“Jews don’t listen — they wait.” Joseph Epstein’s joke about Jews’ eagerness to talk will resonate with anyone who has spent time studying Jewish texts. Many people like to talk back to their books; they make notes in margins or highlight lines for future reference. But Jewish commentary does not merely talk back to books. It screams, sighs, argues, jokes, jibes, and rolls out endless expansions and criticisms. A book is not a dormant object in Judaism — it is a goad and a target. Unlike the marginal notes we make in our everyday books, Jewish commentary is not lost when a book is sold or given away. Instead, the comments become part of the text.

Consider the story of Moses Isserles. A Polish scholar of the sixteenth century, Isserles planned to write a definitive legal work. In the meantime, however, he discovered that the great Talmudist Joseph Caro had beaten him to the punch with the publication of his own legal code, the Shulchan Aruch. Isserles could not hope to write a competing work. He easily might have abandoned his project, but instead he took note of the instances in which Caro, a Sephardic Jew, had recorded practices that were different from his own Ashkenazic customs. In time, no one printed Caro’s code without Isserles’s glosses — the comments were incorporated into the book.

Objections are an essential part of the commentary process; it is not sweet harmony. When the greatest Jewish scholar, Maimonides, wrote his monumental code of law, a formidable sage of the time known as the RABaD (Rabbi Abraham ben David) so disapproved of Maimonides’s attitudes and conclusions that he wrote his hassagot—technically “glosses,” although in fact many are sharply worded rebukes and corrections. In our age, in which it is often difficult to know what is meant by a “Jewish book,” a slightly tautological definition presents itself: a Jewish book is a book that comments on other Jewish books.

Jewish tradition rejects the concept of solo scriptura (“by Scripture alone”). The Bible is a book of silences and spaces. It tells us not to do melachah on the Sabbath, but doesn’t say what melachah means. It tells us that Abraham and Isaac traveled three days together toward the mountain where Abraham was supposed to sacrifice his son, but doesn’t report anything about what they discussed along the way. The rabbis rush into these lacunae with comments, questions, and stories. The study of Talmud becomes a dialogue down the corridors of time.

Jewish learning is not about creating something new, but rather about finding something new. A unique interpretation of a story, an innovative twist on a law — this is the kind of originality that characterizes the Jewish scholarly quest.

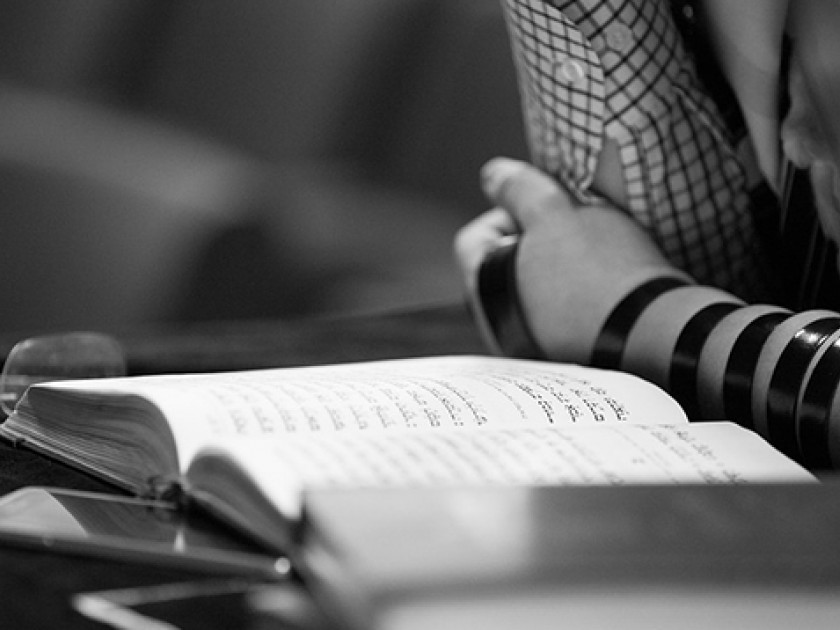

Recently I sat behind a man on a plane who had a Talmud app opened on his computer. On the screen flashed the Aramaic text, the commentary, the English translation, and a note about the English translation. He was essentially reading four texts simultaneously, but all of them were comments on a fifth text (the Mishnah), which was only present as a fragment embedded in the other four. The split-screen communicative chaos of the modern world is not precisely parallel to Jewish textuality. And yet, from early days, Jews have recognized the power of layers of text. Our technological age feels familiar to the student of biblical literature. The Talmud, after all, is an historical hyperlink.

And so each generation absorbs and adds to a vast ascending web of words, seeking to capture the ineffable, vitalize tradition, and reach toward God.

David Wolpe is the Max Webb Senior Rabbi of Sinai Temple and the author, most recently, of David: The Divided Heart (Yale University Press).