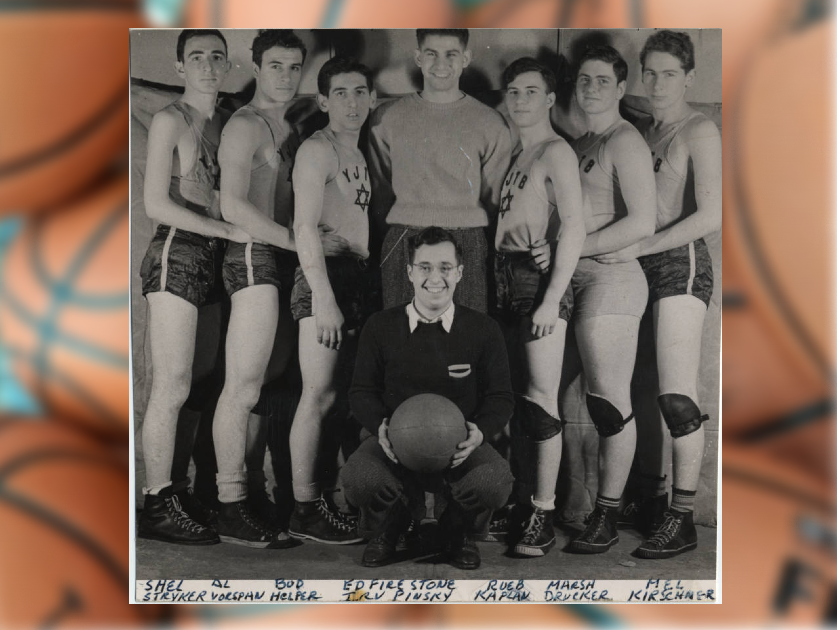

Young Judea Trailblazers basketball team, 1940, Jewish Historical Society of the Upper Midwest

From the Steinfeldt Photography Collection of the http://www.jhsum.org

They first made an exception for my brother Andy. He was the first Jewish kid allowed to play for our local CYO team — he was that good. Then, a new rule allowed the team to accept three non-Catholic players per year. That’s why I was able to join three years later.

Basketball has always been about belonging. That’s what James Naismith intended.

In 1891, when Naismith invented basketball, he was thinking about immigration. He was an immigrant himself, new to an America that was experiencing its as yet largest influx of immigrants. Sure, Naismith was from Canada, so he looked and sounded much like the majority white Anglo Americans who feared and resented the many immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe and China. Outsider and insider: perhaps being both at once placed him in a unique position.

All the while, Naismith had problems to solve. On a micro-level, he needed to come up with an engaging game that phys-ed students could play in a confined, indoor space during the winter. But on a larger level, he was, in devising this new game, serving the greater Young Men’s Christian Association’s mission to elevate the mind, body, and spirit of the urban American laborer. He was thinking of all the people living and working in small, cramped spaces, in tenement apartments and overcrowded factories. And while the YMCA spread the game to its Christian membership from city to city, it did not welcome, and often excluded, millions of immigrant newcomers — primarily, Eastern European Jews and Southern European Catholics. Fortunately, basketball itself was accessible, and these groups found it an ideal way to demonstrate their assimilation. For the next half-century, then, the game became the animating force for new and first-generation urban Americans to Americanize — to prove that they belonged. In a country where the burning issue was how to “deal” with immigrants, Naismith’s solution worked like nothing else.

Basketball has always been about belonging.

Jews, in fact, pioneered organized basketball in the United States. Hundreds of thousands fled persecution in Eastern Europe, making their way to cities like Boston, Cleveland, Seattle, Chicago, and Philadelphia. By 1920, half the Jews living in the US were in New York City. But even here, they were met with crude institutional antisemitism. The New York City police commissioner declared that half the city’s criminals were Jews. Harvard president Charles Eliot chimed in and stated that Jews were overly intellectual, crafty, physically inferior, and should not be permitted to intermarry. And barred from accessing field sports due to cost and discrimination, the Jewish community built parallel indoor athletic facilities at community centers, such as the Young Men’s Hebrew Associations and settlement houses. Chief among these facilities was the University Settlement House, which created a “basketball faculty” led by Harry Braun. Braun’s innovation elevated the sport entirely. Borrowing from lacrosse, he created the fundamentals of up-tempo play: quick short passes, moving without the ball, keeping your head up, and always looking for an open teammate. His figure-eight style of constant movement came to be called “Jew Ball,” which served as the basis for successful motion offenses of NBA champions like the Knicks in the seventies, the Lakers in the eighties, the Bulls in the nineties, the Spurs in the 2000s, and the Warriors in the 2010s. The settlement-house basketball teams had become some of the best in New York City. University Settlement won the Inter-Settlement League championship in 1903, 1904, and 1905; in 1907, it swept the Senior and Junior Division championship titles in both the Inter-Settlement League and the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU). The earliest professional leagues were dominated by Jews, including Hall of Famers Dolph Schayes, Barney Sedran, Harry Brill, and Nat Holman.

Similarly, Catholics coming from Ireland, Italy, Poland, and Croatia were labeled as criminals, anarchists, and socialists who would ruin the United States. Demagogic politicians said that the way to stamp out their Catholicism was to put them through the public school system. To preserve their religion and culture, the Catholic community created a separate education system. As poor as the communities they served, but eager to prove they belonged, these schools needed a sport that required little equipment and no grass. They landed on basketball. It was through this system that an innovative first-year coach— Ray Meyer at DePaul University in Chicago in 1942 — pegged a gawky, bespectacled six-foot-ten George Mikan as the future of the game, training the big man to move like a little man, which revolutionized the game. Mikan ushered in the birth of the NBA, and Catholic school basketball became an American treasure, with its high schools and colleges serving as perennial twentieth- and twenty-first century powerhouses.

As the Notorious B.I.G. observed of dire urban conditions, “the streets is a short stop / either you’re slingin, crack rock or you got a wicked jump shot.” Options were similarly limited for urban ethnic minorities in the early twentieth century. The earliest teams fronted ethnic labels. There were Jewish teams from Michigan like House of David and Chinese teams from San Francisco like Hong Wah Kues. The New York Celtics were made up of Irish, Dutch, and German immigrants. And although they were still legally and socially segregated, Black Americans had formed successful teams known as the Black Fives, like the Harlem Rens. These teams appealed to in-group fans but also gave the marginalized newcomers public platforms for pride and cultural assimilation. Forty years into his invention, and through two generations of the United States’s most robust and socially fractious period of immigration, Naismith’s basketball had become a means of redefining who was American — and a powerful tool for national cohesion.

Last year, my NYU class joined the people of a small mountain village in Italy, and, on Good Friday of 2022, we helped convince the Pope to recognize the first-ever Patron Saint of Basketball — the first patron saint of any team sport. I guess it took a Jew to make a Saint.

Naismith once wrote: “I seek to serve god … wherever that may be.” What he created was an accessible space where all of us, if only temporarily, could feel the joy of belonging and community. Amen to that.

Read David Hollander’s How Basketball Can Save the World: 13 Guiding Principles for Reimagining What’s Possible.

David Hollander, JD, is an assistant dean and clinical professor with the Tisch Institute for Global Sport at New York University and received NYU’s highest faculty honor, the Distinguished Teaching Award. He sits on the advisory boards for espnW, the Earl Monroe New Renaissance Basketball School, and the NYU Entrepreneurial Institute. He holds his high school’s record for most technical fouls in a season and a career.