Minna Zallman Proctor is the author of Landslide: True Stories, out September 15th from Catapult. She will be blogging here all week for Jewish Book Council’s Visiting Scribe series.

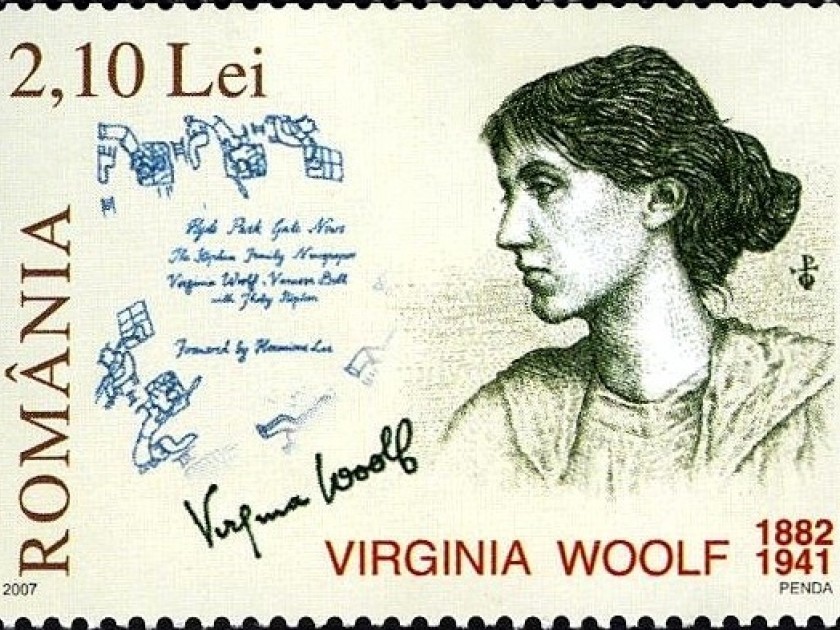

Writing the occasional piece, such as this one, is a special kind of torture. Not least because I’ve had in mind for as long as I can remember putting names to forms that the term “occasional piece” actually and officially described something literary (and not a piece of furniture). And that “something” would correlate to a blog post — a gorgeous lineage that would have taken its primordial urge in vast antiquity, philosophy and spiritual writing, taken form under Montaigne and rolled forward steadily gathering variations on substance and style through Virginia Woolf, to the contemporary moment. Though if the writing has been a shapely snowball descending through the centuries, its labels have been troublesome entropic pebbles. I have decided to call this an “occasional piece” for the same decorative reasons that I decided my book of personal essays should be referred to not as personal essays but as true stories and although there were moments in the course of writing them that I was convinced I was advancing theories of narrative forms, I was more accurately writing memoir. Oh, for the days when everything long was a novel and everything short a story.

There are three most important tools for an essayist, or memoirist: truth, storytelling, and observation. Though classified historically as automatic writing or stream-of-consciousness, seldom as memoir, Virginia Woolf’s occasional pieces are paragons of intricate and sensitive observation, in which the evolution of her perception is always the story itself, and truth breathes like an organism in her perfect transparency.

Virginia Woolf tossed them off — my fantastical perception. I have this (potentially ahistorical) idea that in the period before blog posts, the occasional piece was an exercise, a writing calisthenic that Woolf performed muscularly between novels. She was exercising her pencil — why a pencil? Because it was the pursuit of a pencil that led her out walking “half across London,” late afternoon, in “Street Haunting.” “No one perhaps has ever felt passionately towards a lead pencil. But there are circumstances in which it can become supremely desirable to possess one.” Though widely anthologized, however, I can’t read “Street Haunting” with pleasure. To me it reads too much like work, like sweaty, impeccably executed calisthenics and a treatise on observation: “The eye is sportive and generous; it creates; it adorns; it enhances.”

Her pencil led her in brilliant circles. Frequently cited as Woolf’s first published “short story,” “The Mark on the Wall,” is more than story or essay in any classical sense a dramatic musing. I have a colleague who lectures eloquently about “The Mark of the Wall,” singing out in his lectures the brutal devastation of the First World War — the voluminous compression of a war story seen in a spot. As devastating the final shrinking of all life, all those young boys’ lives lost, to a mark on the wall, I can’t read that magnificent piece as anything but an indictment of domesticity. This pencil at work, flying over the pages, almost orgiastically as it searches for what, or rather where, the mind will lead, I hold my breath every time because I know what’s coming — they always do in real life. There’s “a vast upheaval of matter and someone is standing over me — .” Her husband has walked into the room, the scene, onto the page. The spell is broken as it always is when a writer is absorbed back into life. The piece must end because that was the time allotted by circumstances to the thought, the journey, the door on the room of her own, after which there must be resolve. It is only a piece and inspired yet formed entirely, as blog posts must also be, by its occasional-ness.

My heart instead belongs entirely to “The Death of the Moth.” For in this very small piece a battle is waged for significance, vastness, and eternity by a very small moth — “He was little or nothing but life” — and the moth wins. Because in the course of this most remarkable account, Woolf transforms the moth: “Watching him,” she writes, “it seemed as if a fibre, very thin but pure, of the enormous energy of the world had been thrust into his frail and diminutive body.” Here Woolf ignites a cosmology, a spiritual transcendence, the link between her ability to see, witness, observe and what’s vast and unseeable, what makes faith.

With her pencil, Woolf prods at the moth in her window frame, as if by righting its tiny body, she could suspend its death throes. “I lifted the pencil again,” she writes “useless though I knew it to be.” But a moth, coming to the end of its life cycle, doesn’t need saving from death — the gesture is useless — it needs, we need, its life to be saved from insignificance. Which she does, ultimately, by lifting her pencil and putting it to paper — a moth, a testament, the book — immortalizing the moment, this moment, and linking it to eternity.

Can one hope that in all these words, this proliferation of words that fills every screen and waking moment, there are some few, exquisite ones that can stop time long enough to see God?

Minna Zallman Proctor is a writer, critic, and translator who currently teaches creative writing at Fairleigh Dickinson University, where she is also editor in chief of The Literary Review. Her most recent book is Landslide: True Stories. She is also the author of Do You Hear What I Hear? An Unreligious Writer Investigates Religious Calling and has translated eight books from Italian, including Fleur Jaeggy’s These Possible Lives. She lives in Brooklyn.