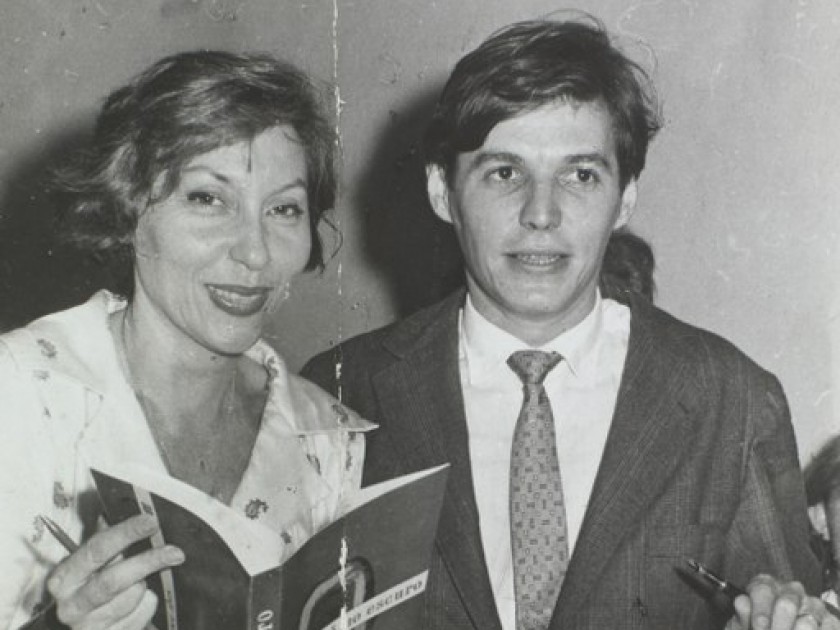

Clarice Lispector e Tom Jobim, sem data. Fundo documental: Correio da Manhã

Benjamin Moser, author of Why This World: A Biography of Clarice Lispector, is guest-blogging for MyJewishLearning and the Jewish Book Council.

At many points in my life, I have been glad to know Yiddish. But as I darted through the darkened lobby of the Hotel National in Chişinău at one in the morning, trying desperately to reach the elevator bank before I was spied by a man with a stained beard and rancid breath, I reflected that this was not one of those points.

I had come to Chişinău, the capital of Moldova, once more widely known as Kishinev, to follow the path that took the family of the great writer and mystic Clarice Lispector, then an infant called Chaya, from their Ukrainian homeland to Brazil.

Despite the bad roads and the chaotic border crossing, it was a short trip from Chechelnik, the tiny town where she was born, to Kishinev. Although, it would not have been a short trip in the early 1920’s, when the Lispector family was trying desperately to flee the pogroms, famine, and civil war that, in the wake of World War I and the Russian Revolution, were ravaging their homeland.

The numbers will never be known, but hundreds of thousands of Jews were killed in those years, the worst episode of anti-Semitic violence in centuries. The events that followed World War I were the Holocaust’s opening act, though they are today almost completely forgotten, even by Ukrainians and Jews, for whom even worse was shortly to come.

The victims included Clarice’s beloved mother Mania, who was raped by a gang of Russian soldiers in 1919 and contracted an untreatable venereal disease that would kill her when Clarice was nine. Yet the Lispectors were luckier than many: Mania’s husband and daughters survived, and she herself lived long enough to see her family safely established abroad.

Clarice Lispector, the tiny infant her heroic parents carried through this wasteland of rape, necrophagy, and racial warfare, grew up to become Brazil’s greatest modern writer, a legendary beauty once called “that rare woman who looked like Marlene Dietrich and wrote like Virginia Woolf.”

Yet despite her passionate attachment to Brazil, I suspected, when I started doing research into her unbelievably dramatic life, that her Jewish background, and what happened to her family during those terrible years in Ukraine, was in many ways the key to that life.

One afternoon in Rio de Janeiro, Clarice’s elderly cousin entrusted me with a precious document: the Yiddish memoir her father, Clarice’s uncle, had written about his own escape and immigration. I had to read it: one of the only known eyewitness accounts of those events. And so I sat, relying on my knowledge of German, my extremely rustic Hebrew, and an old Yiddish dictionary, going through that precious document one word at a time. As I went along, I grew more confident, and by the time I finished it I could read Yiddish more or less comfortably.

But while I loved reading it, I’d never had a chance to speak it until the fateful day I reached Chişinău. The city, while pleasant, is not overburdened with tourist attractions, and so it wasn’t long before I wandered onto Habad Liubovici Street, where the city’s only remaining synagogue operates. Out front, as bored, underemployed, and friendly as everyone else in Moldova, a few Jewish men were standing. One asked me, in Russian, if I spoke Yiddish, and my visible excitement was my first big mistake. I was so delighted to be yabbering away in Yiddish that I let myself be adopted by the merry band, even putting on tefillin and posing, hand on the Torah, for a particularly horrible picture.

I revealed that I was staying at the Hotel National (second mistake) and then, my fatal final mistake, disclosed that, following the route of the Lispector family, I would be travelling to Bucharest the next morning. An older man perked up, and volunteered his nephew, a truck driver, to escort me. This gentleman clearly had a drinking problem, and I immediately realized that quick action would be required to escape his invitation. I made up an excuse, headed back to the hotel, walked around, went to dinner (Chişinău has surprisingly good restaurants), and returned to the immense Soviet pile of the Hotel National.

As it happens, the hotel had already prepared me for the experience of being spied upon. Each floor had a female attendant planted in the hallway to clean the rooms, change the sheets, and, more to the point, serve as a bribeable, beturbanned Rosa Klebb, keeping a glazed eye on the goings-on inside.

In Europe’s poorest country, these jobs were not to be despised. Even in the National, once a showplace, the dreadful economic situation was never far from one’s mind: after a certain hour, the lights were dimmed to save electricity, and I returned to a Hotel National bathed in evening gloom.

To my alarm, my Yiddish-speaking friend from that afternoon was sitting in the giant lobby, lying in wait, between the doorway and the elevator. I was sure that the money I could pay his nephew would be important to him, and I did not want to feel like one of those Parisian or Viennese grandees of yesteryear, peering down through his lorgnettes at the unwashed Ostjuden. On the other hand, Ireally did not want to sit for twelve hours in a Moldovan truck with a possibly alcoholic stranger, and so I decided to make a run for it, whooshing up the stairs to the first floor, boarding the elevator, and all but collapsing into the arms of my astonished hall monitor.

“I am not here,” I said to her emphatically, slipping her a few leis.

She nodded gravely.

The next morning, with her help, I went out a side entrance, got in a cab, and reached the train station.

Benjamin Moser was born in Houston. He is the author of Why This World: A Biography of Clarice Lispector, a finalist for the National Book Critics’ Circle Award and a New York Times Notable Book. For his work bringing Clarice Lispector to international prominence, he received Brazil’s first State Prize for Cultural Diplomacy. He has published translations from French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Dutch. A former books columnist for Harper’s Magazine and The New York Times Book Review, he has also written for The New Yorker, Conde Nast Traveler, and The New York Review of Books.