Earlier this week, Devorah Baum wrote about five books that counter the “negative” narrative of Jewish literature and the twelve most stereotypical Jews in literature. Today, she explores seven books that capture the breadth of Jewish experience. She is the author of the book Feeling Jewish (a Book for Just About Anyone), out this week from Yale University Press. She has been blogging here all week for Jewish Book Council’s Visiting Scribe series.

Israel Zangwill – Children of the Ghetto: A Study of a Peculiar People

A book of portraits and scenes of late 19th-century Jews in London on the cusp of modernity and modernization. This book by the so-called “Jewish Dickens” was a best-seller, in part because it managed to do two opposing things at once, for distinct audiences: it opened up a closed world, that of the poor immigrant Jews, to non-Jews and assimilated middle-class Jews, thus creating pathways for understanding between groups that appeared “peculiar” to each other, while at the same time opening up vistas to the world beyond the ghetto for the Jews residing within it.

Aharon Appelfeld – For Every Sin

Appelfeld is one of the greatest writers of imaginative fiction relating to the Holocaust. His prose has an uncanny feel to it, which conveys something of the state of loss, displacement and exile that characterizes its author’s own strange position vis a vis language: he had to learn to speak a smattering of different languages in order to survive the war alone as a child in Europe before he arrived in Israel and made of Hebrew something at once entirely modern, or even modernist, and yet in such a way that his writing still retains the depth and significance of its scriptural sources. While this is apparent in all his work, it’s in his novel For Every Sin that the tortuous relationship of the survivor to language rises to a theme.

Hannah Arendt – The Jewish Writings

I might also have suggested Walter Benjamin’s Jewish writings, but the political and philosophical engagements with which Arendt treated her own and others’ experiences of the most dramatic chapters of modern Jewish history, and the way in which she both sparked and responded to the controversy that public Jewish intellectuals invariably provoke when they reflect back on themselves, reveals how critical it is to investigate the Jewish position in history and society — not only for Jews, but as the recent revival of interest in Arendt’s writings on totalitarianism imply, critical for all.

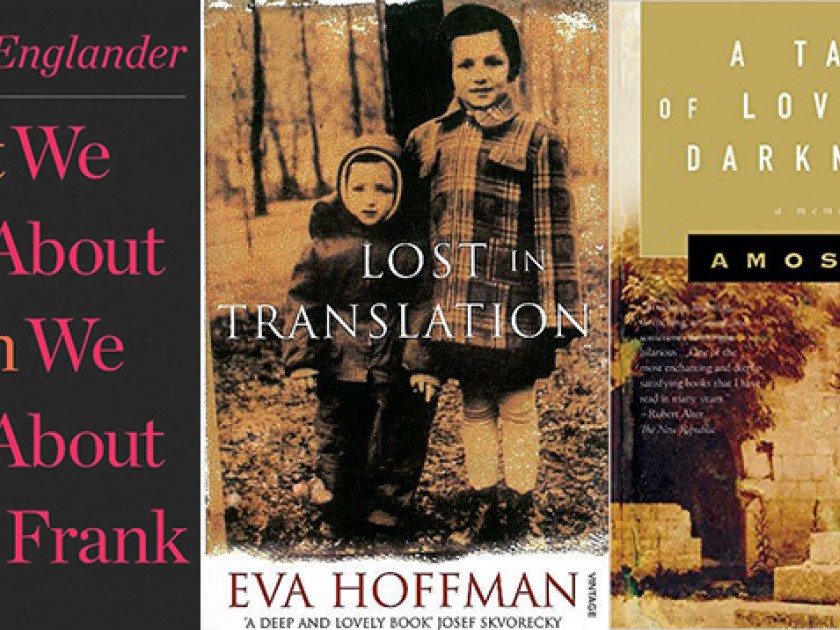

Eva Hoffman – Lost in Translation

While there are many wonderful memoirs of Jewish emigration from the end of the 19th century up to the end of the twentieth, Hoffman’s searingly honest, affecting and psychologically perspicacious account of her loss and rediscovery of herself in a new place and a new language has been enthusiastically embraced by all manner of readers&nmashfrom Jews, to people from other immigrant backgrounds, to people who, though not literally displaced, feel themselves to be peculiarly adrift, lost and uprooted in the rapidly changing modern world.

Amos Oz – A Tale of Love and Darkness and/or Sarah Glidden — How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less

Oz’s beautiful memoir, which functions simultaneously as the story of his own life and that of the young state he grew up in, seems to capture every shade of Israeli experience — the love and the darkness, the dream and the nightmare. And because there really is such profound love here, as well as darkness, those who are ordinarily inclined to see only one side of the picture, whichever side that is, may find in this book a means of encountering the thorniest of subjects somewhat differently. While Sarah Glidden’s graphic memoir of her time on a Birthright tour reveals how, behind the propagandistic messages to which she and her fellow travelers were subject, the individuals she meets in Israel are all far more complex and divided than is generally admitted by the spectrum of political positions and opinions with which they tend to get represented.

Nathan Englander – What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank

This short story collection enters boldly into features and temperaments that broadly characterize Jewish life and experiences today. There is a great deal of Jewish self-critique in these stories, but also a sense of the blind alleyways and limitations that circumscribe just about any political, religious or social position, particularly in those cases where identities appear too sure of themselves. This is not a writer who judges others from a sense of his own moral superiority. Rather, his deep immersion in the post-war Jewish psyche and predicaments sees him attempting, in these stories, to find a way through the modern maze — which, in the first case, requires us to comprehend its maziness as clearly as possible.

Edmond Jabès – The Book of Questions, Vol 1.

Jabès’ handling of the Jewish experience brings new meaning to Jews as “people of the book.” For Jabès, Jewish existence and survival is indistinguishable from the condition of textuality. By invoking questions that anticipate neither answers nor resolutions, the binaries that permeate our conventional habits of thought are all deconstructed in this sublime work such that we can no longer draw the dividing line between Jew and non-Jew, between home and exile, between religious and secular, between belief and non-belief, between poetry and prose, between mind and body, between ancient and modern, between life and death.

Devorah Baum is a lecturer in English Literature at the University of Southampton, UK, and affiliate of the Parkes Institute for the Study of Jewish/Non-Jewish Relations. She is the co-director of the documentary feature film The New Man (2016) and the author of Feeling Jewish (a Book for Just About Anyone), published by Yale University Press.