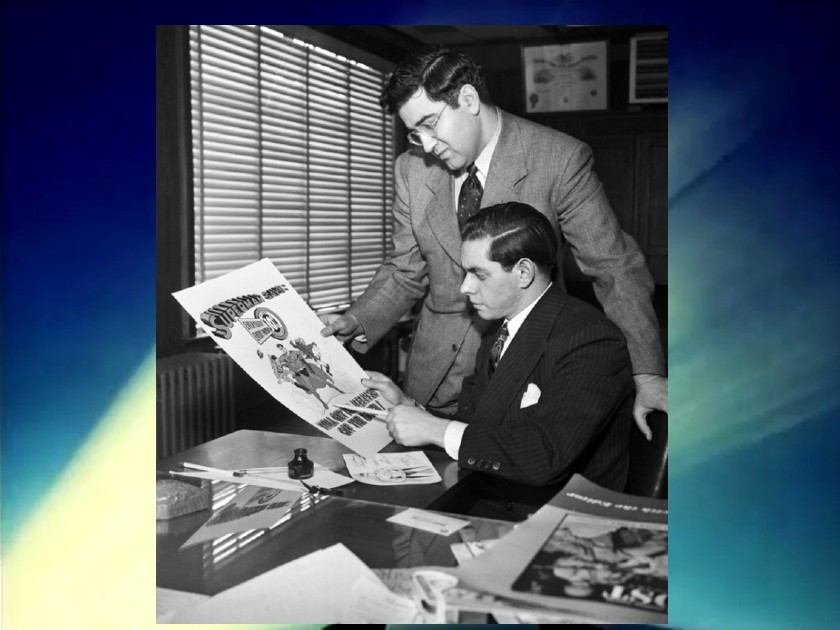

Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, creators of Superman, 1942

Superhero comics are fundamentally Jewish literature. In the 1930s and 1940s Jewish immigrants in New York were kept out of most respectable industries, so publishers, writers and artists created an industry of their own, comics. They also created its proprietary genre, superheroes, which they infused with various levels of Jewish signification.

Less known is that the comic book itself is a Jewish invention. In 1933 an unemployed schoolteacher from the Bronx named Maxwell Gaines (né Ginsburg) came up with the idea of licensing old newspaper strips and reprinting them in a magazine format. (It’s why they’re called “comics,” they were originally all humor strips.) Gradually new content was needed, and five years later, in June 1938, Superman debuted.

The Man of Steel was the first superhero, and the mold from which all others will forever be cast. He’s also a heavily Jewish character. Not canonically but metatextually, as a metaphor and as an avatar of his Jewish creators, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster.

He was given the birth name Kal-El, El meaning god in Hebrew, and the same origin story as Moses; a baby whisked to safety in a small vessel, found amidst thick vegetation, renamed and raised by people not his own, who grows to become a great savior. In several versions he travels across the North Pole and learns of his special heritage from the hologram of his father Jor-El, mirroring Moses’s journey across Midian and the burning bush.

Siegel acknowledged being inspired by Samson, the super-strong Israelite judge who fought in the name of truth and justice, whom he regularly references in the early comics. He was also inspired by the golem of Prague — particularly the 1920 film — in creating an indestructible champion of the oppressed. (In 1958 the golem legend was used wholesale for the origin of Bizarro, one of Superman’s most famous adversaries.)

Siegel and Shuster based Superman’s alter-ego, Clark Kent, on themselves. They were both bespectacled, gawky and neurotic, but also cerebral, inventive and wisecracking — a checklist of Jewish stereotypes.

Superman is essentially the story of the Jewish refugee Kal-El who came over from the old country and anglicized his name to Clark Kent. He’s an alien who can pass for human but can only interact freely with society through a disguise, a Jew passing for a non-Jew. His costume is made from the Kryptonian fabrics his mother wrapped him in as a baby, and he wears it under his clothes like a tallit, giving him the ability to change identities at whim.

Other superheroes from the period reflect their Jewish creators’ background and preoccupations as well. Captain America, for example, created in 1941 by Joe (Hymie) Simon and Jack Kirby (Kurtzberg), is about a young weakling of strong resolve who volunteers to become a super-soldier to fight the Nazis, equipped with a star-spangled shield. It echoes the story of King David, a genteel youth of unwavering faith who volunteers to fight the giant enemy of his people, later fashioning a hexagram shield, the Star of David.

What makes comics Jewish isn’t just the history of their creation; it’s the rich tapestry of Jewish themes and symbolism that can be found within them.

Captain America’s alter ego is Steve Rogers, an undersized young artist from the Lower East Side, just like his co-creator Jack Kirby. Kirby plainly stated that “Captain America was me, and I was Captain America.” When the Captain punched Hitler on the cover of his first issue — dated March 1941 and published December 1940, a year before Pearl Harbor and when the vast majority of Americans were staunchly against intervention — it was Kirby’s “own anger coming to the surface.” And when the press was relegating reports about the ongoing Holocaust to the back pages, the cover of Captain America Comics #46 showed tagged inmates marched at gunpoint to giant ovens, human bones sticking out of the ashes.

The image in most people’s minds of 1950s comics is cheerful and carefree, but in truth many became post-Holocaust allegories, an outlet for their Jewish creators.

The most popular genre was horror, not superheroes, and Superman became increasingly haunted by the destruction of his home world and extinction of his people. Story after story, he struggled with survivor’s guilt, discovered other Kryptonian survivors like his cousin Supergirl, and tried to learn about and preserve his lost culture.

In the 1960s, Marvel Comics revolutionized the industry with new forms of storytelling and an explosion of new characters, many co-created by the Jewish duo Stan Lee (Stanley Lieber) and Jack Kirby.

These new creations continued to reflect Jewish themes, like the X‑Men, a persecuted minority of mutants who can largely pass for human, sworn to protect a world that hates them, who learn how to use the gifts of their special heritage in a yeshiva-like private school. The series explored, and still does, questions of identity, integration vs. tribalism, and coexistence.

Comics’ worst-kept secret is that Spider-Man, the most profitable superhero, is Jewish. A neurotic nebbish from Forest Hills, Queens, a heavily Jewish neighborhood then and now, he quipped constantly with ironic, self-deprecating humor sprinkled with Yiddishisms like oy.

Later on, writer Brian Michael Bendis — a former orthodox yeshiva student who wrote the character longer than anyone else — added mishugas, fakakta, shmendrick and references to holidays like Shavuot. In the 2018 animated movie Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse Peter Parker can be seen, for a split-second, stepping on the glass at his wedding.

In the 1970s Kirby wrote and drew a multiyear, multi-series saga called the “Fourth World” about warring alien gods, where the good guys were based on Jewish archetypes and the bad guys on Nazi archetypes. Almost every issue was brimming with biblical, Talmudic, and Kabbalistic allusions.

Jewish creators increasingly brought their background to the foreground in other genres as well, producing works like Trina Robbins’ 1972 Wimmen’s Comix, Harvey Pekar’s 1976 American Splendor, and Will Eisner’s 1978 A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories. Art Spiegelman’s Maus received the 1992 Pulitzer Prize.

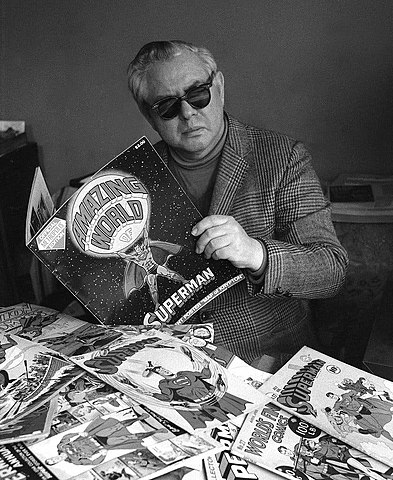

Comics’ Jewish parentage has been increasingly acknowledged in recent years. In 2002 Will Eisner received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Foundation for Jewish Culture, in “recognition that in many ways the [comic book] genre is a Jewish-created genre.” In 2000 Siegel and Shuster were named in The Jewish 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Jews of all Time, and in November 2021 they were inducted into the Jewish-American Hall of Fame.

But what makes comics Jewish isn’t just the history of their creation; it’s the rich tapestry of Jewish themes and symbolism that can be found within them.

These themes, while presented metaphorically and hyperbolically, are the same as those of twentieth century Jewish-American literature. Siegel, Shuster, Simon, Kirby, Lee, and other early comic book creators came from the same background and wrote and drew about the same things as Roth, Bellow, Wouk, Malamud, and Miller. They deserve to be on the same shelf.

Superman co-creator, Joe Shuster, in a press photo by DC Comics, 1975

Roy Schwartz writes about pop culture for The Forward and CNN.com. His work has appeared in New York Daily News, Philosophy Now, and IGN, among others. He has taught at CUNY and is a former writer-in-residence fellow at the New York Public Library. His latest book is the Diagram Prize-winning Is Superman Circumcised? The Complete Jewish History of the World’s Greatest Hero.