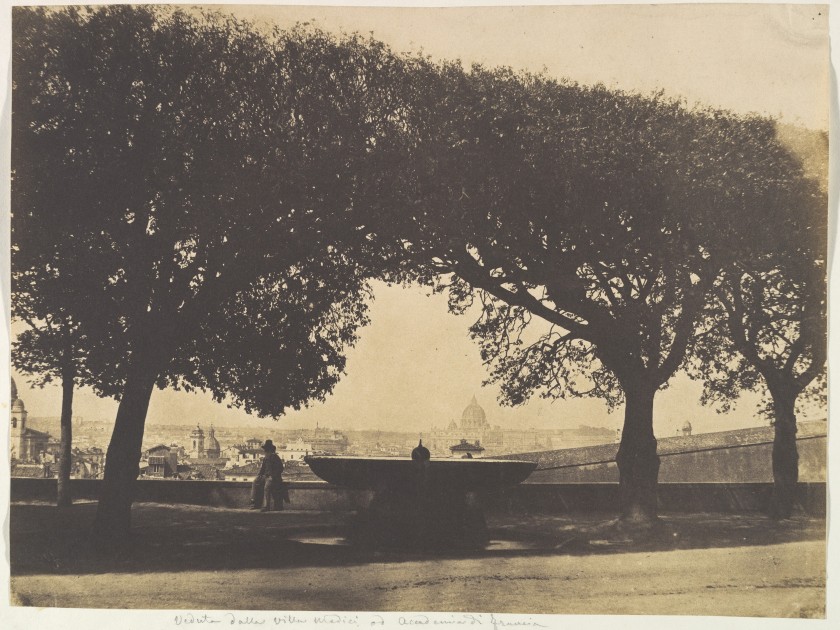

View from the French Academy at the Villa Medici, Giacomo Caneva, Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005

Call Me By Your Name, André Aciman’s portrayal of a first, greatest, and (possibly) only love, was published to much acclaim in 2007. The novel tells the story of the relationship between Elio, a seventeen-year-old fluent in Mozart and Paul Celan, and Oliver, the slightly older classics scholar staying with Elio’s family at their home in northern Italy. Call Me By Your Name is both a steamy page-turner and a lush meditation on memory and youth. Peaches, Herodotus, and puking on the street have never seemed more romantic.

Now, twelve years and one Oscar-winning film adaptation later, Aciman has written a sequel — well, as he notes, maybe not a sequel, but a new novel inspired by the earlier book. Find Me picks up thematically where Aciman left off, but differs from its predecessor in both form and sweep. This novel is comprised of four parts, each a different story of love or lust featuring a character from the earlier book. The chase in these romances is not as prolonged; lovers recognize one another almost instantly and make bold pronouncements and impulsive commitments. Despite this immediacy, Aciman’s interest in our tendency to wonder what might have been propels these stories, which are filled with poignant discursions about regret, recollection, and desire.

Russell Janzen: What prompted you to return to Elio and Oliver’s love story after twelve years?

André Aciman: I wrote Call Me By Your Name very hastily, and basically felt that it was unfinished. I tried writing a sequel many times, and either it didn’t work or there were other things that got in the way, and so I finally just threw my hands up in the air — until I realized that I liked this story of Elio and Oliver. I trusted it, and I wanted to go back to it. And about three years ago, I started fiddling around with a sequel again, and eventually it took off.

RJ: Have you ever returned to characters before?

AA: No, never. I do end up writing in one particular voice, or about one particular personality — which is usually similar to my own, but I throw it into all kinds of situations. That particular identity, let’s call it, floats all over the place. So I go back to it, and I think I always will until I stop writing. But this was a unique case in which I wanted to return to three specific characters from an earlier book.

RJ: What was it like to return to the characters after seeing them brought to life by actors in the film?

AA: For a while after seeing the movie, I couldn’t remember who my characters were because they had been superimposed by Timothée Chalamet and Armie Hammer. So it was very difficult for me to visualize them. But in this instance, with the passage of time, I saw different people. First of all, Elio and Oliver are much older, and also I was no longer under the spell of the film.

RJ: And it really did cast a spell.

AA: Well, it did on me, too, to be honest. I mean, I thought it was going to be just another movie made from a novel, but it was actually quite moving. Even for somebody who knew the story already!

RJ: Initially, I kept making comparisons between Call Me By Your Name and Find Me, but then I wondered if that was fair. So before we go ahead: how are the two books connected? Is Find Me an extension of Call Me By Your Name? A follow-up? Something more separate than that?

AA: Well, it’s inspired by Call Me By Your Name. It’s not really a follow-up, though yes, it picks up the characters years later, and they have matured and changed. If they have a lasting bond, sometimes they lose track of this bond because they don’t always communicate — but something keeps hovering in the back of their minds. At some point they realize that it’s never going to go away, and that they want to go back to it if they can. So in that respect you can say that that portion of the book — which is a very slim portion — is a continuation of Call Me By Your Name. Otherwise, Find Me is about the same characters, who are essentially caught drifting through life but have a point of anchorage that they will seek out again.

If they have a lasting bond, sometimes they lose track of this bond because they don’t always communicate — but something keeps hovering in the back of their minds.

RJ: It was such a beautiful choice to start with Samuel, Elio’s father, and Miranda, this new love in his life. In revisiting these characters, what drew you to begin with Samuel and Miranda meeting?

AA: Samuel’s the easiest character for me to identify with. After all, he’s around my age. I understood what his compulsion was, and how he had basically given up on the greatest thing of life — a great love — and now here he is, entering into a relationship that he had absolutely no plan for and maybe no hope of ever having again. And he has to decide whether to take it or not.

RJ: Even though there are moving stories of romantic love in Find Me, the through line is Elio and Samuel’s connection. Did you go into writing the novel intending to deepen that?

AA: Yes. It was a very weird thing — sometimes you know where you want to go, but you find yourself distracted by the material in between. I began with a character who was taking a train to meet his son, and who happened to speak to a woman sitting next to him with her dog — and suddenly that woman with the dog became more and more compelling for me the writer, and for Samuel as well. So I kept pushing off the meeting of Elio and Samuel. And eventually it got pushed back to the very end of Samuel’s tale.

But what I wanted to capture — because I think it happens to all of us — is that we start off giving advice to those who are much younger than we are: our children. Eventually, as we mature, guess what? They’re the ones giving us advice. I wanted to turn the tables on Samuel, to give him a son who is extremely grateful for what his father has given him throughout his life, and who is now telling his father something that fathers seldom hear from their sons.

RJ: I know you have three sons. Has your relationship with your sons had a large impact on these stories?

AA: No, not at all. But I have a very open and frank relationship with my sons, as I had with my father, who was an extremely frank and candid man. That part is there in the novel.

RJ: You’ve written a lot about time in both of these novels, and I’ve noticed you do this kind of loop-de-loop where the story moves forward and then it loops back ever so slightly. Could you describe how you thought about time in this book in particular?

AA: I think this is partly a question about time, and partly a question about craft. Time itself always moves forward. But I’m also always interested in memory, and in the particular dimension of time that could be called the conditional mood. It’s not the present tense or even the past or the future tense. It’s the should-have-might-havedimension that we live with- — a might-have-been universe, or fantasy — which underpins our entire life trajectory.

But if you’re speaking of craft: I remember doing this when I was writing Call Me By Your Name, too. You begin to describe a certain act, but you leave some of the details out. And then three, four, five pages later, the character remembers what happened at that earlier moment and provides the reader with further details, details that were omitted from the first telling. And I love this — you called it looping back, which is exactly what it is. A way of continuing a narrative as if what has just been said needs to be told once more. This is also exactly what happens when you meet someone again after five years, ten years, twenty years. You are constantly returning to something you’ve already returned to.

RJ: Right before reading Find Me, I read an essay you wrote about W. G. Sebald titled “The Life Unlived.” In the essay, you connect this idea of the might-have-been to Jewish identity and the Holocaust. Though it’s not a huge part of Call Me By Your Name or Find Me, Jewishness does feel essential to your characters. Is there something about this idea of the might-have-been that ties into their Jewish identity in particular?

AA: Hmm. That’s a good question. For Jews, there is a sense that you are constantly returning to the past, not because you are afraid of the present or because you don’t trust the future — it’s more that the past is always with us. We rehearse the past time and again, and pass the memories on to others, so that not only the beauty of the past is remembered, but also the scars that came with it. It’s not just that we evoke the past, but also that we evoke reevocations of the past — what I call “rememoration.” And you might say that this is a Jewish trait. Or, let’s say, Jews have been the most vocal practitioners of this specific trait.

RJ: In the second section of the book, Elio begins a relationship with an older man, Michel, who shares with him a handwritten piece of music — a cadenza — given to his father by a Jewish pianist during the German occupation of France. Both this discovery and the cadenza itself involve revisiting different points in the past. This ties into the idea of “rememoration,” too, right?

AA: Yes, because the cadenza wasn’t inspired by just one composer or piece of music; it contains many pieces jumbled together, and each one wants to have its say: the Beethoven, the Mozart, the Kol Nidre, and so on, each in a way evoking and rememorating the other. They are each asking to be given their place.

But I think this kind of automatic return to the past is something I do all the time — both in my life, which I don’t like to talk about much, but also, especially, in my writing, where time is a very important factor, because it tells us how close we are to that moment when we’ll have no more time. That’s what the obsession with time is all about. It’s not about youth and adolescence; it’s about how close we are to death.

That’s what the obsession with time is all about. It’s not about youth and adolescence; it’s about how close we are to death.

RJ: I noticed how you use, and don’t use, names in Call Me By Your Name and Find Me. They seem to be revealed — or not — in very intentional ways. Like we never know what Samuel’s childhood nickname is even though he reveals it to Miranda.

AA: No; you never know. He doesn’t tell you.

RJ: At one point in Find Me, Elio says, “I told him my name,” but you don’t actually tell his name to the reader right away. Is there a specific power or intimacy in using someone’s name in a relationship?

AA: I have a particular hesitancy about giving out a character’s name, particularly that of the protagonist. I don’t divulge a name too quickly or openly. It’s a very private thing. It’s part of one’s identity. In Call Me By Your Name, the reader doesn’t find out Elio’s name until quite late in the story. And if you look at Proust, for example, it is only toward the very end of In Search of Lost Time that you find out that the narrator’s name is Marcel. Throughout the whole book, which is probably the most private novel ever written, you don’t even know his name!

You’re giving away a great deal when you give away a name. And when you want somebody to call you by their own name, you’re basically opening all the gates, all the doors, all the windows — everything is open. You are vulnerable.

You have no idea the number of letters I get where people tell me, “We called each other by each other’s names. Wow! It was a very powerful moment.”

RJ: I imagine your novels often make people want to open up to you.

AA: Yes, they do. It’s a pleasure to have that happen because it is exactly what Call Me By Your Name is, in a way, asking people to do: Now that you’ve read me, tell me about you.

Russell Janzen is a New York-based writer and a dancer with the New York City Ballet.