seven children, he was Kosher until he was drafted. My mother was raised as a conservative, although she never practiced. I was a cultural Jew, not a religious one, having no interest in what seemed to be a petty, vindictive, and insecure old testament God.

In my case, what made Judaism particularly painful was that Hebrew school was taught twice a week by Rabbi Baulmal, a bald man with a huge black wart below his left nostril. He was also blessed by God with baggy eyes and a bird’s nest coming out of his nose and each ear. He looked more French bulldog than Rabbi.

Hebrew School met in a windowless room in the basement of Temple Beth Shalom. The Rabbi smoked white owl cigars in a ventilation-free fire trap surrounded by kids under the age of 13. We learned how to read the Hebrew alphabet and to phonetically speak the words. We didn’t study what any of the words meant. When I say we, I mean everyone who didn’t play hooky for two years. I couldn’t stand it. Couldn’t take the smell or tedium.

Three times a year my father and I went to Shul: Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, and Passover. Yom Kippur is the holiday that Jews fast for twenty-four hours — from sunset to sunset. According to my mother the rules didn’t apply to females.

The time at Temple consisted primarily of old Jewish men hocking up phlegm.

The holiday was especially tedious due to the hours of holy time spent raising money for the new Temple. Beth Shalom was about to break ground on a modern Holy Shrine to replace our old, narrow, non-air-conditioned place.

As if the annual dues, tickets for High Holiday services, and the Synagogue’s tax free status weren’t enough, and after the Rabbi’s endless financial plea disguised as a sermon, every member of Beth Shalom was called out to contribute money for the new building.

The financially challenged would yell “same,” meaning they were pledging a similar amount as last year. The big spenders would proudly boom “plus ten” which meant they were giving ten percent more than the previous Yom Kipper. I tensed up when the Rabbi got to Nat Schacter, who, alphabetically was a couple of names before Nathan J. “Sonny” Sonnenfeld. Schacter would phlegmishly clear his throat before calling out, for all the congregation to admire, “Plus ten!”

Dad always found a trail to the bathroom a few names before Schacter, and I would sit, crouched low in the hard back breaking pew, hearing, “Nathan J. Sonnenfeld!”

Silence.

“Nathan J. Sonnenfeld?

Silence.

“Marvin Spitzer?”

“Plus ten.”

The last day I attended Hebrew school was a windy, bitterly cold afternoon. Rabbi Baulmal walked into his dungeon-like classroom smoking a cigar, his left arm bandaged from his elbow to his hand.

The Rabbi lived in Riverdale, about a fifteen-minute drive up the West Side Highway from Washington Heights.

Two things happened the day before our lesson, both of which conspired to send the Rabbi’s left arm up in flames.

A toll booth had been installed on the Riverdale side of the Henry Hudson Bridge. It cost a dime. On the very same day, the Rabbi bought a new Buick; his first car with a seat belt.

The Rabbi stopped his Riviera at the new toll gate and, realizing he needed a dime, reached underneath his seat belt into his left pants pocket, whereupon he felt both some change, and a pocketful of strike anywhere matches for his White Owls.

As he struggled to get a dime out of his pants, his hand stuck underneath his confusing and never before worn seatbelt, Baulmal became very conscious of the trail of cars honking behind him. The panicked Rabbi made the soon to be hospital-visitation-inducing mistake of rubbing some of the strike anywheres together inside the dark, claustrophobic pocket of his slacks.

I can imagine the fascinated look on the toll taker’s face, as he watched the Rabbi’s left side start to smolder and finally flame up, the religious leader’s hand trapped in his trousers. I must say, it was so hilariously gruesome, that it almost made me believe there was a God.

A couple of weeks before my bar mitzvah, the Rabbi realized he was about to be embarrassed that I didn’t know a word of my haftorah.

He called my parents.

Busted.

Dad took me from Kenny’s apartment right to Beth Shalom. The class was over and the basement room stunk of Baulmal’s stale White Owls. As we peered through striations of smoke and stench, I heard Baulmal say,

“What are we going to do with you, young man?”

“You mean about me not being able to read Hebrew and my being bar mitzvah’d in two weeks?”

“Precisely.”

“I guess I shouldn’t get bar mitzvah’d?”

“Barry,” said my father, “we’ve already invited people and paid a caterer. You’ll be getting gifts and besides, your mother expects you to be bar mitzvah’d. That’s not an option.”

The evening of my bar mitzvah I would discover the real reason my father wanted me to go through with the charade.

“Well, why don’t I bring in my 3M Wollensak reel-to-reel tape recorder, the Rabbi can read my Haftorah into it, and I’ll memorize it.”

Which is what I did.

Here’s where the event went a little south. Beth Shalom, by this point, was almost finished with their new building. They would be celebrating the first Sabbath in their fancy air-conditioned temple on Saturday April 9. However, they had already sold their old building to an orthodox sect, which was moving in Saturday the 2nd, and they didn’t want us there.

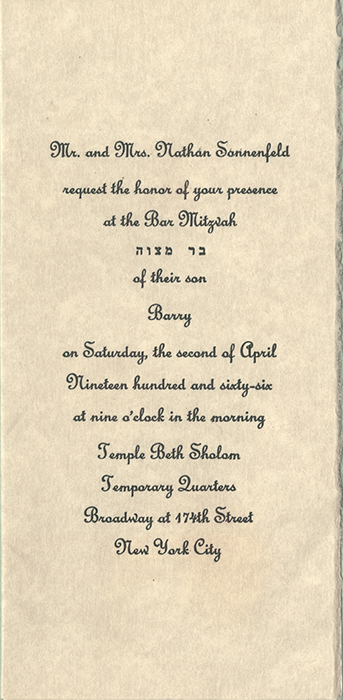

The solution, and I know this sounds too good to be true, was that I was Bar Mitzvah’d across the street from my apartment building in Beth Shalom’s “Temporary Quarters” — which was a Catholic Church. The Rabbi and Cantor entered the Church the night of April Fools — yes, my birthday — and placed large burlap bags over the endless displays of crosses and crucifixes that looked down on the congregation.

Various people are given the honor of being called up to the podium to read passages from the Torah at a Bar Mitzvah. Usually the family picks uncles or fathers, or special friends. They check with the lucky participants ahead of time.

My parents went a different way.

“And now we would like Joe Rabinowitz to come up and read the next portion of the Torah.”

“No,” called out a surprised Joe, who lived in apartment 6C and was the father of Amy, who had been in class with me from kindergarten through, as it would turn out, high school.

“Joe Rabinowitz. Please come up to the front of this uh…”

The Rabbi hesitated to find the right word, as he glanced around the burlap wrapped crucifixes.

“…room.”

“No,” said Joe.

“You can’t say no,” bellowed the blustering Baulmal.

“No. Thank you,” said Joe.

“That doesn’t work either. You are required, when you are called, to come up and read this passage. It’s an honor.”

“Not for me it isn’t.”

My mother walked back to Joe. They had a whispered conversation, during which Kelly was informed that Joe didn’t read Hebrew.

The Rabbi seeing this was going nowhere, left the podium and walked up to Joe. After a heated discussion, and a promise that Joe could read the words in English, Joe caved but was — with good reason — pissed.

After pretending to read/sing my portion of the Torah, which was totally by rote, I then gave my bar mitzvah speech to the assembled guests, which was, and this is April 1966, a plea to end the war in Vietnam. It was ghost written by my mother. I can’t imagine anyone thought the words were mine.

Although the new and improved Temple Beth Shalom’s main floor wasn’t ready for my Bar Mitzvah ceremony, the basement was finished enough for my big, cheap party as long as we didn’t mind the spackle tape and kraft paper covering the floor. The event was in the evening, hours after my Catholic Church appearance. It was an eight block walk from my apartment to the new temple, but mom’s legs were “bothering her,” so Sonny drove.

Kelly insisted I sit on her lap.

When we arrived at the shul, I jumped off mom’s lap as quickly as possible, since really, if a bar mitzvah represents a Jewish boy becoming a man, riding to his manly party on his mother’s lap was just wrong.

I opened the Pontiac’s door, forgot mom hadn’t gotten out yet and slammed the door on her leg.

She should have walked.

For the entire party, my mother sat with her leg up on a chair, bags of ice taped around her ankle and calf. She was as much in heaven playing the role of injured martyr as I was in hell, playing the role of bar mitzvah boy.

My suit was shiny blue with a hint of green, as if lit by a mercury vapor lamp. The jacket had two inside breast pockets, and as the evening went on, they started to bulge as more and more envelopes with E bonds or twenty-five-dollar checks filled them. My pecs were starting to look Schwarzenegger-esque.

When we arrived home, Sonny and I sat on my bed, counting the loot. Over thirteen hundred bucks. A nice stash for a camera and an enlarger.

I would never see that money again. Dad took it, telling me we’d open a bank account the following Saturday. Unfortunately, he “lost” the manila envelope he had put the money in for safe keeping. Coincidentally, we could once again shop at Lou the butcher, and we no longer owed several month’s back rent.

Oedipus, Schmoedipus. As long as you love your mother.

Barry Sonnenfeld is a filmmaker and writer who broke into the film industry as the cinematographer on the Coen Brothers’ first three films: Blood Simple, Raising Arizona, and Miller’s Crossing. He also was the director of photography on Throw Mamma from the Train, Big, When Harry Met Sally, and Misery. Sonnenfeld made his directorial debut with The Addams Family in 1991, and has gone on to direct a number of films including Addams Family Values, Get Shorty, and the first three Men in Blacks. His television credits include Pushing Daisies, for which he won an Emmy, and most recently Netflix’s A Series of Unfortunate Events.