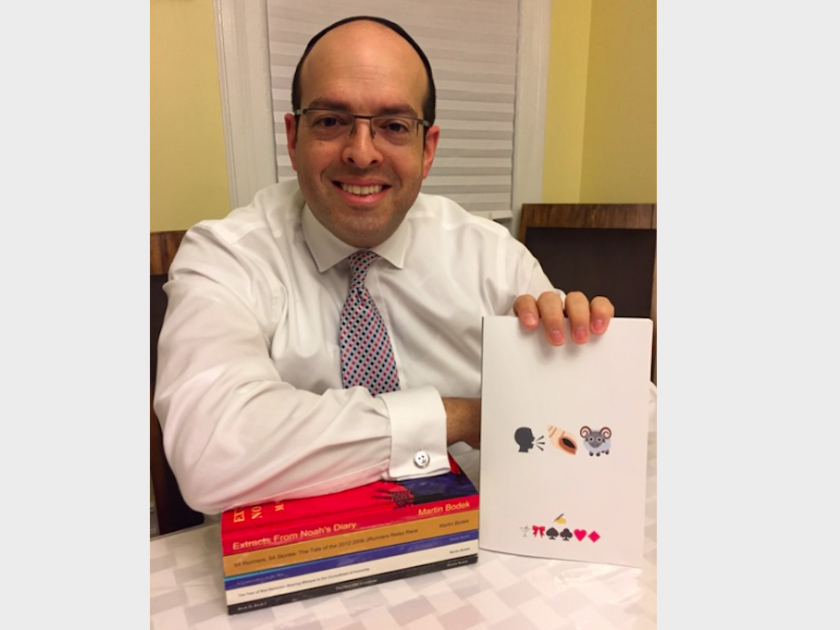

The trials of the bloody, insect-ridden, watery exodus from Egypt have been told and retold in languages across the globe, yet Martin Bodek has found a new way to tell them: with emojis. His beautifully produced haggadah, written entirely with emojis, is a pictorial translation of the English version. I interviewed Bodek over email to get a glimpse of the method behind the meshuggaas.

Ada Brunstein: An all-emoji haggadah — how did this idea spring to mind? Did it come to you in a dream? Was it whispered through the ancestral grapevine?

Martin Bodek: It did not come from dreams within.

It did not come from grapey skin.

It did not spring into my mind.

No, this is how the tale unwinds:

My family always dresses up for Purim, and thus far, as the kids are still young, we’re themed. Our shalach manot follow along with the theme as well, and I always create a little ditty to include in them.

Two years ago, we dressed up as emojis, and we put in all manner of smiley-face stuff in the shalach manot. When it came time to devise the usual poem, I got a little stuck. However, what I settled on doing was drafting the Book of Esther into an emoji synopsis.

When I stepped back from my creation, the first thought that came to mind was, “Hmmm, how could I flesh this out on a large scale?” The full Esther is not what came to mind. Rather, the haggadah flashed instantly, and I got immediately to work.

AB: How long did it take you and what made you persevere through the whole thing (as opposed to, say, doing the four questions and leaving it at that)?

MB: Firstly, Martin Bodek finishes what he starts. There is no, “Well at least you showed up” in my personal philosophy. You’ve got to see things through to the end. This one of the values I try to instill in my children. I won’t even quit board games before they’re officially over.

Secondly, I knew I was brewing something interesting, so that kept me going.

Thirdly, I had self-published five books prior to finding a publisher with this one. I had to keep persevering because I had a feeling that could be my big break. And if not? Then the energy poured into it would be lesson-learning for me. Go big or go home. I choose to go big — or at least, to go all the way.

AB: What were the most challenging sections and why?

MB: The most challenging sections were those filled with conjunctions and prepositions. Words like “but,” “or,” “nor,” and “the” are completely missing from the emoji set, and when certain sections were heavy with them, I felt I might lose some meaning. In the “How To Read” guide at the end of the book, I do my best to explain this difficulty, and hopefully make it easier to relay to the reader how this is properly to be read.

AB: What was your process for searching for fitting emojis?

MB: Originally, with the self-published version, I’d put sefaria.org’s haggadah up on screen, and another tab with iemoji.com. I’d then insert the next word up, pop it into the emoji site, and see what comes up, or whatever is close, or use another word that might stand in. For example, the word “first.” I’d type in “one,” see what comes up. Then I’d type in “1” see what comes up. Then I’d try “first.” Ooh, gold medal. That’s the one, and that’s probably the simplest of all. It got much more complicated than that.

Now, for the published version, you must first understand a pivotal moment in the creation of the book. Here’s a very long story, very short:

I submitted the final manuscript to the publisher. The publisher went to print. The publisher said it didn’t render properly. I would have to use a completely different emoji set, and I had ten days to deadline. I was overseas at the time. I returned, spent a day working out how I was going to interact with the new emoji set, the plug-ins, and drivers, and whatnot. I then rewrote the entire book in six days, after the original took me two years. I did not sleep. After a thirteen-hour typing day, I was done, just in time to watch the end of the Super Bowl, which was tied 0 – 0 at the time, so I missed nothing.

Now with that, I did the same thing: inserted a phrase, saw what came up, found another creative way of phrasing if that didn’t work, and so on.

AB: What were the linguistic parameters you used? Do the emojis represent Hebrew or English text? Do they represent words or sounds or phrases?

MB: I used a large toolset, but I also first started with the simplest translation. The translation itself is directly from the English. My first choice was always to find an emoji that was a direct translation. If I couldn’t find that, I went with an emoji combo. If I couldn’t find that, I’d try a pun. I did not allow myself to get stuck. I had to come up with something for everything. Human names were the hardest. Place names were the easiest — the emoji set is filled with flags.

AB: Can you give an example of a word or phrase you struggled with, along with the different emoji candidates you grappled with before deciding on the final one?

MB: An example comes to mind easily: “field.” There is no field emoji. What was I going to use for field? I went with the emoji for “field hockey,” and prayed that people would get it.

When I started working on the published 2.0 version, this emoji wasn’t there (as a matter of fact, the new set I was working with was fully 1,500 emojis short of the original Apple set I worked with). I went with the emoji for a baseball stadium. That’s known as a field! Perfect — but wait! The plug-in was buggy, and wouldn’t insert it. So I finally went with the emoji that looks like a meadow, my tertiary option. Similar things happened a lot, but that one stands out.

AB: What’s your favorite emoji that you used in the haggadah?

MB: For some strange reason, my favorite was Rabbi Gamliel. Why? Because all other names were mostly literal translations of the name. For example, Yaakov means “heel,” so I put in the shoe emoji. Eliezer means “help of God,” so I put in the SOS emoji, and my symbol for God. Easy.

But what does Gamliel even mean?

I went with a rebus! The game (console) emoji, the Mali flag, and an elf. Smoosh it all together and you have Game+Mali+Elf. Said quickly, it sounds mostly right. I just amused myself to death with that one.

AB: Writing an all-emoji haggadah is pretty out-of-the-box thinking. Have you thought about what other ways there might be of telling this particular story?

MB: I’ll leave that to everyone else I’m trying to leap over in the Amazon rankings. There is an abundance of original haggadahs, several of which I purchased this year, and there’s no end to the creativity on display. I’m just glad I have my part in it all.

AB: You work in technology. Are there ways in which you can imagine tech changing the way we interact with ritualistic texts? (Imagine a guy just like you, fifty years from now. What kind of haggadah is he writing?)

MB: He’s writing an abbreviated version of it, because we are increasingly moving towards getting our information in the shortest form, and in the quickest conduit possible. We have entire websites dedicated to showing you moving clips that are a maximum of seven seconds long. We have a cute movement to define everything in our lives in exactly six words. Whatever it will be, it will be shorter.

The above commentary was highly influenced by a book I’m currently reading called Amusing Ourselves to Death by Neil Postman. It is the wisest book ever written. He is the first son.

AB: What’s your next project?

MB: I’m wondering myself. Once the mania in my life dies down from all the love and attention my book is getting, I’m going to focus on making this decision. The Book of Esther? Do I revisit that? Song of Songs? Metaphor version? Non-metaphor version? Genesis? The Bible? I think I’ll conduct a Facebook poll and see what comes out.

On the non-emoji front, I am currently penning and translating my grandfathers’ memoirs. Both led extraordinary lives, which are worth telling.

Now that I have a relationship with Ktav publishing house, many doors have opened for me. I’ll put myself out into the wind, and see in which direction it will send me.

Ada Brunstein is the Head of Reference at a university press.