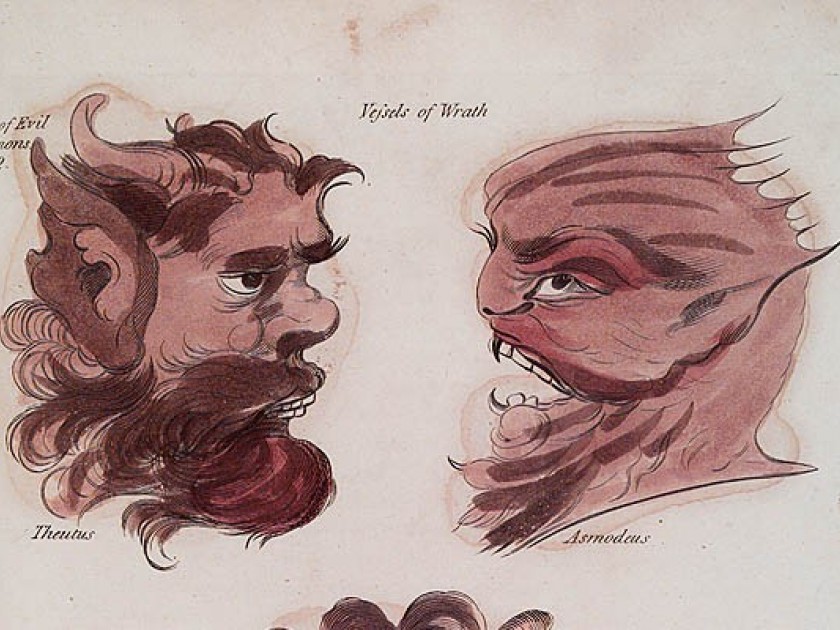

Demons Theutus and Asmodeus, hand-coloured etching from Francis Barrett’s book The Magus,1801

In the 2021 horror movie, Paranormal Activity: Next of Kin, an evil demon named Asmodeus possesses people and inspires murder, mayhem, and various forms of villainy. He also shows up in the TV series Supernatural as the Prince of Hell. In fact, the demon appears frequently in pop culture. And whenever he rears his head, he is usually associated with hell, evil, and general wickedness.

But Asmodeus is not the creation of modern minds. He is actually very old — very, very old.

While Jewish tradition knows this demon as Ashmedai, the Aramaic version of his name, the oldest evidence for Asmodeus comes from the Avesta, a sacred Zoroastrian text that is over two thousand years old (parts of it may be almost a thousand years older than that).[1] In the Avesta, aēšmō.daēva (literally translated as the “Wrath demon”) works to sow violence in the hearts of humankind and spread evil in the world. aēšmō.daēva? Sounds a lot like Ashmedai, no? [2]

This demon next shows up in the Book of Tobit, an apocryphal Jewish text from the third or second century CE that survives in the form of a Greek translation. In the story, a woman named Sarah becomes the object of Asmodeus’s lustful obsession. Though she has been married seven times, she has never consummated any of her marriages; for Asmodeus has killed each of her husbands on their wedding night. The hero, Tobias — guided by the angel Raphael — successfully exorcizes Asmodeus, marries Sarah, and the two live happily ever after. (Asmodeus is similarly malevolent, and opposed to the consummation of marriages, in the Testament of Solomon, a syncretic text with Jewish underpinnings.)

In all these texts, Asmodeus is evil and directs his violence towards human beings. Given how he is presented in modern media, such a depiction should seem familiar.

But here’s where things get weird. Or, at least, weirder.

Because the next place where Asmodeus, now Ashmedai, appears is in the Babylonian Talmud, which depicts him quite differently than older texts. Here, Ashmedai has received a promotion, and now he is King of the Demons. Yet the differences go beyond his title.

The longest extended Talmudic story about Ashmedai is set during the reign of another king, King Solomon. When King Solomon is building the Temple, he needs to find something called a shamir in order to quarry the required stones. Solomon plans to kidnap Ashmedai and force him to disclose its location. The human king asks some other demons where to find the demon-king, and they reply:

He is on such-and-such mountain. [Solomon asked:] How will I recognize it? [They responded:] He has dug a well, and filled it with water [to drink], and covered it with a large flint rock, and sealed it with his seal. Every day he ascends to the heavenly academic session and learns the heavenly Torah lesson, and then descends to the earthly academic session and learns the earthly Torah lesson and inspects his seal and uncovers [the well] and drinks and covers it and leaves. [3]

All of a sudden, Ashmedai is a Torah scholar, who spends his days studying Torah in two yeshivot — one in heaven, one on earth — where he is presumably learning alongside other scholars.

Knowing his schedule and where he snacks every day, Solomon sends his servant to kidnap Ashmedai, binding him with a chain that bears the ineffable name of God. Over the course of the story, Ashmedai demonstrates his expertise by quoting and interpreting biblical verses, offering insights into the world around him, and sharing his wisdom as it relates to King Solomon. He also helps Solomon get the shamir and build the Temple. But for all his help, Solomon keeps Ashmedai bound until, one day, the human king asks his demonic counterpart what makes demons so special. Ashmedai responds: “Take the chain [with the name of God inscribed upon it] off of me and give me your seal-ring [inscribed with the name of God] — I will show you how I am greater.” Solomon does so, and when Ashmedai is freed, he hurls Solomon four hundred miles away and steals his identity, ruling in his place until the rabbis uncover the ruse and banish Ashmedai from the palace.

Here Ashmedai is both a sympathetic character and an eventual usurper of the Davidic throne. Such disjunction has led some scholars to argue that the Talmudic narrative combines different traditions about the demon-king. In any case, it is clear that Ashmedai is not pure evil; he’s a wise demon, a Torah scholar, and a profoundly complex figure. His depiction is part of a larger strategy by the rabbis of the Babylonian Talmud to portray demons as neutral, obedient to God’s will, and part of the rabbinic system. But it also illustrates the danger of letting demons into that system. After all, given their ability to move between heaven and earth, they may end up more knowledgeable about Torah and more wise than the ultimate wise man, King Solomon.

The story of Asmodeus doesn’t end there: medieval Jewish texts depict Ashmedai as even more complicated. One midrash tells a story in which the demon Igrath assaults King David in his sleep, and she conceives Ashmedai as a result. Ashmedai, then, is both the product of rape and a legitimate heir to the Davidic throne — a detail that may hint at an explanation for why he challenges Solomon in the Talmud. Another medieval depiction can be found in the “Tale of the Jerusalemite,” a Jewish fairy tale in which an unnamed young man ends up lost in a province inhabited entirely by demons who pray, attend synagogue regularly, and are ruled by a benevolent and extremely pious king. This king, Ashmedai, tests the young man on his Torah knowledge and then hires him to teach his son. Eventually, the young man marries Ashmedai’s daughter, and they have a child — before the young man’s own misbehavior catches up with him.

From an evil and wrathful Zoroastrian demon, to a lustful Jewish demon, to demon who is a Torah scholar and member of the Davidic dynasty, Asmodeus continues to be an important figure in Jewish folklore, emerging as good, evil, and something in between. And while modern popular culture has fixated on these earlier models of a purely evil Asmodeus, Jewish texts and traditions remind us that the story is always far more complicated — just like Asmodeus himself.

Read Sara Ronis’s Demons in the Details: Demonic Discourse and Rabbinic Culture in Late Antique Babylonia.

[1] https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/avesta-holy-book

[2] https://iranicaonline.org/articles/aesma-wrath

[3] b. Gittin 68a‑b

Sara Ronis is Associate Professor of Theology at St. Mary’s University in San Antonio, Texas.