Mary Antin, My Cuttyhunk Journal, from Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America

Winner of the 2019 Jewish Book of the Year Award, for America’s Jewish Women: A History from Colonial Times to Today, Pamela S. Nadell answers some behind-the-scenes questions on figures in her book and trends of America’s Jewish women, as well as how she’s faring in these turbulent times.

Staff: How are you keeping sane in quarantine?

Pamela S. Nadell: For a writer facing a deadline, quarantine feels familiar. I am doing what I usually do — sitting in my airy study, researching, writing, more researching, rewriting, more rewriting. My guilty pleasures are extra walks with the dog (who is now utterly exhausted) and cooking dinner. Fortunately, I love to cook.

My classes were small enough this semester that we just continued our discussions online in real time. Knowing that my colleagues everywhere were also quarantined, I invited those whose works we were reading to drop into my class. They brought a silver lining to my online classroom.

Staff: Were there women that you did not write about that you would have liked to add to the book but didn’t?

PSN: Sadly, so many notable women with compelling stories ended up getting cut from my manuscript, especially scores of well-known Jewish women, prominent activists in second-wave feminism. But there were others too. In 1881, Nina Morais Cohen responded to an anti-suffragist who, convinced that women’s smaller brains proved their inferiority, argued against their getting the vote. Morais brilliantly dismantled her arguments. Living in an era of rising antisemitism, Morais also defended the Jewish people against its slurs.

Staff: Which woman had the biggest impact on you as a writer?

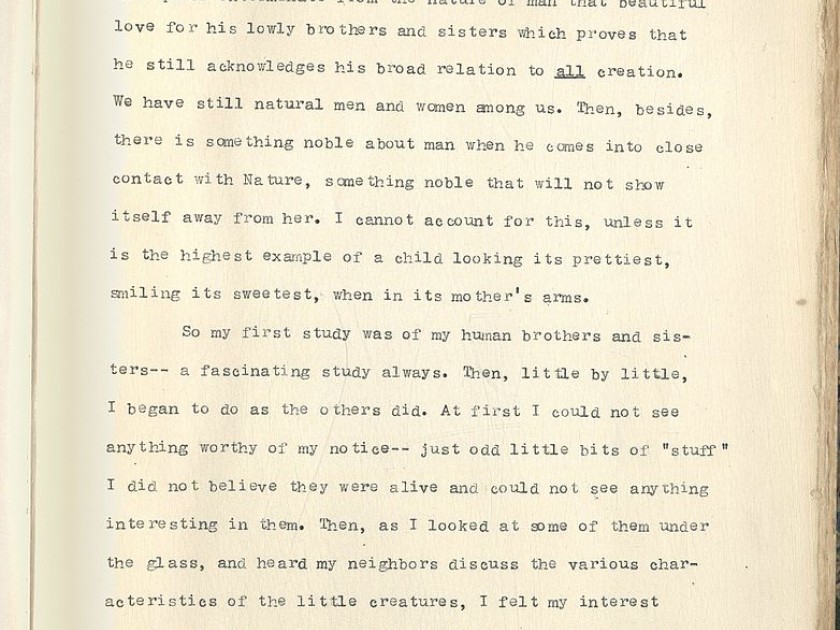

PSN: I can’t name just one! Two stand out — Mary Antin, whose autobiography The Promised Land I read my first year in graduate school, and Kate Simon, whose evocative first memoir Bronx Primitive I read the year I became a professor. To this day their determination to get an education, overcome the roadblocks they faced, and the way they told their stories inspire me.

Staff: What started you on the journey to write this book?

PSN: Since childhood, I was drawn to stories of women’s lives. I pulled so many biographies of famous American women — Betsy Ross, Clara Barton, Amelia Earhart — off the children’s shelves of my New Jersey township’s library that I assumed that famous women had their own juvenile series. They didn’t. I just wasn’t grabbing the books on Washington, Jefferson, and Lincoln. Looking back, I imagine that stack of biographies launching me into women’s history.

Staff: Briefly unpack the word Jewess: negative or positive?

PSN: This question made me laugh. I think there is a generational divide here. I use the word when America’s Jewish women used it. The first English-language Jewish women’s periodical (1895−1899) was called American Jewess. Thanks to Google Ngram, which traces the frequency of words across millions of pages, I know that the use of “Jewess” precipitously declined after 1940. Of course, Ngram doesn’t capture media. It cannot show if there was an uptick after Gilda Radner’s Saturday Night Live “Jewess Jeans” skit or now as podcasters use the word.

Staff: Which Jewish women do you think are blazing the trail today that you would include if you were writing this book in the future?

PSN: No matter how many Jewish women trailblazers I would name, I will be slammed for those I have left out! Just think of the great numbers of Jewish women who have entered national, state, and local politics; or the myriads who are leaving their marks in the worlds of business, the arts, education, the media, and activism. But I would like to pay special tribute to the hundreds of women who have become rabbis, among them the first to receive Orthodox ordination.

Staff: Read a short passage from a book written by one of the women you discuss/cover in your book.

PSN: This is a passage from Kate Simon’s Bronx Primitive (1982). Here Simon writes of a conversation from half a century before she published her first memoir: “My mother didn’t accept her fate as a forever thing… while I was still young, certainly no more than ten, I began to get her lecture on being a woman…’ Go to college. Be a schoolteacher… and don’t get married until you have a profession… Or don’t get married at all, better still.’”

There are so many possibilities in those words.

Staff: Share a few #DidJewKnow(s) about Jewish women in history.

PSN: Rosa Sonneschein, editor of the American Jewess, was one of a handful of American Jews who attended the First Zionist Congress (1897).

Dr. Joyce Brothers launched her TV career, not as a psychologist, but as a boxing expert, winning $128,000 on the TV game show The $64,000 Question.

At the University of Chicago, Heather Booth founded Jane, an abortion referral service. It helped 10,000 women get abortions before Roe v. Wade.

Staff: The book starts in colonial times — is much or anything known about Jewish women who were here before the founding of the country? If so, what are some facts that stand out to you?

PSN: For colonial times we have, of course, fewer sources. But we do have some treasure troves of letters and even poetry.

One collection, buried in the archives, comes from Grace Mendes Seixas Nathan, whose great-granddaughter was the famed poet Emma Lazarus. I love hearing Grace Nathan’s voice in her letters. She grumbles about a neighbor’s “hum-drum wedding” and shares worries about a great-niece who has been spitting up blood for weeks. But the doctors are not terribly concerned; they think that her corsets are too tight.

Staff: How did you decide who to classify as an American Jewish woman?

PSN: Years ago, when I was a member of the editorial board of Jewish Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia, we had heated discussions about who was in and who was out. For this book, my rule of thumb was if someone was either born Jewish or saw herself as Jewish, then she was in.

Staff: Were there historical women you discovered over the course of your research whose lives might challenge our preconceptions? Who was the most unexpected figure you came across?

PSN: If our preconceptions are that in the past America’s Jewish women were primarily wives and mothers, caring for their families and communities, then so many of the women in my book broke that mold.

Maimie Pinzer was a prostitute who preferred that life to sewing in a sweatshop until her aching fingers bled. Annie Nathan Meyer founded Barnard College but opposed women getting the vote. Communist organizer Peggy Dennis sent her daughters to school on the High Holidays but kept them home on May 1st, International Workers Day.

Their lives, I think, do not fit most preconceived notions about America’s Jewish women.

Pamela S. Nadell is the Patrick Clendenen Chair in Women’s and Gender History and director of Jewish studies at American University. Her works include the 2019 NJBA Jewish Book of the Year, America’s Jewish Women. She lives in North Bethesda, Maryland.