Warsaw Ghetto footbridge over Chłodna Street viewed to the east, 1942, Image via WikiMedia Commons

In the field of history, we have a class of primary sources called egodocuments, encompassing letters, diaries, memoirs, autobiographies, and testimonies. When analyzing this type of primary sources, historians must ask a variety of very specific questions ( Why did they write this? Who was the intended audience? What was their gender? When were they born? What language was it written in originally? What was their socioeconomic status?) in order to understand the context of the source and therefore, its meaning between the lines and beyond the page.

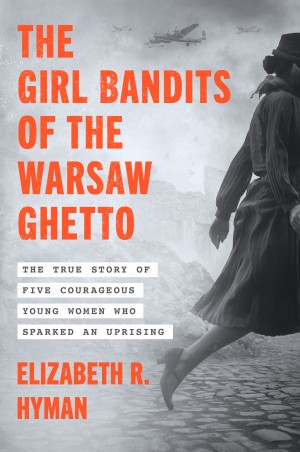

My new book , The Girl Bandits of the Warsaw Ghetto, came about as my emotional and intellectual response to the silences and gaps in Holocaust memory where the experiences of women belong. Of the five women the book follows, three of them — Jewish underground agents and organizers Zivia Lubetkin, Vladka Meed, Dr. Adina Blady-Schweiger — left detailed memoirs, essays, and testimonies. The remaining two women — Tosia Altman and Tema Schneiderman— were murdered by the Nazis in 1943, depriving them of the opportunity to write and reflect on their experiences; the only quasi-egodocuments they left behind were political essays and coded letters, not forms of writing in which they could be unguarded or candid.

This meant that I had to reconstruct Tosia and Tema’s personalities through my understanding of their context in Jewish interwar Poland, and reliance on the writings of others, if I was to present them as full and complete individuals before their lives were cut short.

______

Tema Schneiderman was born in Warsaw in 1917 to a Polish-speaking Jewish family. She studied nursing and worked at a hospital after graduating from a Polish public high school. It was during this period of her life that she met her boyfriend Mordechai Tennenbaum, who brought her into the socialist Zionist Dror movement.

Most of her family was killed in the September 1939 invasion of Poland. During the first years of the war, Tema worked as an underground courier and organizer for the Polish Jewish resistance. On January 11, 1943 she traveled to Warsaw to deliver covert materials to the Jewish Fighting Organization. She sent a telegram to her comrades verifying her arrival in Warsaw and entered the Warsaw Ghetto. She disappeared five days later during an outbreak of fighting known as the “Little Uprising” on January 18, 1943. She was most likely killed in the fighting.

One essay of propaganda authored by Tema survives and is signed with the initials of her Aryan alias, Wanda Majewska.

In a letter recovered after the war, Mordechai Tennenbaum wrote of his late partner: “Over 20 times she crossed borders that separated different parts of Poland…Tema visited every ghetto, knew Jewish life and troubles in every town and city. She was a living treasure of information… She brought messages from the movement to every area…Even Poles and Germans could not reach every part of Poland as she did. And when she came, there was such joy.”

Nearly everyone who wrote of Tema Schneiderman did so in glowing terms, focusing on her beauty and vivacity. However, underground courier Chaika Grossman wrote in her memoir, The Underground Army: “…Tema decided to go into the ghetto. She insisted, and I could not dissuade her. I had barely gotten used to this delicate girl. At first I believed that she was a spoiled child and would not be able to hold out. I don’t know why I always thought her more fit for picking flowers than for the underground. After a few days I was ashamed of these ideas. I realized that she was stubborn, brave and firm in her views. The greater the difficulty, the greater her daring.”

In her memoir They Are Still with Me, courier and arms smuggler Chavka Folman-Raban adds nuance to this portrait of Tema, writing: “For a short while I lived in the same room with Tema …Under the bed was…a suitcase containing pistols and grenades … Tema and I brought the grenades to the ghetto … Each of the girls hid a grenade in her most intimate place, her undergarments. From a suburb of the city we took a streetcar in the direction of the ghetto. I recall our odd behavior during the ride. Tema stood at my side and asked: ‘What would happen if a gentleman invited us to sit beside him?’ We broke into laughter; hiding our fear in this way…” Reflecting on this incident, Chavka wrote: “To this day I see the seriousness of our actions in such a situation and also something of the macabre humor that carried us, spirited young people, through this period.”

From these two excerpts, we can glean that Tema was not simply a lovely young woman and someone’s girlfriend, but a daring, courageous, and stubborn individual in her own right, who possessed strong leadership abilities, and the emotional intelligence needed to understand that to carry out such a mission, one had to blend in — to look like a happy, carefree young woman, not like a frightened, hunted Jew.

______

And then, there’s Tosia Altman.

In her recollections of life in the Vilna Ghetto, underground operative Rushka Korczak wrote the following of her friend and comrade: “Tosia came. It was like a blessing of freedom. Just the information that she came … That we have Tosia visiting us from Warsaw. As if there was no ghetto. As if there were no Germans. As if there was no death around. As if we were not in this terrible war. A beam of love. A beam of light.”

Tosia Altman left us with more writings than did Tema. Born in 1919 in Lipno, Poland, Tosia spoke Hebrew and Polish, and quickly earned a reputation as a talented leader within the socialist Zionist Hashomer Hatzair youth movement. After the German occupation of Poland, Tosia traveled across Occupied Poland on a mission to encourage the young Jews she encountered to engage in clandestine educational and social activities.

We can glean that Tema was not simply a lovely young woman and someone’s girlfriend, but a daring, courageous, and stubborn individual in her own right, who possessed strong leadership abilities, and the emotional intelligence needed to understand that to carry out such a mission, one had to blend in — to look like a happy, carefree young woman, not like a frightened, hunted Jew.

When movement representatives met in Vilna on December 31, 1941, Abba Kovner delivered in Yiddish a famous speech calling for Jewish armed resistance. He then turned to Tosia, and had her deliver the same speech in Hebrew. This speaks to both the deep respect accorded to Tosia specifically, and female operatives generally in the Jewish underground. On July 28 1942, the Jewish Fighting Organization command selected Tosia as one of four representatives to operate on the Aryan side of the city.

On April 18, 1943, the day the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising began, Tosia reported on the action to Commander Yitzhak Zuckerman — who was stationed on the Aryan side of the city — via a factory phone. She continued to relay battle updates to comrades outside the Ghetto over the course of the Uprising, and ultimately escaped the ghetto through the sewers on May 10.

On May 24, 1943 Tosia was hidden in the attic of a celluloid factory with several comrades when the attic caught fire. Some of her contemporaries claimed that Tosia died in the fire; others say that she escaped the burning factory, was handed over to the Gestapo, and then was either tortured to death, or taken to a hospital where the Gestapo interrogated her and left her to die.

Chavka Folman-Raban worked closely with Tosia on a number of occasions, and wrote in her memoir: “She was a few years older than I and more experienced. When I was with her, which was not often, I felt that I was in the presence of a worthy person. Although she radiated authority, our friendship was genuine.”

These recollections, combined with Tosia’s status within the Polish Jewish underground, paint the picture of a stubborn, thoughtful, courageous woman. But complicating this picture is Yitzhak Zuckerman’s own portrayal of Tosia Altman in his memoir, A Surplus of Memory. He includes several less-than-flattering comments about Tosia, though always taking care to point out that these things weren’t his opinions, but that he simply felt obligated to include them. He wrote that Hashomer members didn’t respect Tosia and perhaps found her irritating, and criticized her for entering the ghetto the night before the Uprising when she was supposed to be stationed on the Aryan side.

In one of her final letters, Tosia wrote the following to the movement leadership in Palestine: “I think you’ll agree with me that one shouldn’t draw strength from a poisoned well. I am trying to control myself not to vent the bitterness that has accumulated against you and your friends for having forgotten us so utterly. I blame you that you didn’t help me with a few words at least … Israel [meaning, the Jewish people] is vanishing before my eyes and I wring my hands and I cannot help him. Have you ever tried to smash a wall with your head?”

The majority of this letter constitutes a fairly eloquent, poetic reprimand, but then Tosia ends it with a line tonally out of place with the rest of the letter, to the extent that it sparks laughter. If Tosia was willing to in so informal, casual, and in so darkly humorous a manner, it’s reasonable to deduce that her behavior around other movement members may have been decidedly quirky, or else out of keeping what they considered to be an appropriate demeanor.

______

What emerges from this abbreviated presentation of my analysis of these two extraordinary women is that, while we will never bridge the distance which can only be spanned with egodocumentation, careful reading and comparison between sources can create a blurred, imperfect impression of those who left us with mostly silence.

Elizabeth R. Hyman is the descendant of Polish Jews who fled Europe in 1939 and made their way, as refugees, to the United States. She earned dual master’s degrees in History and Library and Information Science from the University of Maryland-College Park, and has written the history blog, HISTORICITY (was already taken) since 2011. She lives in New Paltz, New York.