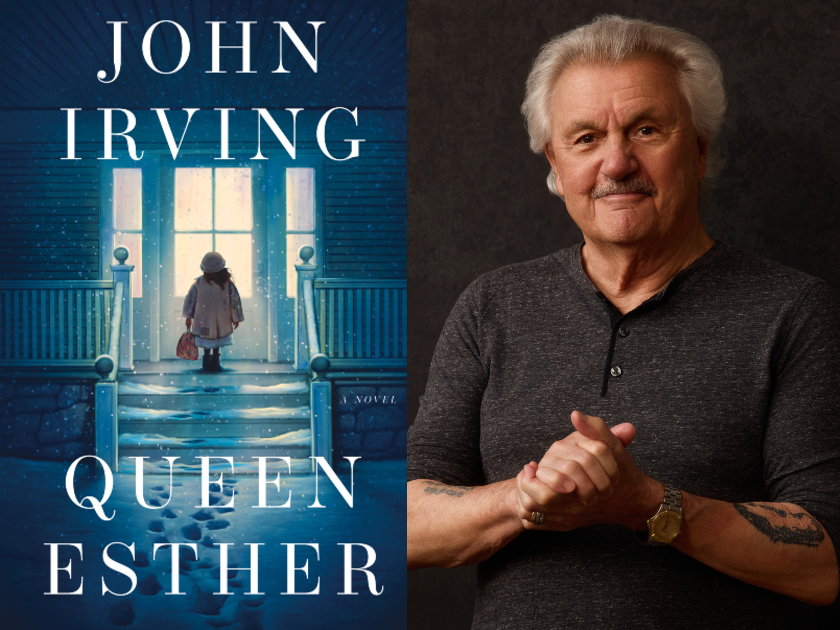

Author photo by Katherine Holland

In his new historical novel, Queen Esther, acclaimed author John Irving returns to the New England setting of St. Cloud’s Orphanage from his 1999 novel The Cider House Rules. Readers of Irving’s previous work will find familiar characters as well as new ones: the Winslow family and Esther Nacht.

Esther is a force of nature. A Jewish orphan who grows up at St. Cloud’s, she is adopted at fourteen years old to be a nanny for Honor, the youngest Winslow daughter. When Esther was a child, her family fled Vienna to escape antisemitism, and her mother was subsequently murdered by antisemites in the United States. In the Winslow family, Esther finds a safe, nourishing haven; and in Honor, she finds a lifelong confidant and coconspirator. The two make a pact: when the time is right, Esther will have a child and Honor will raise it.

When Esther’s biological son, Jimmy Winslow, is in college, he chooses to study abroad in Esther’s native city. In Vienna, he discovers more about how families can be constructed and protection offered to those who need it.

Simona Zaretsky: How did Esther Nacht come to be the driving force of your new novel? And what was it like to return to the setting of The Cider House Rules?

John Irving: I purposely chose a Jewish orphan — one who is old enough to know her name and the story of Queen Esther, her namesake. I already knew my fictional orphanage in Maine, and how empathetic Dr. Larch, the orphanage physician, is. Esther Nacht is born in Vienna in 1905; her life is shaped by antisemitism. Esther is not yet four when she’s abandoned at the orphanage in St. Cloud’s — far from her home and everyone she ever knew. I was an American student in Vienna, in 1963 – 64, when my Jewish roommate opened my eyes to antisemitism. Later — whenever he called me, or I called him — he always said, “In Wien kann man keinen Spaß haben.” (“In Vienna, you can’t have fun.”) Both when I was in Israel in 1981, when my former roommate was alive — and when I was back in Jerusalem in 2024, after he’d died — he was always on my mind. With my orphaned Esther Nacht, I wanted to create a young adult who would fervently need to reconstruct her Jewishness. By the time she’s a teenager, Esther is driven to make up for the Jewish childhood she was denied. And what does Dr. Larch impart as a creed to the orphans in his care? “You have to be of use,” Larch instructs them. My Esther feels that she is born to be of use.

SZ: How do you see this orphan Esther in conversation with the Queen Esther of Jewish tradition?

JI: Esther’s parents want to escape the antisemitism they sense is rising in Europe. Her father dies on the voyage from Bremerhaven to Portland; her mother is murdered by antisemites in Maine. Esther has every reason to believe there’s no escaping antisemitism. It is integral to Esther’s Jewish identity that she believes her role as a good nanny is a lifelong obligation. And why wouldn’t she believe that protecting the Winslow she gave birth to is her job? And why wouldn’t my Esther, like the biblical Queen Esther, dedicate her life to protecting other Jews?

SZ: As you point out, Esther’s Jewishness shapes her life and her decision-making in large and small ways. By contrast, her biological son, Jimmy, is brought up by Honor as a non-Jew. He is constantly grappling with his sense of self and with questions of whether or how to be Jewish. What is the significance of these characters’ different relationships to Jewish identity?

JI: Jimmy’s birth mother, Esther, has a host of good reasons to actively participate in the Zionist cause. And a big part of Esther’s commitment to protecting the Winslows is her not allowing Jimmy to be Jewish. As Esther knows firsthand, it’s not safe to be Jewish.

Being a writer is also a factor of Jimmy’s alienation. Writers are alienated; they’re outsiders, more often observers than participants.

SZ: Throughout the book, Esther never has a permanent address. Instead, letters are sent to her in care of a succession of different people in both Europe and in Israel. How do you see the impermanence of residence, her lack of a physical home in many ways, at play? Does her wandering and self-imposed exile influence Jimmy?

JI: I wanted my Esther to share the biblical Esther’s need to hide her Jewish identity and the biblical Esther’s way of revealing herself on her own terms. Esther’s “impermanence of residence” — her “self-imposed exile,” as you put it — reflects the centuries of exile and murder her Jewish ancestors suffered. Jimmy’s restless wandering mirrors his birth mother’s early life in exile.

Jimmy is an exaggeration of myself as a younger man. Both in Vienna in the sixties, and in Jerusalem in the eighties, Jimmy is even more unaware than I was. Jimmy Winslow is my POV character. He’s an ally of Israel and the Jews, but he’s not raised as a Jew. It matters to me to see Israel and Jewishness from Jimmy’s point of view. I believe that Israel and the Jews need allies who aren’t Jewish.

SZ: The Winslows are a non-traditional family, especially for the conservative town of Pennacook. The value they place on their daughters’ and nannies’ intellectual stimulation is at odds with Frau Holzinger’s belief that, as her daughter says, only “fathers are the ones who have tools.’” Why did you highlight this contrast?

JI: Families interest me — especially families that are missing someone, or lacking something. An absent father, a lost child; maybe there is a missing uncle everyone is afraid of, and everyone hopes he never comes back. Given the good family Jimmy comes from, I wanted him to live with a broken one — the Holzingers — in Vienna. I imagined Jimmy watching movies with the antisemitic Irmgard Holzinger before Irmgard’s working hours as a prostitute begin. I knew I would reconnect Jimmy with Irmgard’s son, Siegfried, in Jerusalem — where Fräulein Eissler, who adopts Siegfried, takes him. Siegfried’s new family is Israeli. There’s an intentional contrast here. Esther’s intention is to keep Jimmy safe by not allowing him to be Jewish; Fräulein Eissler saves Siegfried by making him a Jew. Both Esther and Fräulein Eissler are right.

Like the biblical Queen Esther, I wanted my Esther Nacht to be a miracle of hiddenness and revelation.

SZ: The year Jimmy spends studying abroad in Vienna, the city where his mother was born, is vividly described; I was struck by how close the city and its inhabitants are to World War II. KGB and Mossad agents operate in the shadows of the houses and streets where the students cavort. Could you speak about this colliding of past and present political memories?

JI: Like Jimmy, I lived in Vienna as a student, and it’s a city I’ve written about before. My first novel, Setting Free the Bears (1968), was historical fiction, set in Vienna at the time of the Anschluß, and in post-war Vienna. It was optioned for a film by Columbia Pictures (UK), and Irvin Kershner was assigned as the director. Kershner’s first task was teaching me how to write a screenplay. We spent almost three years working in Vienna — some of it in the Vienna War Archives, searching for what we could use to document the Nazis’ rise to power. The film was never made, but Kershner was a good teacher. A Russian Jew whose family immigrated to the US long before the war, Kershner is best known as the director of The Empire Strikes Back—to me, the best of the Star Wars movies. During my time with Kershner in Vienna, my son Brendan was born, and I had time to reflect on what you call “the shadow of KGB and Mossad operatives.” In my student days, I knew two of each. They’ve long since vanished; they were not much inclined to communicate with me. You’re right, “this colliding of past and present political memories” is omnipresent in Vienna.

SZ: Both Esther and Jimmy have favorite books that give them solace and inspiration. Why, for you, was it important to include these literary references?

JI: The novels that Esther and Jimmy love are ones that satisfy their self-searching. Esther, reading Charlotte Brontë, wants to get a tattoo of a quote from Jane Eyre about self-respect. Jimmy, reading Great Expectations, imagines himself as a Dickensian hero.

SZ: The Winslow family, namely Constance and Thomas, try to act as ambassadors to bridge the tension between the townsfolk of Pennacook and the private Pennacook Academy, where Thomas is an English teacher. How is the town shaped by these dynamics?

JI: The tensions between town and gown are as old as the Middle Ages; academic gowns and hoods are medieval. The civil rights movement and the Vietnam War sparked protests of a town and gown nature in 1970. Think of the shootings at Kent State University in Ohio, and at Jackson State University in Mississippi. In Exeter, New Hampshire, I grew up as a townie and a faculty brat in a small mill town with an internationally prestigious private school — Phillips Exeter Academy. Exeter appears in many of my novels — with names as various as Exeter, Gravesend, and Pennacook. But it’s always Exeter.

SZ: The conception of Jimmy, his childhood, and his coming of age during his study abroad year in Vienna in the mid-1960s are such a large focus of the book. Esther is not physically there for any of this; instead, she saturates the background of the story. How did this narrative style evolve?

JI: In those Vienna chapters, you’re right — “Esther is not physically there,” but (consistent with the Mossad operative that she is) Esther is directing Fräulein Eissler. Esther is operating behind the scenes. Again, like the biblical Queen Esther, I wanted my Esther Nacht to be a miracle of hiddenness and revelation. This novel ends in 1981 — the year I was invited to visit Israel by the Jerusalem International Book Fair and my Israeli publisher. I accepted the invitation at the urging of my favorite European publishers; they were Jewish, with longstanding ties to Israel. They were leftist, nonobservant Jews who criticized the right-wing, Likud government of Menachem Begin for accelerating the settlements in the West Bank. They thought the Jewish presence there, and in the Gaza strip, might make Palestinian self-determination harder to achieve — they worried that a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict could slip away. A historical novel foreshadows the future. In April 1981, the seeds were sown for an eternal conflict. In July 2024, when I went back to Jerusalem, to refresh my memory of the visual details — going everywhere I’d gone forty-three years ago — the war in Gaza was ongoing. In the evenings, I was alone; my Israeli friends were at anti-Netanyahu protests.

SZ: Film and music suffuse Jimmy’s time in Vienna. They bring the bright texture of this era to life, and offer Jewish cultural glimpses. Could you speak about weaving these songs and films in? They act, at times, as points of reference when Jimmy doesn’t know the language and he uses them as tools for translation and common touchpoints.

JI: In the last chapter, set in Jerusalem in 1981, the dialogue mirrors what was said to me, or what I overheard. In a historical novel, the dialogue must also be what was commonly said in that time and place. In the Vienna chapters, in 1963 – 64, I’m especially fond of Irmgard’s and Jimmy’s dialogue about Fred Zinnemann — a Polish Jew who grew up in Vienna and had a law degree from the University of Vienna. Fred Zinnemann was later the director of High Noon and From Here to Eternity. Zinnemann’s parents — this was after the Anschluß — returned to Poland, where they were murdered by the Germans in the Holocaust. These are “Jewish cultural glimpses,” as you say, and — in my mind — music and songs go together. Writing screenplays has helped me as a novelist — most of all with dialogue, but writing screenplays has also taught me to use films and songs as points of reference in a historical novel.

SZ: Do you see Queen Esther as having any overarching morals?

JI: Yes. They’re summed up in the epigraph to the novel, which is from the Book of Esther in the Bible: “For we are sold, I and my people, to be destroyed, to be slain, and to perish.”

Queen Esther by John Irving

Simona is the Jewish Book Council’s managing editor of digital content and marketing. She graduated from Sarah Lawrence College with a concentration in English and History and studied abroad in India and England. Prior to the JBC she worked at Oxford University Press. Her writing has been featured in Lilith, The Normal School, Digging through the Fat, and other publications. She holds an MFA in fiction from The New School.