Jakob Reimer’s Trawniki identification card photo, taken by the SS. Image courtesy of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Young Peter Black was something of a loner, content to spend long afternoons reading about the movement of armies, the slow, plaintive notes of the Five Satins playing on a suitcase turntable, and a dog-eared copy of The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich sitting on his nightstand. He played wiffle ball in the driveway and pickup football games in a field behind the high school. But it was history that moved him, kept him awake at night next to a stack of Mad magazines and comic books that at times seemed awfully silly, given how war could turn ordinary people into murderers. This was the 1950s, in a quiet neighborhood in the suburbs of Boston.

Peter Black, now retired, dedicated years to the OSI. Image courtesy of U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

One day in middle school, Black decided he would study the history of Nazi Germany. By the time he enrolled at the University of Wisconsin in 1968, Adolf Hitler had been dead for twenty-three years. But to Black, the need to understand the decisions of national leaders bent on mass murder seemed more urgent than ever, considering a world that had stumbled into a nuclear age.

I met Black in the early months of 2017. By then, he had spent his professional career doing exactly what he had vowed to as a teen — and to great success. As a World War II historian, he had been part of a tiny unit deep inside the U.S. Department of Justice that for more than three decades identified and prosecuted Nazi war criminals who slipped into the United States alongside masses of European refugees in the years after the war.

Since 1990, the Office of Special Investigations (OSI) helped denaturalize and deport more than seventy Nazi collaborators — more than all other countries in the world combined, including Germany.

As a veteran investigative reporter, I had spent a decade on staff at The Washington Post. But I knew very little about the Nazi-hunting unit, or the men and women who raced against time to expose and bring to justice war criminals hiding in plain sight in middle-class America — their terrible secrets buried deep.

I came away from that first meeting with Black with two questions. In a country that had sacrificed so much to defeat Hitler and save the Jews of Europe, how was it possible that Hitler’s helpers were living here alongside Holocaust survivors and veterans who had crossed an ocean to free them?

Elizabeth “Barry” White, currently a historian at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, spent years working at the OSI. Image courtesy of U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

And just as intriguing: How did Black and his colleagues manage to probe some of the war’s darkest moments, day after day, year after year, and then free themselves from that darkness when they went home at night, when it came time to have dinner with a spouse, rock a newborn, coach a soccer game, take an anniversary trip?

By the time I finished writing Citizen 865: The Hunt for Hitler’s Hidden Soldiers in America, I discovered the story was not just about darkness but also about light, the pursuit of truth by Black and a team of American Nazi hunters who believed that justice — even delayed — is more critical than ever in a world that too often finds itself in the exact same place, confronted by bigotry, hate, mass murder.

Citizen 865 is focused on a lesser-known investigation carried out by the OSI: the hunt for the men of Trawniki. In 1990, in a dusty basement archive in Prague, Black and OSI historian Elizabeth “Barry” White discovered a Nazi roster from 1945 that no Western investigator had ever seen. The long-forgotten document, containing more than 700 names, helped unravel the details behind a lethal killing force that had helped the SS murder 1.7 million Jews in fewer than 20 months, the span of two Polish summers. Early in the war, the men had trained at a camp in the Polish village of Trawniki.

It was, in every sense, an SS school for mass murder.

Over many months, I essentially retraced the steps of Black and the OSI team. I traveled to Trawniki, Prague, Warsaw, Lublin and Vienna, pored over war records and court transcripts and studied the oral histories of Holocaust witnesses and survivors. Some had settled in the United States after the war only to learn that the so-called “Trawniki men” had followed — and gone on to become naturalized citizens.

The OSI team pursued these men, and, up against the forces of time and political opposition, battled to the present day to remove them from US soil.

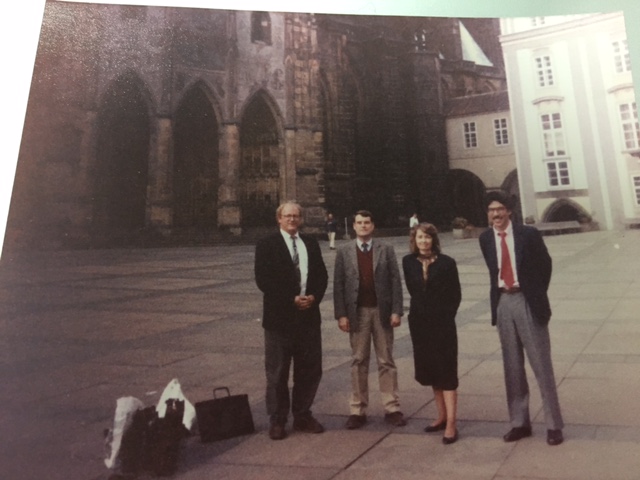

Peter, Barry, and two other historians in Prague in 1990. Image courtesy of Barry White.

Even after Black went on to work at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, he continued to work on Trawniki cases. Over time, he helped identify more than 5,000 members of the killing force, becoming the world’s foremost expert on the camp and its recruits.

“If legal consequences for mass murder and mass atrocity become habitual to political and judicial behavior in the twenty-first century,” Black said after his retirement, “perhaps we can prevent mass murder in the future.”

I found hope in Black’s words and in the steadfast work of a determined team of historians and prosecutors who refused to look away.

Debbie Cenziper is an investigative journalist, professor, and author based in Washington, D.C. A contributing reporter for the investigative team at The Washington Post, she has won many major awards in print journalism, including the 2007 Pulitzer Prize. Cenziper is the co-author of the critically acclaimed Love Wins: The Lovers and Lawyers Who Fought the Landmark Case for Marriage Equality. She was recently named the director of investigative journalism at the Northwestern University Medill School of Journalism.