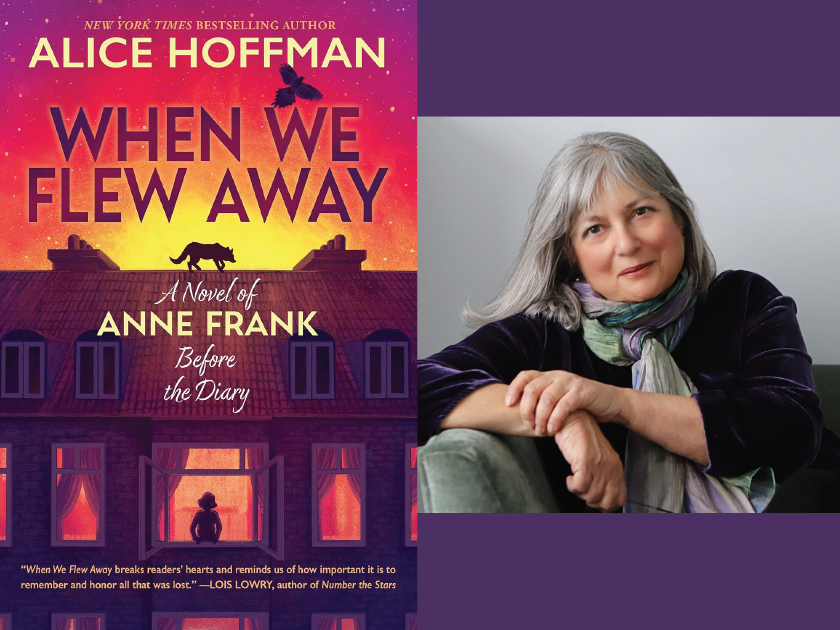

Author photo by Alyssa Peek

Acclaimed author Alice Hoffman has written over thirty works of fiction for readers of all ages. Now, in her middle-grade novel When We Flew Away: A Novel of Anne Frank Before the Diary, she brings her immense talent to reimagining the life of Anne Frank in those precious years before the family went into hiding.

The lyrical, fairy-tale-esque prose in When We Flew Away immerses us in Anne’s dreams for the future, her relationship with her older sister, and her desire to be understood. This coming-of-age story is perhaps more powerful because the reader knows the tragic ending that looms, and yet still feels the hope and courage that propel Anne and her family as the Nazi regime tightens its hold on Amsterdam between 1940 and 1942.

Simona Zaretsky: I want to start off by asking about the experience of taking such an important and iconic story and fictionalizing it. I know The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank was also hugely influential to you as a young reader. What was the research process like?

Alice Hoffman: Scholastic approached me with the idea — which has never happened to me before — and before I could even think about what it would mean in terms of research, or the difficulty of imagining Anne’s story, I said yes, right away. I felt it was meant to be, like a full-circle moment; Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl was one of the reasons I became a writer. This project came to me toward the end of my career. I felt like it was the book that my grandmother would want me to write more than any other book. So, I didn’t even think about the challenges. I didn’t think — I just said yes.

The Straus family archives were very helpful to me, as was Joan Adler at the Straus Historical Society. I rent a little cottage to work in and, strangely enough, it turns out that it’s owned by a member of the Straus family. It was through him that I was able to gain access to the archives at the Straus Historical Society. I wrote a big part of the book in this little cottage he owns. The odds of that happening just seemed super slim.

SZ: Oh, that’s wonderful. The story is framed by haunting fairytale-style paragraphs under the heading “What We Lost,” and then parts one through five, which focus on Margot and Anne. Could you speak about the framing of the larger stories through these fairy tales? I was also curious about the role that justice and fairness play, because I think fairy tales often have their own rules.

AH: That’s actually a great question, because I had a lot of difficulty when I started thinking about how I should tell this story. I didn’t want to reread the diary because I was imagining a piece of Anne’s life from before it, so I didn’t want to have in mind what happened after my story was told. The things that happen are so horrific and unbelievable that I thought the only way to tell this story would be as if it were a fairy tale, or a myth. To me, that’s the purpose of fairy tales: to tell you about all the terrible things that are out there and all the ways you can have the courage to face them. As a kid reading fairy tales, I felt that they had a deep psychological truth that’s lacking in other children’s books. They depict cruelty, but also hope.

SZ: In that vein, I was struck by the black moths that creep in Anne’s periphery, multiplying and tapping away. I thought that really paralleled the restriction of rights and humanity that’s happening in Anne’s world during this time. And it’s only Anne who can see them at first.

AH: It’s funny, because when you’re writing fiction, you don’t think about symbolism. It kind of arises as you’re writing. I went on a trip and there were huge black moths, one of which lingered outside my door. What is this black moth doing? I wondered. When I asked the people there, they said that the black moth is often a messenger of death. I was like, Oh, great. I thought it was so interesting for such a beautiful creature to be symbolic of death or evil. So it just kind of showed up in the story when I started writing.

SZ: Similarly, Anne is devoted to and fascinated by magpies. Could you talk a bit about the natural world in an urban setting?

AH: I live in an urban place, and during COVID, we started to see turkeys, foxes, and coyotes. It’s like they were reclaiming the city now that people weren’t going out as much. Even though people were doing horrible things; the natural world was still what it was.

SZ: The sense of foreboding throughout the story is so strong. As readers, of course, we know the tragic ending. But I still sensed there was hope. How did you manage to weave positivity into a story about such tragic world events?

AH: That was a hard thing to do. I think I had to take after Anne and the voice in her writing, which is more positive and hopeful than my own. And I think a great lesson for all of us.

SZ: How did you tap into Anne’s voice?

AH: When I said yes, I knew I couldn’t write the book in the first person, because Anne has already written the best first-person narration in literature. And very often when I write for young people or just in general, I like to write in the first person because you get inside their perspective. So I had to figure out how to get inside her head but not speak for her. I was afraid; I wanted to do her justice.

SZ: I want to ask you about the relationship between Anne and Margot. They’re in the position to understand each other more than anyone else, and yet they find themselves at odds with each other. This quote felt so indicative of their relationship: “They were so very different, but they were sisters all the same. You can love someone who doesn’t understand you. That’s what Anne had decided. You can trust them more than anyone else.” Could you speak a bit about how you developed their relationship on the page?

AH: I write very often about sisters. I don’t have a sister, so that’s a huge emptiness in my life. A lot of how I depicted Anne and Margot came from research. Margot, it turns out, really was the beautiful one, the well-behaved one — the favorite in a lot of ways. Within families, there’s often this feeling that you take on a certain role.

Anne had to find her own role, one different from her sister’s. And she was difficult, according to the few people I met who knew her. (Of the two sisters, I relate more to Anne!) Despite their differences, at the end of their lives they were together constantly. They took care of each other and — I feel like crying — they died within days of each other. I based most of their relationship on this piece of research that I had read about the end of their lives and, in a sense, I wrote their relationship backwards from this time. It really shaped my thinking.

To me, that’s the purpose of fairy tales: to tell you about all the terrible things that are out there and all the ways you can have the courage to face them.

SZ: Anne’s parents play interesting roles in the book. Anne feels understood and valued by her father. But in her mother’s eyes, she can do nothing right. How did you craft those important relationships?

AH: My research revealed that Anne and her father had a special relationship, and that he kind of favored her. She had a fraught and complex relationship with her mother, and her parents’ marriage wasn’t a love match. I used those details and imagined the rest.

SZ: In the book, the Franks’ house (their home before going into hiding) is a kind of character, safe and warm.

AH: When I went to the house, I was actually invited to stay there, which I couldn’t do. Today, the house is open to writers who aren’t able to write in their home countries. The house is in a beautiful neighborhood. It feels very safe. I think it was a great neighborhood when the Franks moved there. There were a lot of immigrants coming in then. And the house itself is lovely. Even being there for a short visit was super emotional for me.

SZ: Oma, Anne’s grandmother, understands Anne in a way that no one else does. Oma escaped the Nazi regime in Germany and then, once again, found herself in the wrong place at the wrong time, in Amsterdam.

AH: It’s like they picked the wrong place to move to, but of course you just never know how things are going to work out. I based a lot of that grandmother – granddaughter dynamic on my own relationship with my grandmother, who was Russian and the person that I was closest to growing up. I’ve always believed that if you have one person in your life who supports you completely, then you’re really fortunate. And I think that was true of Anne. I know it was certainly true for me. So I was writing about my grandmother in a way.

SZ: The final moments in the book are a powerful call to document and act as a witness, even if you don’t have the chance to see what comes of that preservation. Could you speak a bit about this?

AH: When we read about the Holocaust, we know how it ends. But people at the time didn’t see it coming, and they didn’t want to. Up until the end, they couldn’t believe what was happening to them. (Although Otto Frank — and others who went into hiding — were preparing.)

SZ: This is a coming-of-age story for Anne and Margot. Anne comes to see what her parents have been shielding her from, but she pretends not to in order to alleviate their worry. Throughout the story, Anne has an unquenchable thirst to be older, which eventually becomes tempered. Could you talk about her somber coming of age?

AH: The first time I ever went to the Anne Frank House, I saw photos of somewhat modern movie stars. When you read The Diary, you imagine that its events took place so long ago. But they didn’t. This was all happening during relatively recent times. I knew the names of the movie stars. Anne’s dreams— wanting to go to California and be a writer — are such typical girlhood dreams. She was special, but she was also ordinary. That made me feel closer to her and her story.

SZ: What was the writing process like for When We Flew Away?

AH: The writing process for this novel had many stages. The initial research and notetaking one, and then outlining, drafting, and more research followed by my visit to Amsterdam. Then I did more revisions and worked with my editors. It always seems to me that when you finish the book you forget these different steps because the project is whole and it has become what it’s meant to be.

SZ: What are some of the books that shaped you when you were the age that Anne is in When We Flew Away?

AH: Anne Frank’s diary was really important to me. Ray Bradbury, too. Reading Bradbury when you’re twelve or thirteen can change your life. His novel about book burning and banning, Fahrenheit 451, had a huge influence on me because I spent so much time in the library. When I was younger than that, I read books by Edward Eager, which I just loved. He had a whole series of magic books, including Half Magic. And I used to steal books from my mother’s bookshelf, so whatever she was reading, I was reading.

SZ: What are you working on now?

AH: I’m working on a couple of things. One is a book about women in the 1950s and the seventeenth century, looking at the similarities in the way they were treated. It wasn’t so long ago that women weren’t allowed to wear pants. There were, and still are, so many things off-limits to girls. So I’ve been thinking about the things that women haven’t been allowed to do throughout history.

When We Flew Away: A Novel of Anne Frank Before the Diary by Alice Hoffman

Simona is the Jewish Book Council’s manager of digital content strategy. She graduated from Sarah Lawrence College with a concentration in English and History and studied abroad in India and England. Prior to the JBC she worked at Oxford University Press. Her writing has been featured in Lilith, The Normal School, Digging through the Fat, and other publications. She holds an MFA in fiction from The New School.