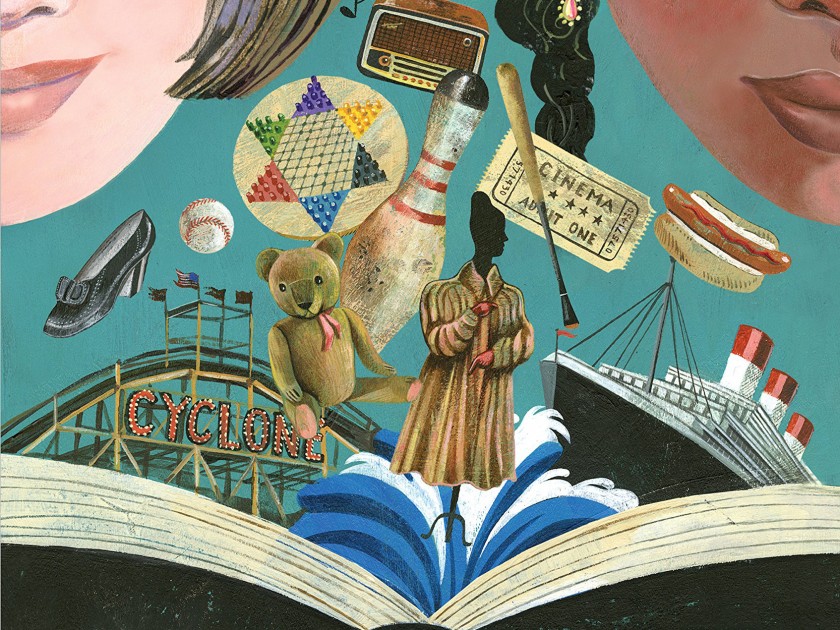

Image from the book cover of The Length of a String

Almost sixty years to the day after a bomb ripped through Atlanta’s most prominent Reform congregation — the subject of my new young adult novel, In the Neighborhood of True—I found myself watching the coverage of the 2018 Pittsburgh temple shooting on an endless cable loop and thinking about Jewish novels that would offer hope and courage to my daughters.

As the culture of hate, fear, and mistrust of “the other” has increased, YA literature has stepped up to counteract it. Antisemitism is rampant — up sixty percent last year alone, according to the Anti-Defamation League — and at this precarious point, broad Jewish representation in YA lit feels more urgent than ever. In the last few years, writers have adopted a bold, diverse view of the Jewish experience with books grappling with racism, LGBT identity, interfaith families, and narrators who turn toward faith or turn their back on it.

Many credit the work of renowned educator Rudine Sims Bishop for leading the charge for increased diverse stories in YA and children’s lit. Bishop wrote about the need for windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors in literature so that underrepresented readers could view their world, see themselves reflected in it, and walk through new openings. Shining light on voices we haven’t heard before has brought a wide range of stories to thoughtful readers in complicated times.

Here are a few of the Jewish authors and novels who are opening windows and doors — as well as hearts and minds.

A Room Away from the Wolves by Nova Ren Suma

Haunting, heartbreaking, and wholly original, this Gothic-esque novel introduces us to the complicated Bina. Early on, Bina’s mother tells her daughter what to do if she’s asked if she’s Jewish: “We should not be afraid and hide what we were. We should look them in the eye and say yes.” But hiding — and lying — are baked deep into Bina’s life. After her mother marries a churchgoer with evil daughters, and asks Bina to move out and crash with church friends for a while, Bina hitchhikes to New York to find Catherine House, a home for girls that once provided refuge for her mom. There, as Bina is attracted to the most mercurial girl in residence, the mysteries escalate until the past threatens to swallow the present. Like the religion she wonders about, Bina is left with more questions than answers. And that ending — wow.

The Length of a String by Elissa Brent Weissman

Imani’s parents promise she can choose her own gift for her upcoming bat mitzvah, but she’s scared to ask for the one thing she really wants: to know her birth parents, whom she calls her blood-and-guts family. Imani, a black girl growing up in a white Jewish family in Baltimore, says the odds that she’s genetically Jewish are probably, like, zero, and she pages through a Children of the World book to guess where she might be from (maybe Ghana, she thinks). Her coming-of-age story intertwines with a different kind of journey — that of her great-great grandmother Anna who ventured from Luxembourg to Brooklyn in 1941 before finding an adoptive family of her own. The twin storylines play off one another in a beautiful, heartfelt way — Imani is devastated to learn that much of Anna’s “first family” died in the camps, and as she learns about one history, she begins to reconsider her own. As Imani says when researching Anna’s Holocaust close call, this was “stuff I’d seen six million times before. Only now, it was like I was looking at them for the very first time.” Exactly.

Lucky Broken Girl by Ruth Behar

We meet Ruthie in 1966, just after she’s been given her first pair of go-go boots, in this exuberant story. Ruthie and her family are newly arrived Jews from Castro’s Cuba and they move into a Queens apartment building with Indian, Belgian, Mexican, and Moroccan neighbors. But the family’s dreams are deferred when, out for a just-because Sunday drive, they’re hit by a car full of drunk boys. Ruthie ends up in a full-body cast for nearly an entire year. Stuck in bed — “my bed is my island; my bed is my prison; my bed is my home” — her inner world grows as she taps into a love of art and searches for forgiveness for the driver who has caused her such pain. While the family’s not particularly religious, Ruthie writes to God, to Shiva, and to Frida Kahlo, the guardian saint of wounded artists. “Some people don’t think you should pray to more than one god,” she says, “but I wonder how many people who say that have spent a year of their life in a body cast.” Authenticity radiates from the page — and it’s not a surprise to learn the novel was inspired by the author’s own childhood.

The Things a Brother Knows by Dana Reinhart

Levi, the main character, introduces himself as a guy with a weird last name who has to call his father Abba like they all still live in Israel. As the novel opens, Levi is anxiously awaiting the return of his older brother, Boaz — a marine who turned his back on college acceptances to Berkeley, Tufts, and Columbia to serve three years in the Middle East. But once Boaz is home, he holes up in his room, not sleeping, tuning the radio to static, and surrounding himself with maps. Boaz tells his family he’s planning a hike on the Appalachian Trail, but Levi has studied those maps and knows better — his brother is heading to Washington, DC … but why? And why on foot? Levi follows his brother; at first he is an unwelcome tagalong, but step by step, mile by mile, the brothers start to open up to one another. Boaz walks, he says, because he still has legs. This is a beautiful book about war and trauma, family and faith — and finding your way back home.

You Asked for Perfect by Laura Silverman

Just in time for the craziness of the college admissions cycle comes this good-natured novel about grade-obsessed Ariel. He’s interested in being first violin and valedictorian, interested in guys and girls, and really interested in getting accepted early to Harvard. He’s so tightly wound, he uses flashcards to memorize his own biography. But under the workaholic façade is a vulnerability that make you root like crazy for him to find more in life. After failing an AP Calc quiz, things start heating up with Amir, a classmate who steps in as an emergency tutor. Ariel’s Jewish faith — family Shabbat dinners, regular Saturday morning services, and a well-timed talk with a wise rabbi — help realign his priorities. The book ends with the author’s great-grandmother’s recipe for matzo ball soup — a pinch of this and a bissel of that — to help nurture us all.

Susan Kaplan Carlton currently teaches writing at Boston University. The author of Love & Haight and Lobsterland, her writing has also appeared in Self, Elle, Mademoiselle, and Seventeen. She lived for a time with her family in Atlanta where her daughters learned the finer points of etiquette from a little pink book and the power of social justice from their synagogue.