Acts of violent antisemitism have plagued Jews for millennia, but only during World War II did hatred reach such vehemence as to target and imperil all Jewish children. What do young people today know about children and babies being thrown into the gas chambers alongside the adults? The Claims Conference, an international non-profit organization that secures compensation on behalf of survivors, recently conducted two studies on awareness of the Holocaust amongst young adults. The first study occurred in 2020 in the US; the second study took place earlier this year in several European countries. Both reports demonstrate that millennials and Generation Z in America and Europe know almost nothing about the Holocaust. In perhaps one of the most disturbing revelations of this survey, 11%of US millennial and Generation Z respondents believe Jews were the perpetrators of all the atrocities committed during World War II.

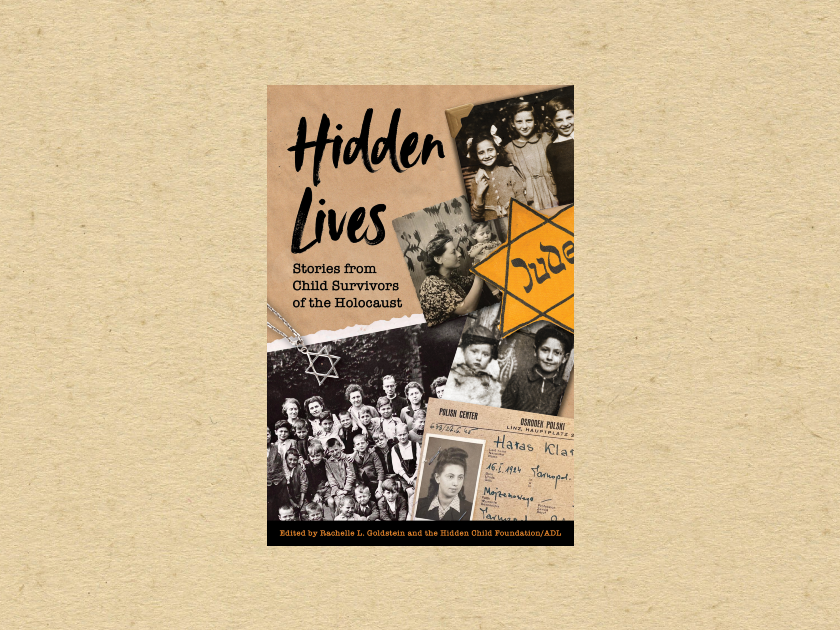

How have facts become so distorted in the minds of so many people, even as we survivors are still alive to tell our tales? And where is the repudiation of this falsification of history? Apparently not in our schools. The lack of education about the Holocaust and the findings of this report make clear the continued need for survivors to document their experiences in books. Coming out this November from Second Story Press is Hidden Lives: Stories from Child Survivors of the Holocaust, which I edited.

As memories continue to fade, we — the last and youngest survivors of the Holocaust — must remind everyone, everywhere, that 1.5 million Jewish children (from infants to older teens) were murdered because of their parents’ or grandparents’ religion. By war’s end, only 6 to 11% of Europe’s Jewish children had survived, versus 33% of the adults. Yes, nine out of every ten Jewish children were killed. Yet, now, this cataclysm is being distorted — or worse — refuted.

For many years, we, too, tried to forget our wartime experiences. By 1945, 80% of the child survivors were orphaned. Most had suffered the heartbreak of separation from parents and multiple displacements, along with the other trials of war, including fear, hunger, pain, illness, and bombings. At war’s end, we felt a strong need to put these searing recollections behind us and go on with our lives. And for the most part, we succeeded.

Being given a second chance to live certainly increased our motivation to achieve. Jakub Gutenbaum, the former leader of the Child Survivor group in Poland, writes in Hidden Lives, “These children were already so grown-up and knew what they wanted — to study, to catch up for the lost years.” He quotes Maria Falkowska, the postwar director of The Children’s House, a Jewish orphanage in Helenowku, Lodz: “The most startling characteristic of this group was their thirst for knowledge. They studied late into the night and, even in the worst snowstorms, when they had to trudge many kilometers to the nearest tramway and would not return till dark, it was impossible to keep them home, away from their goal.”

We — some of the last witnesses to this period of terror — now bring our stories to today’s readers (high-schoolers and adults) and to future generations.

Yet, revealing our identity or our background remained difficult. In her story in the collection, Renée Roth-Hano writes, “The isolation — the alienation, really — continued in postwar France. For a long time, I couldn’t look into people’s eyes lest they’d find out I was Jewish. Even when I felt safe enough to bring up my Jewish background, I would clam up, my throat choking out the words.”

For decades, we were encouraged to “get over it.” Our voices were suppressed, either by our own volition or that of our elders. Our silence became our way of coping with the incomprehensible. As Doctor Robert Krell states in his introduction to Hidden Lives, “Silence served us well while hiding in Christian homes, in convents, in caves, in partisan groups, even in concentration camps. Survival so often depended on not being noticed, being inconspicuous; on the ability to suppress tears, ignore pain. Grief was borne in silence; so was rage.”

Rage was inevitable and reached a climax in the late 1980s as we found one another. A renewed focus on our childhood had been sparked by the documentary As If It Were Yesterday, written and directed by Myriam Abramowicz and Esther Hoffenberg. The film told the story of the Jewish Belgian Resistance Network, a group that saved more than 4,000 children during the war. Nicole David, a child survivor of the Holocaust, saw the film at the time and was so moved that she contacted Myriam Abramowicz. During their conversation, Myriam mentioned that every time the film was shown, people who had been hidden as children during the Holocaust came to her with the same remark: they felt they had lost their childhood and grown up too soon.

Inspired by the film, Nicole planned a gathering of hidden children with the support of the Anti-Defamation League’s director, Abraham Foxman, a child survivor of the Holocaust himself. And so in 1991, with more than 1,600 people from twenty-eight countries packed into a Manhattan hotel, the Hidden Child Foundation/ADL was founded. And hidden children were finally given validation that they, too, were survivors of the Holocaust; only then did many of us attempt to deal with our demons.

We — some of the last witnesses to this period of terror — now bring our stories to today’s readers (high-schoolers and adults) and to future generations. All these accounts were initially published by the Hidden Child Foundation/ADL, first through annual hard-copy newsletters, and since 2020 through email communications. Hidden Lives: Stories from Child Survivors of the Holocaust is a collection of some of these powerful accounts. Our aim is to inform everyone about the threats of antisemitism and similar hatreds.

After decades of silence, we are dedicated to remembrance and commemoration.

Hidden Lives: Stories from Child Survivors of the Holocaust by Rachelle L. Goldstein

Rachelle L. Goldstein was born to Jewish parents in Brussels, Belgium just before the onset of WWII. She was hidden from the Nazis as a young child in order to save her life. Rachelle is the Co-Director of the Hidden Child Foundation/ADL, based in New York.