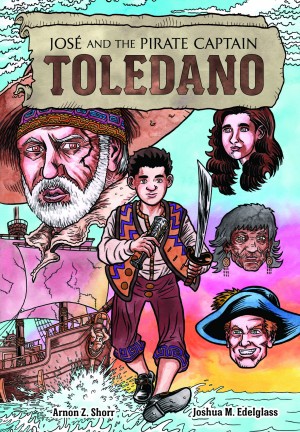

Jews who chose to remain in Spain and Portugal after the fifteenth-century edicts of expulsion faced two choices: they could convert and live as Christians, or they could become members of the Church but secretly practice Judaism. The second path was more dangerous, but even Jews who completely denied their faith were subject to racially based antisemitism. In Arnon Z. Shorr and Joshua M. Edelglass’s graphic novel, a young boy and his father living in the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo try to steer a careful path between allegiance to the Crown and fidelity to their religion. As fast-paced and exciting as any pirate tale, José and the Pirate Captain Toledano also explores difficult questions of identity, family, and becoming an adult under arduous circumstances.

Some conversos (Jews who had converted to Catholicism) tried to escape prejudice in the New World, but the Inquisition pursued them there, as well. José Alfaro’s father believes that his position as treasurer will make him indispensable. Outwardly loyal to the government he represents, Señor Alfaro educates his son privately but still conceals from him the fact that he is Jew. José resents the lessons, believing that his level of knowledge causes local residents to resent him. José’s rage remains just under the surface, ready to explode if he is provoked. His father’s belief that he can keep his dignity and still preserve his past is rooted in desperation. Both text and pictures starkly present the dilemma of characters caught up in contradictions. As José tries to explain his frustration, his father responds with anger; they represent two generations at odds with one another. Without the missing piece of their Jewish past, how could José make sense of his father’s admonition that “to be holy … is to be different?”

Shorr’s pirate scenes achieve the necessary balance between adventure and character development. Without romanticizing lawlessness, he reveals Captain Toledano’s role as a complex interaction of historical necessity and personal choice. There is tension between those who uphold cruel and unethical norms, and the outsiders who challenge them by substituting an unsanctioned system of values. Jews and other marginalized peoples are forced to consider the consequences of their actions, whether they accept unjust limitations or fight against their oppressors. Gradually, as the story unfolds, José begins to understand why his father had encouraged him to be different, but only within seemingly arbitrary boundaries. The author also considers the specific obstacles confronting women in the character of José’s love interest, Rosa. The novel takes place in 1547, when the native Taino Indians had almost completely disappeared due to conquest and disease, but Shorr includes characters who embody their tragic experience.

Edelglass’s illustrations feature muted colors, exaggerated facial expressions, and consciously chosen sound effects from the comics repertoire (BOOM!, WHOA!, and FWOOSH make appearances.) In between, there are moments of stillness and detailed beauty, such as Captain Toledano holding José’s engraved silver kiddush cup in his gnarled hand as he stares fixedly at everything this ritual object suggests about what Jews have lost. Swashbuckling heroes and antiheroes, Jews, Christians, and Indians, all personify the costs of living in two worlds and struggling to remain free.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.