Excerpt from Daniel and Ismail, courtesy of the author.

A few years ago, I was a guest at Chile’s book fair in Santiago where I stumbled upon an unexpected children’s book about fútbol, the world’s most important sport. The book was called Iguales a 1, which could mean “the same as one” as well as “tied 1 – 1.” The author was Juan Pablo Iglesias and the illustrator, Alex Peris.

I was surprised because it is very difficult — in fact, almost impossible — to find children’s books in Latin America (with the possible exception of Argentina and Brazil) with Jewish themes. The reasons are complex. Perhaps there isn’t enough of a market, as a result of antisemitism and other reasons; Jews keep a low profile, not integrating their culture fully into the mainstream. But this book was even more unexpected: it was about two boys, Daniel and Ismail, one Jewish and the other Palestinian, playing soccer in an unnamed city park.

But this book was even more unexpected: it was about two boys, Daniel and Ismail, one Jewish and the other Palestinian, playing soccer in an unnamed city park.

I bought it and read it right away. Soon after, Iglesias, out of the blue, introduced himself to me. We talked about a number of topics, not only Iguales a 1 but, more expansively, the fact that Chile has what is believed to be the largest Palestinian community outside of the Arab world, around 450,000 to 500,000, which is roughly the size of the entire Jewish population in Latin America. By comparison, Chile has around 15,000 Jews. At the end of our encounter, I suggested to Iglesias the possibility of publishing the book in the United States.

As I reread the book during my flight back, it dawned on me that it should not only be made available in English, but that it should appear in a trilingual format: English, Hebrew, and Arabic. The Israeli-Palestinian peace process was then at one of its lowest points. Perhaps Iguales a 1 could inspire some hope.

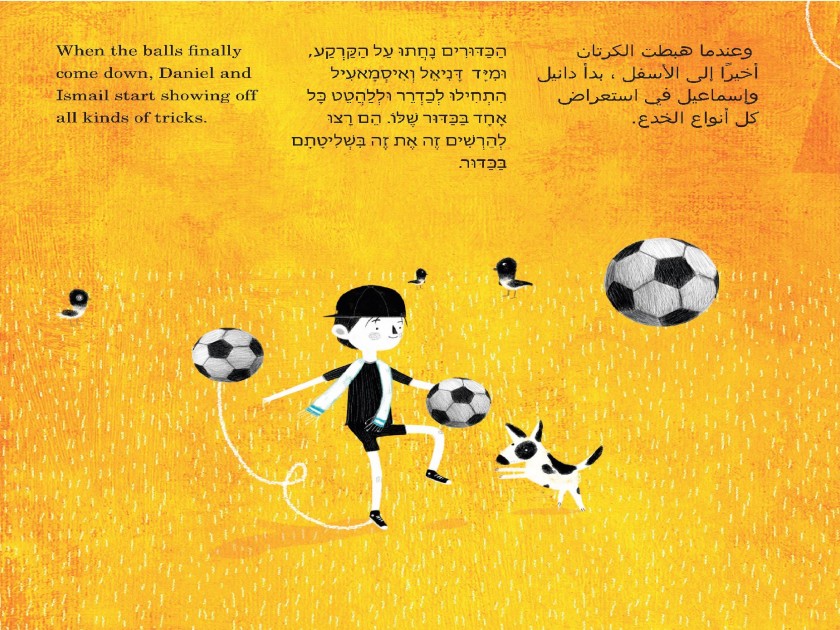

The plot is delightful. Daniel and Ismail, total strangers, happen to have the same birthday. As a present, their parents give them a couple of items. Daniel gets a tallit — a Jewish prayer shawl — and a soccer ball; Ismail gets a keffiyeh — a scarf traditional to Arab countries — and also a soccer ball. Inspired by the latter, the two run to the park to play. They use the tallit and keffiyeh as goal markers. For the next few hours, they just enjoy each other’s company. When it gets dark, they both realize they are late. As they dismantle the goal, they mistakenly take the wrong item: Daniel takes home the keffiyeh and Ismail the tallit.

Excerpt from Daniel and Ismail, courtesy of the author.

Only when their families greet them do they realize their mistake. The parents become angry. It is rare for children’s books in the English language to be explicit about the fear and even hatred of other groups. We believe — foolishly — that we must shelter children from the realities of adulthood. They always get it, though. The boys are told to return the items the following day. This they do, except that instead of simply exchanging the prayer shawl and keffiyeh they again use them as goal markers and start playing again. Soon they are joined by other kids in the park. Together they play a game of fútbol.

We believe — foolishly — that we must shelter children from the realities of adulthood. They always get it, though.

From vision to reality, the publication of Daniel and Ismail in the United States has been an unlikely challenge. Iglesias and Peris were delighted with the idea. Children’s books don’t travel easily from one culture to another. I did the translation into English, in part, because I wanted to lend my name to the project. It required some subtle maneuvering because the symmetry between Daniel and Ismail is only superficial.

Though both the tallit and the keffiyeh are traditional scarves, the former is a religious item and the latter is a cultural signifier. So, Daniel is Jewish, but not necessarily Israeli. Meanwhile, Ismail’s keffiyeh tells us nothing about his religion, or even his nationality. Given that Daniel and Ismail come from Chile, is it fair to imply that Ismail is Palestinian? That, at least, was the assumption I made.

At Restless Books, where I am the publisher, acquiring Daniel and Ismail required much discussion. It was clear the book would pose all sorts of challenges. Who was its audience in the English-speaking world? Hopefully parents and children. Was the plot contrived? Not really. And could the publication be imagined in a different way: not only in English but in Hebrew and Arabic? That strategy would expand its reach. It would also invite readers of all ages to reflect on friendship across ideological divides.

The challenge was set. We embarked on a crowdfunding campaign to raise $12,500 to cover production, given there would be so many unknowns upon publication. We also consulted with children’s book specialists. How should the three languages occupy the pages? How to design them in order for the text not to distract from the illustrations? After all, a good picture book delivers its narrative concurrently via images and text. In the end, we decided that the book should read right to left, like Hebrew and Arabic books, and that all three languages should share each page.

How should the three languages occupy the pages? How to design them in order for the text not to distract from the illustrations?

The ordeal was to find willing translators. There are scores of them but we quickly realized that the Arabic translation involved making choices. Should the language sound like Arabic spoken in Ramallah, Cairo, or Amman? Or should it sound like the Arabic spoken in Santiago, where the language has absorbed a large number of Hispanicisms? Even more complicated, as we made some editorial choices, we discovered that Arabic translators simply didn’t want to have their work appear on the same page with Israeli translators — there would be consequences for their careers at home. The divide was almost insurmountable.

In the end, we found first-rate translators willing to participate. The work of polishing the three versions — in English, Hebrew, and Arabic — to make them compatible took months. And then, we needed to find copy-editors also capable of proofreading all the versions.

The expectations are high for Daniel and Ismail. Will the endeavor be seen as Quixotic, bringing Jews and Arabs, Israelis and Palestinians, together in a joyful story? Should children not even be told about how impossible the dialogue between these two groups has become? Or will fútbol project its magic again, allowing a respite in a conflict that seems without end?

One thing is clear to me: bringing out a book in these troubled times takes effort.

Ilan Stavans is the internationally known, New York Times bestselling Jewish Mexican scholar, cultural critic, essayist, translator, and Amherst College professor whose work, translated into twenty languages, has been adapted into film, theater, TV, radio, and children’s books.